With Pop-Star Flair, Violinist Aisslinn Nosky Embarks on a Mozart Concerto Cycle with H&H

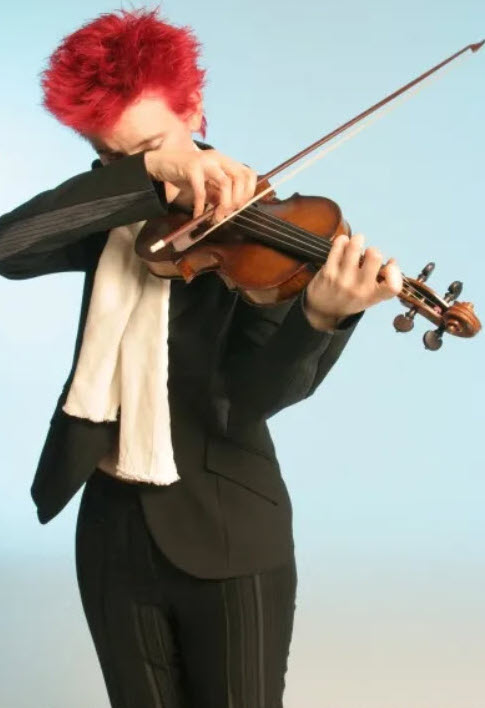

Violinist Aisslinn Nosky’s performances are unmistakable. And her look is just as thrilling as her musicality.

Donning a bright blue jacket to offset her pixie-cut red hair, she took listeners on a vivid musical tour through Vivaldi’s Four Seasons as part of the Handel and Haydn Society’s season opening concert at Boston’s Symphony Hall this past October. Nosky played the dual roles of concertmaster and soloist, tossing off the florid runs that course through these works with fiery intensity. Humor was very much part of this reading. She rendered the drunken song in Autumn while yawning and pretending to doze off. She shaped other sections in wide lyrical arcs, with her greatest technical powers reserved for Winter and Summer, each crafted with dazzling precision.

Performing these works as a cycle is yeoman’s work, even if there appears to be no historical precedent to do so. “I don’t believe Vivaldi intended the Four Seasons to be performed all at once as a cycle,” says Nosky, reached at her home in New York. “So I’m not being historical in that sense. But I like doing it.”

The wide-ranging keys of each Season make it difficult to string them together without creating fitful contrasts. Yet Nosky brought a unifying element by writing and performing her own cadenzas to link each concerto with the next. “I heard some Italian violinists do bridges between each [of them], and so I decided years ago when I had the opportunity to do all of them myself that I would make my own little cadenzas,” Nosky says. “And really what I do is try to change the energy of the end of one concerto and get into the next concerto’s energy.”

The process of performing these works together, she admits, can be tiring. “For most violinists, it’s mostly exhausting to play all four,” she says. “It exhausts me, anyway.

“I think when they’re strung together it makes it even more exciting an experience for the audience and for the players,” Nosky adds. “I’ve performed them with stopping in between. And so each concerto would get a little round of applause. And it’s perfectly fine. But I think there’s something extra exciting when everybody has to wait in order to build up the excitement.”

At 43, Nosky has shown vitality across her career. For her latest high-profile project, a complete Mozart violin concerto cycle, she traveled through rarely performed Haydn—an unusual journey for most violinists, but in perfect keeping with the H&H approach.

Born outside of Vancouver, she made her solo debut with the CBC Vancouver Orchestra at age 8. She attended the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, hoping for a career as a quartet musician.

She has performed with string quartets as well as with leading period-instrument orchestras as both leader and soloist. She was a member of Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra from 2005 to 2016, and was a founding member of the Eybler Quartet, exploring the string quartet literature on period instruments. In addition to her work with H&H, Nosky served as principal guest conductor of the Niagara Symphony from 2016 to 2019.

Striking a balance between personal taste and adherence to musical tradition has long been one of her goals. “Everybody loves Aisslinn’s flair, the dynamism on stage,” H&H conductor Harry Christophers says. “But I don’t think people realize also just how much she is part of the music she’s playing. Just leading the orchestra, she’s at one with that, she’s conscious of everything that’s going on around her.”

As concertmaster, Nosky has a rare knack for revealing the multiple layers of a Bach concerto grosso as well as a Beethoven symphony. “She leads by example,” says Renée Hemsing, a violinist and violist with H&H. “She plays with a rhythmic reliability, and knows the multiple roles on stage at any given time—the foreground/background, connective tissue, motor rhythm, protagonist/antagonist—and plays accordingly, so that others can follow her example. She provides a compass for the ensemble.”

