Making Music in Early America exhibit depicts Virginians and their instruments

“In Williamsburg… I hear from every house a constant tuting may be listnd to upon one instrument or another” – Landon Carter, Virginia Planter, 1771

Who played music in colonial Virginia?

Someone might answer “Thomas Jefferson!” or “Didn’t Patrick Henry play the fiddle?”

True and true, but 18th-century Virginia was a big place, and one of Colonial Williamsburg’s newest exhibits, Making Music in Early America, demonstrates just how much music could be heard from some of the people who populated it.

Peter Pope was probably born in Virginia around 1762. We don’t know much about him. We know he was born into slavery, and that in October of 1779 he emancipated himself and enlisted into the ranks of the Hessian infantry as a drummer. For Peter, making music meant freedom.

Peter, the first character we meet in Making Music in Early America, is represented by a life-sized print of an African-American drummer (by artist Don Troiani). Clothed in the military uniform of Hesse-Hanau, the stoic musician-soldier stands beside a rare brass side drum, built between 1775 and 1788. Manufactured in Germany’s Waldeck region, this drum is the type of instrument Peter would have used during his time in the Hessian service.

‘Nearly every artifact on display is accompanied by a portrait or print of a historical figure associated with similar instruments’

This connection between imagery, artifact, and story is a theme that permeates the gallery. “It’s about people, it’s about accessibility,” says Amanda Keller, Colonial Williamsburg’s Manager of Historic Interiors and the new exhibit’s curator. “The instruments become even more fascinating when you discover who played them and what role music played in society.”

For the last 96 years, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation—an enclosed museum-town, called CW by the locals—has championed the preservation of Virginia’s bygone capital. The museum encompasses a 301-acre Historic Area with 88 original 18th-century structures and hundreds of reconstructed buildings. Historically informed sounds—from carpenters, wheelwrights, blacksmiths, and more—emanate from the windows of trade shops as costumed interpreters revive and preserve the industrial culture of 18th-century Tidewater Virginia. Careful listeners may even hear a tune by Corelli or Schwindl being rehearsed by the in-house, period-instrument ensemble, the Governor’s Musick.

Just outside the Historic Area is one of CW’s best-kept secrets: The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, and its Mark M. and Rosemary W. Leckie Gallery, which opened in August 2022.

Making Music in Early America is the inaugural exhibit for this new permanent space for music exhibitions. As the gallery’s chief steward, Keller recognizes music’s natural connection to the lives of Virginia’s 18th-century residents. Her perspective on these connections has largely been shaped by her work researching, designing, and implementing furnishing scenarios for the Historic Area’s exhibition buildings.

“I read primary sources like probate inventories, diaries, and letters and often encounter references to musical instruments, performances, and even receipts for music lessons or visits from dancing masters,” Keller says. “It made me look at objects like a hunting horn and see the possibilities of being able to tell a really diverse story of early American life.”

As CW’s largest and most varied music exhibit, the gallery features some 60 original instruments from the 17th through 19th centuries. Through these instruments, the exhibit introduces and explores a variety of cultural narratives related to 18th-century Virginia. Amy Miller, a CW music supervisor and flutist with the Governor’s Musick, puts it succinctly: “Every instrument in the exhibit tells a story.”

Making music at home

Inside the plantation houses and townhomes of British America, women of means were at the center of domestic music making. As the capital of Virginia from 1699 to 1780, Williamsburg was home to a significant concentration of affluent families eager to replicate cultural trends coming from London—accomplished, in part, through the musical education of wives and daughters.

Thus, Making Music in Early America includes an impressive display of portraiture featuring women amateurs with connections to the area. Ann Taylor Roberts sits with a harp built by George Froschle (London) in 1793. Caroleana Carter holds a guitar by James N. Preston (London), built between 1765 and 1775.

Ann Blaws Hansford Barraud’s portrait doesn’t include a keyboard, but she’s displayed next to an instrument whose design she would have known, an 1831 square piano, built in Baltimore by Joseph Newman. Barraud was esteemed locally for her skills as a pianist, and three bound volumes from her music collection are preserved at the College of William & Mary’s Swem Library. Notable in her collection are works by Haydn, Handel, and William Shield.

Kyle Collins, a historical keyboardist and the newest member of the Governor’s Musick, has taken inspiration from Barraud’s story. Throughout the autumn of 2022, Collins presented works from her collection in the Leckie Gallery on an instrument that Barraud practiced on: the museum’s rare 1799 Longman, Clementi & Co. Organized Piano (London).

This unusual instrument was delivered to St. George Tucker of Williamsburg in 1799, and surviving letters indicate Barraud was playing this piano that same year. It is the only extant upright grand piano of its type and, as a playable instrument, is a remarkable connection to domestic music making in Williamsburg.

Barraud’s “musical collection indicates a skilled artist with her finger on the pulse of the latest musical trends,” says Collins. His program in the exhibition was intended to give audiences “a succinct glimpse into the musical world of Williamsburg after the Revolutionary War.”

