Tina Chancey and Hesperus use 100-year-old movies to present 500-year-old music to 21st-century audiences

Up on the movie screen, Douglas Fairbanks slips unobserved into a rough cantina (setting: California, a long time ago). It’s The Mark of Zorro, the 1920 silent feature that made Fairbanks—he of the dazzling smile and devil-may-care spirit—one of Hollywood’s first action superstars. Zorro reveals himself as the Masked Avenger and takes on the bad guy with amazing stunts and dazzling swordsmanship.

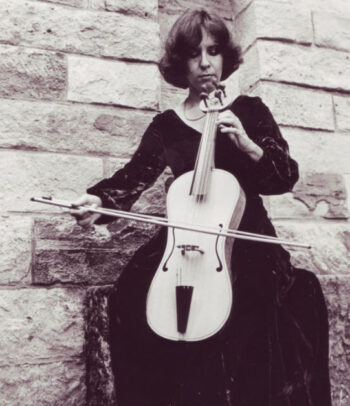

Below the screen, the musicians of Hesperus are doing some swashbuckling of their own. They start low and slow, with Hesperus founder and director Tina Chancey on Renaissance violin picking out the first 8-bar phrase of Diego Ortiz’s “Recercada Segunda,” a jaunty set of improvisations over the passamezzo moderno groundbass from his Trattado de Glosas of 1553.

As Zorro slashes a trademark “Z” into his opponent’s haunches and romps over barroom furniture, the musicians ratchet up their energy, adding countermelodies and leaning hard into cross-rhythms. When Zorro leaps onto the mantelpiece and cries out “Justice for all! Punishment for the oppressors!”—his words on a title card—the players hit it, too. Old, older, and fresh-as-the-moment music come together to close the scene.

The Hesperus Signature

Tina Chancey and Hesperus have developed 12 silent movie soundtracks over the past two decades, among them swords-and-tights action films like Zorro, Robin Hood (1922) and The Three Musketeers (1921) and horror like the Lon Chaney Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922)—all of them classics and all set in the kind of bygone times that just cry out for early music. Hesperus scores its soundtracks with historic music performed by period-performance experts on period instruments.

By now, the soundtracks have become Hesperus’ signature. The group has recorded them, traveled them to early-music festivals and art-house theaters, and toured them all over, from the august American Film Institute Silver Theatre in Maryland to a memorable engagement in Wyoming where, in a hat-tip to historical silent-film performance, the celluloid film stock started to burn, and the players had to vamp while repairs were made. Robin Hood alone has had at least 25 outings over the years.

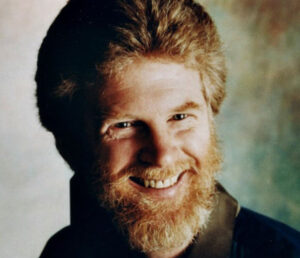

You have to admit, though, it’s not your standard early-music concert fare. It is not, perhaps, dignified, what with the vampires and the Men in Tights. It is not, perhaps, what you might expect from one of American early music’s eminent and long-established organizations. Founded by Chancey and her husband, the late Scott Reiss, in 1979—both barely in their 20s—Hesperus has over the years carried out international tours under the old U.S. Information Agency (USIA), served innumerable residencies including six years as ensemble-in-residence at the Smithsonian, and released 24 CDs. But soundtracks? Is Hesperus serious?

“The thing is, it’s a brilliant idea. It’s a novel idea. But because it’s so well constructed and researched and performed, it’s not a novelty,” says Nell Snaidas (soprano, Renaissance guitar, co-curator GEMAS: Early Music of the Americas, among others).

In fact, those hundred-year-old movies turn out to be terrific at presenting 500-year-old music to 21st-century audiences.