As concertmaster, Nosky has a rare knack for revealing the multiple layers of a Bach concerto grosso as well as a Beethoven symphony. “She leads by example,” says Renée Hemsing, a violinist and violist with H&H. “She plays with a rhythmic reliability, and knows the multiple roles on stage at any given time—the foreground/background, connective tissue, motor rhythm, protagonist/antagonist—and plays accordingly, so that others can follow her example. She provides a compass for the ensemble.”

Nosky was drawn to early music when she discovered Tafelmusik while in school in Toronto. “I was just completely fascinated by what they were doing,” Nosky recalls. “It seemed very different to me than the music-making I had seen up to that point. I mean, they just seemed to be having so much fun, you know? The fun that I perceived coming off the stage really intrigued me.”

Nosky enrolled in a course on performance practice, taught by Tafelmusik director Jeanne Lamon. Her path, it seemed, had been set.

“I think there’s no aspect of my music-making that’s not affected by principles of historically informed performance,” Nosky says. “I’m always trying to consider the composer’s intentions, what they might have been.

“Of course, one thing I always keep in mind is that I really have no idea. I will never know. I may be completely wrong. The composer could walk into the room, magically brought back to life, and hear me playing one of their concertos and say, ‘I can’t believe it sounds like…that. Everything you’re doing is not what I wanted!’”

“She leads by example,” said Renee Hemsing, violinist and violist with H&H. “She plays with a rhythmic reliability and sensibility. She knows the multiple roles on stage at any given time — the foreground, background, connective tissue, motor rhythm, protagonist, antagonist, etc. — and plays accordingly, so that others can follow her example, providing a compass for the ensemble.”

Nosky is pointing to a central dilemma of her field. Historically informed performance has long brought up controversial notions of authenticity, which has been derided by various critics as a modernist aesthetic. In 2001, HIP conductor and scholar John Butt contextualized that very criticism. In revivals of early music, he wrote in New Grove, “adherence to details that are assumed to be historically precise and unambiguous rarely serve to cover the radical differences between the present and various pre-modern ages.” So-called authentic performances are, in his view, more of a postmodern phenomenon.

Nosky sees it as another element of risk. “Taking that chance is exciting to me,” she confirms. “I think it’s one reason why violinists can play the same music and have it come out completely differently. Because they are different people, different personalities, from different modes of research, different ideas about what [composers] might have intended.”

Nosky has taken such a personal approach to her recordings of Haydn’s violin concertos with H&H. Haydn composed these works in the 1760s during the first decade of his employment at Eszterházy. Nosky’s performance of Haydn’s 1769 Violin Concerto in G, played as part of an all-Haydn concert in 2013, was acclaimed by the Boston critics.

Jonathan Blumhofer of the Arts Fuse wrote that Nosky “proved a probing interpreter of this concerto, shaping the solo part with grace, color, and energy. Her colleagues in the orchestra followed her every step, wholeheartedly capturing the music’s charms, occasional quirkiness, and humor.”

Yet for all of Nosky’s zest, the works do not yet reveal the composer’s mature style. “They are from quite early in Haydn’s compositional career,” Nosky explains. “And I don’t think that they necessarily explore too many emotional complexities. Like there’s nothing wrong or incorrect about these pieces, but they indicate where he is going to go as a composer.”

Pointedly, Christophers, who conducted these recordings, disagrees. He feels Haydn showcases the best qualities of Nosky and the ensemble that accompanies her. “If somebody benefits from the period-instrument movement, for me, it’s Haydn,” Christophers says. “Until I came to H&H, I’d never performed Haydn with a period orchestra. I did quite a bit of Haydn with the BBC Philharmonic. And I remember the leader of the BBC Phil saying to me, ‘Harry, you should be doing Haydn simply every month just for discipline, because it’s so hard.’”

Difficulties aside, H&H’s recordings nonetheless highlight the dramatic power and sparkling wit that the composer is known for. “Aisslinn works very, very hard with the strings, making sure we get lots of vitality and character and clarity and energy,” the conductor adds.

“Haydn was meticulous, sometimes too meticulous,” Christophers continues. “And sometimes you get this ‘He did it here, does he mean it there?’ And, of course, you have to make judgements. We’re doing everything that Haydn says, and the ideas he gives us on the page. But then we’re also adding our own spin. That’s great fun to play with and it just allows when we’re performing them to put that imagery to life.”