Collins plans on continuing his presentations in the Leckie Gallery into the summer of 2023, in a program called “Domestic Diversions” which, like his program on Barraud, uses surviving score collections to introduce visitors to 18th-century Williamsburg’s musical residents.

Musician, clerk, jailer

The women featured in Making Music in Early America typically studied with itinerant teachers and music masters who found themselves in the Williamsburg vicinity. Before the Revolution, the Virginia Gazette carried advertisements for lessons on French horn, oboe, flute, recorder, violin, harpsichord, and piano. The most famous music teacher in 18th-century Williamsburg was Peter Pelham, who looms large throughout the exhibit.

Born in London in 1721, Pelham’s family moved across the Atlantic to Boston, around 1730. The lad studied organ and harpsichord with Charles Theodore Pachelbel, the eldest son of Johann Pachelbel (of “Canon in D” fame). By 1744, Pelham was teaching students of his own and working as the organist of Trinity Church, Boston. Pelham’s only surviving music comes from a manuscript copybook of this period.

The 1744 manuscript was written as a keyboard tutor for one of Pelham’s students in Massachusetts and is part of the CW collection. While the original copybook is too fragile for display, Making Music in Early America features high-quality digital scans that visitors can access by a touch screen. In addition to original compositions by Pelham and C.T. Pachelbel, the manuscript contains works by Lully, Handel, and Arne, offering a glimpse into Pelham’s tastes.

In the early 1750s, Pelham moved to Virginia. His appointment as organist to Williamsburg’s still-active Bruton Parish Church in 1755 was a musical win for the small city. Despite the fact that Williamsburg was home to British America’s first theater, built in 1718, Pelham is the only professional musician who resided there for any meaningful period of time during the 18th century. There was, of course, a reason for this.

By 1775, the slave trade and tobacco production made Virginia the wealthiest of Britain’s North American colonies. Despite this affluence, as Making Music in Early America notes, “Neither Williamsburg nor any other Virginia city had a population sufficient to support a full-time professional musician.” Consequently, Pelham was forced to cobble together a living with additional jobs—then as now a gig economy—such as government clerk and jailer.

Still, he found time to pursue creative ventures. In 1768, Pelham led a Williamsburg performance of Johann Christoph Pepusch’s wildly popular 1728 stage piece, The Beggar’s Opera. Pelham would remain an important musical figure in the area until his death, just after the turn of the century.

Virginia’s Black community

The story of Peter Pope, the once-enslaved drummer introduced earlier, is not unique. Peter was one of an estimated 210,000 enslaved people—about 40 percent of the total population—living in Virginia in 1775. The instability caused by the War of Independence, paired with policies of emancipation being practiced by British and Hessian forces, allowed Peter and others in his situation to find freedom through military service. We don’t know what happened to Peter after he enlisted in 1779, but we know that at least 31 Black musicians moved to Germany with their units following the war’s conclusion.