‘Holy smokes, the soldiers are getting L’homme armé’

Chancey was skeptical at first. When an a/v technician approached Chancey and Reiss after a recording session in 2002 and asked if they’d ever thought of doing silent movie soundtracks, Chancey replied, “No, not really. We’re pretty busy. And it sounds like it’s really pretty hard.” But he lent them some Betamax video cassettes (it was 2002, after all), including Robin Hood. Chancey couldn’t resist.

As she watched, ideas sparked. “I thought, boy, it would be interesting to set some music to this,” she recalls. “And I have the kind of mind that makes leaps, you know. So I was watching, and a piece of music came to mind and I thought, well, OK. I kept watching, and different pieces of music came to mind for different scenes. And I thought, well, this wouldn’t be so hard.”

Chancey knows a lot of tunes. Ask how many and she’ll deflect by telling you how Mike Seeger, the folk music legend, would answer: “20, I learn 20 and then it pushes the old 20 out.” She knew Seeger. He played on Hesperus’ first album, Crossing Over, in 1988. Chancey, already a veteran early bowed strings specialist, had been performing Medieval and Renaissance music since the ’70s as well as American folk, Celtic, Sephardic, Balkan, and old-timey tunes—among many others. The material from which she can draw is nearly endless.

From it, she’s set each movie project to music appropriate to the era suggested by the story. The Hunchback of Notre Dame, for instance, gets 16th-century French and Burgundian music (with some 14th-century as well, to use Machaut and Dufay). Häxan, a 1922 pseudo-documentary on witchcraft, gets the 13th-century Cantigas de Santa Maria and 15th-century Oswald von Wolkenstein.

These scores are played with movies, of course, but they function just as well in concert, so they get two for one. In fact, playing this kind of early music as soundtracks addresses a need that is often expressed by musicians programming it. Medieval and Renaissance repertoire is made up of pieces that are often only two or three minutes long; stringing 30 of them together into an absorbing concert experience can be challenging. But a full-length movie’s narrative structure—its plot, scenes, editing, characters—turns out to be a wonderful device for organizing all those little parts into an effective whole.

Pairing music and visuals like that is something Chancey is made for. In Robin Hood, for instance, she assigns a jaunty Renaissance number like “Pastime with Good Companie” to the Merry Men of Sherwood Forest and sinister-sounding medieval French tunes to their enemies.

“They’re musical identifiers that go back and forth with the characters,” says soprano Snaidas. “If you don’t know anything about early music, it still works really well. But if you do know, you’re thinking ‘Holy smokes, the soldiers are getting L’homme armé—that’s perfect!’”

‘It’s wonderful when you can play early music in some sort of original context—when you get to play a dance for dancers and learn things about the music that you can’t learn any other way.’

As much as the tunes add to the movies, however, the movies add to the tunes, too. Players find the experience of playing to them revelatory. Grant Herreid (plucked strings, winds, voice, Piffaro, Ex Umbris, Ensemble Viscera) says:

“It’s wonderful when you can play early music in some sort of original context—when you get to play a dance for dancers, for instance, and learn things about the music that you can’t learn any other way. For me, one of the biggest draws of the soundtracks is that we get to play music in context. When you get to do a whole story, doing a battle piece or when they’re sword fighting, accompanying a love scene on the screen, it gives context. Lots of things fall into place.”

‘A perfect seven-layer cake’

What’s noteworthy, maybe, isn’t that Hesperus is doing silent-film scores but that it took them so long to start. Improvisation is something that lies at the core of what Hesperus does. It figures on all their albums from the very first, Crossing Over; Chancey and Reiss taught improvisation workshops for years. It’s still Chancey’s passion.

And improvisation provides a real link to the way silent-movie music was played back in the day. Accompanying the silents was largely an improvised art. The studios might have provided composed soundtracks and orchestras for movie premieres, but once the movies went out to local theaters, accompanists were more or less on their own. They could buy commercial music marketed to silent film players if they wanted. Chancey ran across one of these collections in Cleveland when she was 12. “It was great,” she says. “It had a piece that said, ‘love song’ and one that said, ‘fight music.’” But day to day, according to historians, accompanists were likely just to noodle things they liked to play.