For Mozart, ‘Let’s take risks, have fun’

That is a tall order for concertos, like Haydn’s, that are not often performed. But the success of these recordings led Nosky to tackle more celebrated repertoire—Mozart’s violin concertos, which she is in the process of performing and recording with H&H.

“I think [Mozart’s concertos] are already the work of a mature composer, who goes different places and of course keeps developing throughout his too-short life,” Nosky says. “But they’re crafted so expertly. There are no notes out of place.”

Written before he turned twenty, Mozart’s five violin concertos sparkle with a mature melodic grace as well as technical flair, a combination Nosky finds particularly attractive. “I think that that issue has made me focus on the character, the mood, and the fun that I think Mozart infused into these concertos,” Nosky says. “We don’t know, but I believe he wrote them to play himself.

“Since the beginning of this recording project, I’ve been keenly aware that these pieces have been recorded wonderfully, many times, by many great artists over the years. To be honest, that’s a little bit intimidating. I have been trying to figure out what I can say with my violin about these pieces that hasn’t already been said.”

Indeed, Nosky achieves a unique sound in these works by drawing out the feeling of live performance. “What I’ve tried to focus on is, how we can bring the energy that’s in the room, the energy that’s flowing between the audience and the orchestra, how we can really have that sound like it’s a live concert on a recording?” Nosky says. “So I thought let’s bring our own vision. Let’s take risks, let’s have fun.

Indeed, Nosky achieves a unique sound in these works by drawing out the feeling of live performance. “What I’ve tried to focus on is, how we can bring the energy that’s in the room, the energy that’s flowing between the audience and the orchestra, how we can really have that sound like it’s a live concert on a recording?” Nosky says. “So I thought let’s bring our own vision. Let’s take risks, let’s have fun.

“In my case, I like to make people laugh,” Nosky continues. “And I try to do it with my violin when it’s appropriate. I believe Mozart put some potential comedic moments in these concertos. A very obvious example might be that I would take a moment—take a pause in the music, take a breath—and have the orchestra wait for me. And I might do that with a different timing every single time. So that, together and collectively, we take this as a moment. And if it works, and it’s perfectly together as an ensemble, it can be humorous.”

Such was the case with her performance of Mozart’s First Violin Concerto with H&H in Boston’s Symphony Hall this past January. Her reading found both dramatic urgency and dance-like grace.

The opening movement coursed urgently, though Nosky was a warm and lyrical presence when her solo entered the fray. Even this early concerto offers technical fireworks. Nosky tossed off the winding arpeggios and running scales with balletic ease. A shift to the minor key introduced sudden darkness. Nosky’s cadenza, a play on the opening theme, brought the movement to a joyous conclusion.

Simple falling figures, which characterized her entrance in the second movement, flowered into long lines. Nosky’s tone throughout found every degree of light and shade. It was always singing.

The finale moved with furious intensity, and Nosky delivered her solo passages with soulful conviction. Mozart’s music, she revealed, provides the vehicle for almost rock-star flair.

And Mozart, Haydn, and Vivaldi, Nosky reminds us, were the rock stars of their day. “They were there to have a good time,” Nosky says. “They liked a good performance. Mozart loved to dance, and he used to sneak out all the time to parties.”

Does Nosky join in such sneaky fun, in the interest of historical performance research? Nah, she laughs. “I don’t do that, I just practice all the time.”

Performing this music, Nosky and H&H deliver an almost physical approach to the repertoire. “When I first came to H&H, I saw very much the orchestra sort of being static,” Christophers recalls. “And particularly for me since I feel that most of Baroque and Classical music is based on dance, originally, with the energy that comes through it.”

“Aisslinn and I talk a lot about gestures,” he continues. “So if you see a staccato or a wedge on a note, it’s not necessarily the same each time. It’s a gesture according to the mood we are trying to create in the music.”

Much of that mood is only enhanced by Nosky’s own glam appearance. “I understand that the way I appear might be striking to some people,” she says. “And I certainly don’t do it to try to detract in any way from the performing of the music. I strive to be, as a performer, a hundred percent genuine. Because I believe that makes the music sound better.”

“To me,” adds Nosky, “when a performer is perfectly at home with themselves, and genuine in their delivery of the performance, there’s nothing more beautiful in the world.”

Aaron Keebaugh has written for The Musical Times, Corymbus, and The Classical Review, for which he serves as regular Boston critic. A musicologist, he teaches at North Shore Community College in Danvers, MA.