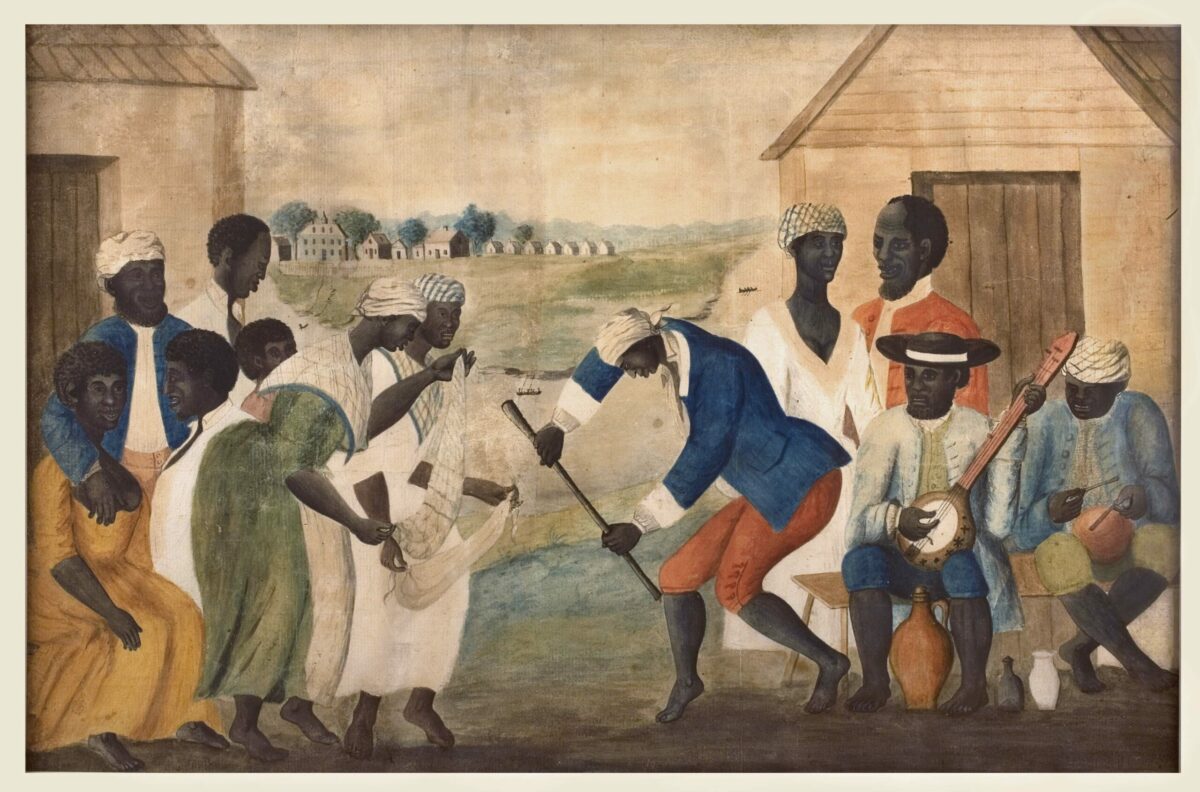

Making Music in Early America also provides context for music making in Black communities when the new nation wasn’t at war. In the face of tremendous brutality, enslaved people in 18th-century America cultivated musical lives that blended traditions from West Africa with those of their enslavers. Anyone who has spent time with this subject is likely familiar with the c. 1785 painting Music and Dance in Beaufort County (The Old Plantation), attributed to John Rose (c. 1752–1820) and held in CW’s collections.

A print of this work in the exhibit is paired with a reproduction gourd banjo (built in 2005 by Baltimore instrument maker Peter Ross). Visitors are introduced to music making on the plantations of the American South through the display’s focus on individual figures from John Rose’s painting. By isolating the musicians and their instruments, notably a drum, gourd banjo, and shekeres, the viewer has an opportunity to become more intimately acquainted with the details of the scene, and how elements of West African culture were preserved in America.

Though an uncomfortable source, newspaper ads trying to track down runaways provide detailed descriptions not only of what self-emancipated people looked like and wore, but also of skills they had. Making Music in Early America displays several ads from the Virginia Gazette that feature talented singers, violinists, and multi-instrumentalists. In this section of the gallery, the exhibit also features the most famous Afro-Virginia fiddler of the 18th-century, Simeon—also known as Sy—Gilliat.

Sy Gilliat is a legendary figure. If not for a few key pieces of evidence, such as a printed death notice from October 1820, it would be difficult to argue he was a real person. We know that Gilliat died on October 15, 1820, in Richmond, but we don’t know, however, the circumstances of his birth or have a clear picture of his status as a free or enslaved person. Allegedly, he was at least a servant to Virginia’s royal governor Lord Botetourt between 1768 and 1770, where he provided music for the social events at the Governor’s Palace. More definitively, Gilliat became a leading fiddler in Richmond during the early decades of the 19th century, where he performed in duo with clarinetist and flutist Landon Briggs.

While Making Music in Early America is split into distinctive sections, the exhibit ultimately demonstrates how the lines that divided different musical spheres were often blurred. Theater orchestras were staffed by amateurs, music teachers, church musicians, and touring artists. Military music was made by those who grew up in the ranks and those who fled to them for freedom. The wealthiest of Virginia’s gentry were entertained by both enslaved and free Afro-Virginian fiddlers and horn players.

So who played music in 18th-century Virginia? Just about everyone.

Noticeably, Making Music in Early America does not include original instruments and narratives related to Virginia’s American Indian population. This was an intentional decision.

As an introductory panel reads, “Music and dance were integral parts of American Indian life in the 18th century, as they are today. Out of respect for the Virginia Indian community, this exhibition does not display musical instruments from their cultures. Their…instruments are considered sacred and are actively used in ceremonies. Many have been passed from generation to generation and may not be performed before outsiders.”

Curator Keller’s future plans for Making Music in Early America include expanding the exhibit’s narratives by periodically refreshing the space with new and different instruments. This year, the gallery will welcome at least one new addition: an anonymous Bohemian bass viol, built c. 1750, from the Caldwell Collection of Viols.

The steward of the Caldwell Collection, renowned viola da gambist and pedagogue Catharina Meints Caldwell, has strong links to music in this historic city. Two of her former students, Wayne Moss and Jane Leggiero, served as gambists with the Governor’s Musick. As an active member in the national viol community, the ensemble’s current gambist, Brady Lanier, played a key role in bringing the 1750 viol from Caldwell’s collection to CW. It is planned that this instrument will go on display as a part of Making Music in Early America where it will serve not only as an addition to the exhibit but also as an homage to Caldwell’s musical legacy at CW.

Other immediate plans for Making Music in Early America include participating in CW’s annual antiques forum. The four-day conference will be celebrating its 75th anniversary this year—February 24-28, 2023—and will be themed Past, Present, and Future! Visitors can expect to see and hear instruments from CW’s collection as the Governor’s Musick and the Leckie Gallery share Williamsburg’s rich musical past.

Dominic Giardino is the Executive Director of Arizona Early Music, a board member of Early Music America, a freelance historical clarinetist, and an independent researcher of military music in the early Atlantic World.

Dominic Giardino is the Executive Director of Arizona Early Music, a board member of Early Music America, a freelance historical clarinetist, and an independent researcher of military music in the early Atlantic World.