by Mark Kroll

Published July 18, 2022

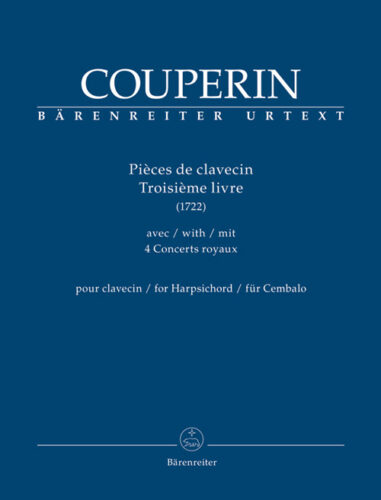

François Couperin, Pièces de clavecin, Troisième livre (1722) with 4 Concerts royaux. Bärenreiter, BA 10846 (2021). 142 pages. Denis Herlin, editor.

Good news for anyone who loves the music of François Couperin, the French Baroque, or early music in general. The third installment (Book III) of Denis Herlin’s edition of the complete Pièces de clavecin for Bärenreiter has recently been published, and I am pleased to report that it is as excellent as those for Books I and II, and perhaps even better.

EMA readers might remember how enthusiastic I was about Herlin’s edition of Book II in my 2018 review of that publication, and that I considered it superior to all earlier editions. Herlin’s Book III doesn’t disappoint and maintains the high level of the series. It follows the general formats of volumes I and II, beginning with a lengthy preface (in both French and English) that, like its predecessors, is so full of interesting and useful information that it could serve by itself as a scholarly article on the subject.

In the opening section on Couperin’s life and world during the period between the publications of Books II and III (1717-1722) we learn where he lived—“the rue de Poitou, in the district of the Marais du Temple”—and that Couperin was suffering from some health problems at this time. Herlin cites a letter from Antoine I of Monaco to Couperin that implies this, warning him to “Take care of yourself, Monsieur, and do not take on too much work, because your health will only suffer.”

(This is not the first time we hear of Couperin’s health problems, and unfortunately not the last. He writes in his own preface to Book IV of the Pièces de clavecin, published in 1730, that his “health declines daily [and] my friends have counseled me to stop working.” Nevertheless, he was able to complete that last book of harpsichord pieces.)

Book III, however, as Herlin correctly observes, “marked a turning point in the publication of the works of François Couperin,” because, in addition to the expected ordres (or suites) for solo harpsichord (here ordres 13-19), this volume also features four Concerts royaux, which Couperin tells us in his preface “are suitable not only for the harpsichord, but also for the violin, flute, the oboe, the viol, and the bassoon.” Couperin further explains not only why he composed them and when he played them—“for the small chamber concerts for which Louis XIV had me play almost every Sunday of the year”—but also gives us the names of his fellow performers: François Duval (violin), Anne Danican Philidor (oboe and bassoon), Hilaire Verloge Alarius (viola da gamba) and Pierre Dubois (oboe and bassoon).

Herlin adds that Book III “was the most substantial volume that Couperin ever published” because of the inclusion of these “royal concerts.” It was well worth the extra paper and printing, then and now.

The Concerts royaux had not appeared in any modern 19th- and 20th-century editions, but with this publication we now have a chance to compare Couperin the keyboard composer with Couperin the chamber musician in a single volume, “which was Couperin’s preference and intention.”

Herlin’s preface also reveals some interesting personal insights into Couperin as a husband and father, such as his request in 1718 that his pension of 800 livres be divided equally between his wife and his eldest daughter Marie-Madeleine (1690-1742), which was granted. Marie-Madeleine, who eventually entered the nunnery, appropriately chose Saint Cecilia as her protector, and became the organist of Royal Abbey of Maubuisson. Couperin’s other daughter, Marguerite-Antoinette (1705 – ca. 1778), was also a musician, a professional one. She became a celebrated harpsichordist who succeeded her father in various court appointments and served as harpsichord teacher to the daughters of Louis XV.

The Couperin family dynasty, moreover, seems to have been as large and close as that of Bach. For example, Herlin describes how “the composer’s cousin, Nicolas Couperin (1680-1748), who had taken over the position of organist at Saint-Gervais in December 1723, continued to oversee the sale of the works of François Couperin, probably in agreement with the composer’s widow, until his own death in 1748.”

The Preface contains many other valuable and necessary pieces of information, such as the highly positive reception of Book III, new interpretations about the meaning of some titles of the pieces in it, performance practice guidelines about tempo markings and ornaments, and even a suggestion about the type of harpsichord (i.e., a Blanchet?) on which Couperin might have performed during the composition of the book. The absence of a dedicatory page indicates that Couperin was quite comfortable financially at this point in his life. He did not need any help from patronage.

The critical commentary, including all the sources of Book III that Herlin examined, is comprehensive, and the engraving of the music is of the high standards one expects from Bärenreiter. Notably, the current editor and publishing house once again managed to follow the efforts and careful planning of the composer and original engraver of Book III, Louis-Hector Hue (1699-1768), by avoiding as much as possible any page turns within each piece. All keyboard players will say merci for that.

Mark Kroll has recorded the complete Pièces de clavecin of François Couperin on both modern and 18th-century instruments, including those made by Taskin, Germain, Blanchet, Christian Kroll, and Zell. His book about the reception of the music of Bach, Handel, and Scarlatti in Britain from 1750-1850 will be published in the fall by Cambridge University Press, and the Slovakian translation of his biography of J. N. Hummel will also appear this year.

More Book Reviews:

No posts