Hesperus channels these forbears. Chancey is playing music that she loves, and she’s shaping the pieces into soundtracks through improvisation.

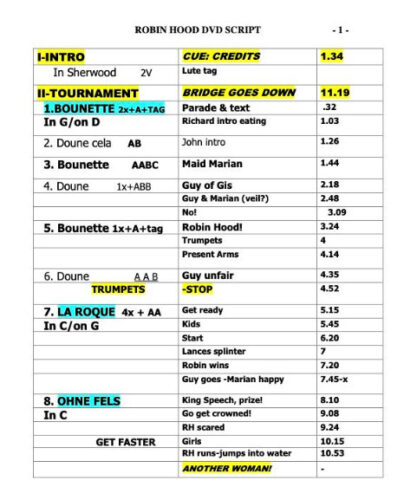

To start a project, first Chancey watches the film and, basically, noodles, finding tunes that work with what she’s seeing on the screen. Then she brings in her players. “And we tighten it up—sculpt the music to the action, tweak it, add transitions, find the rhythm of the scene, reinforce the strong visual gestures,” she says. “We’re not just playing music while the actors act, we’re supporting the action with rhythm and melody.”

The degree of improvisation that remains in the final project varies from movie to movie. The Three Musketeers probably has the least, as it includes episodes of highly composed Renaissance polyphony. The Mark of Zorro has the most—for that one, Chancey upped the ante by insisting her players improvise in the manner of Ortiz and his 16th-century colleagues.

Her players have a lot to do in any event. “It’s not for the faint of heart,” Chancey admits. Consider that all the movies are at least an hour-and-a-half long and that the music never stops. And that, in concert, players have keep to one eye on the sheet music (for cues, even if they’ve memorized it), one on the road map with tunes and times that Chancey provides, one on the movie, one on the other musicians—that’s already four eyes—all the while preparing to go off-book into improvisation as well as to pick up and put down instruments (hoping they’re still in tune).

But she has stout-hearted collaborators. Many she’s known and played with for decades, ever since they were coming up together in ’80s New York (Grant Herreid, Snaidas, the late Tom Zajac, among others). When Reiss, then of the Folger Consort, which he’d co-founded, lured Chancey to Washington, D.C., it was into another blossoming early-music and folk scene. It appears to have been a magical time when players, in effect, were learning a new language together.

“There were just so many more gigs and low-key opportunities to play lots of rep for a long time that just doesn’t exist nearly as much now—so many dance jobs and Ren Faires and tours, even just more concerts in general,” says Priscilla Herreid (recorders and reeds, voice, Piffaro artistic director). Herreid is regretful, perhaps, that she came up too late to catch it herself. Back then people memorized the first volume of “HAM,” a.k.a. Willi Apel’s Historical Anthology of Music Volume I: Oriental, Medieval and Renaissance Music, as well as, yes, the Ortiz Trattado de Glosas and other treatises.

The new soundtrack collaborators, including Priscilla Herreid herself, had to take different routes to get the same familiarity, but they got there. Herreid found her way in Piffaro and at Juilliard. Brian Kay (plucked strings, percussion, voice, Apollo’s Fire, Twa Corbies, Trio Sefardi, Divisio) describes spending untold hours at Peabody Conservatory (where former Hesperus member Mark Cudek is professor in Historical Performance) improvising on ground basses, chord patterns and songs, and going deeper into French estampies, Italian stampitas, the Cantigas de Santa Maria.

Niccolo Seligmann (bowed strings, Alkemie, The Broken Consort, Wherligig) credits the viol circle around John Moran in Virginia and the Viola da Gamba Society of America’s Washington/Baltimore chapter—where Seligmann got to know Chancey—as a nurturing force for like-minded musicians. And the Peabody scene gets credit, too, including a weekly gig where Brian Kay and Seligmann would improvise for hours at a Persian restaurant in Baltimore.

A soundtrack only comes together in the execution. “It can be a really intense experience” says Kay. “The rehearsals seem long because we’re sitting and watching these silent films over and over again. But then when we do the concert and it just goes by like that because it’s just so invigorating.”

“These movies are sort of a perfect seven-layer cake,” says Priscilla Herreid, “to show off what musicians can do.”

The performers who play on Hesperus’ soundtracks are otherwise busy, mid-career, in-demand players. But they drop what they’re doing for the soundtracks, even with the amount of preparation they require.

Chancey is to a large extent the reason why. It’s not just her skill at what she does, although that’s part of it: “She’s remarkable, the most beautiful gamba player—she can play a drone for five minutes and make it sound really interesting and cool, and she can play a melody like nobody,” says Grant Herreid.

Or her musicianship: “Her performers are always either great improvisers or she forces them to improvise, and they become more and more spontaneous. I became a much better musician after I played with Scott and Tina for several seasons. You just have to get better to play with her,” says Mark Cudek.

Or her long experience: “She’s kind of a storyteller, too, and when she talks about her days with groups and the history and people who were involved, I get this sense of this modern history of early music through her stories. It puts me in it—in my own place—where I am within that entire movement,” says Kay.

It is all of these, of course. “I feel like we’re in a Marvel movie,” says Snaidas. “And the more I perform with her, the more I amass all these moments of Tina being a superhero.”

But with five decades of performing and two of creating soundtracks behind her, Chancey’s not resting on any laurels. The soundtracks themselves are slowly morphing. Over the past decade of producing the soundtrack DVDs, Chancey has become absorbed by the technical and creative aspects of filmmaking, including a brief apprenticeship with composer and documentary soundtrack producer Brian Keane.

The recordings reflect her new abilities in creating soundscapes through layering, adding, and editing. She’s trying out new sounds, inviting Rex Benincasa into the group for what Chancey calls a “plethora of percussion” and Spiff Wiegand for a plethora of everything else including banjo, accordion, hurdy gurdy, didgeridoo.

The new soundtracks involve a lot of tape. Half the music for the Häxan soundtrack in 2021, for instance, was group improvised and half overdubbed. Nosferatu, also in 2021, was the first of her soundtracks to depart from early music, conjuring vampiric Transylvania through electronic sounds and dubbed Balkan instrumentalists. In summer 2022, she began recording tracks for the next project, the 1920 expressionist masterpiece, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

Musicians who have joined Chancey more recently have considerable experience with the assembly-line process of commercial soundtracks: among other projects, Kay and Seligmann both contribute to Netflix’s The Witcher and Seligmann to the Civilization VI video game.

But when they play with Chancey, they play by Chancey’s rules. Chancey and Kay developed Häxan’s basic footprint while sitting in recording booths watching the film and throwing medieval tunes back and forth to each other.

Seligmann describes an email they received with suggestions to prepare for their improvisations on Häxan. Over the passamezzo antico repeating bassline, Chancey wrote, Seligmann should “have a conversation with someone who wants to buy you a drink but you think he’s slimy and he won’t take no for an answer, so it escalates” or “meditate quietly over all the ways you love your partner.”

Asked who’s going to run Hesperus when she retires, Chancey, now 73, answers: “You know, some groups grow and thrive after their founders leave. They become established, and that’s wonderful. But Hesperus grew out of the other side of early music—two curious people following their own personal takes. Scott and I were into spontaneity and improvisation to bring the past alive. We just hoped it would resonate with people.”

It has. “Tina sets an example I try to follow, especially as a medieval-music performer, but just throughout all of my playing,” says Seligmann. “I think of being in her pedagogical lineage. Many of the skills I pass down to my students, I learned from her.”

“She’s a trailblazer,” Seligmann adds. “We are her biggest fans.”

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer and art historian living in Philadelphia. anneschusterhunter.com