by Carol Lieberman

Published September 9, 2019

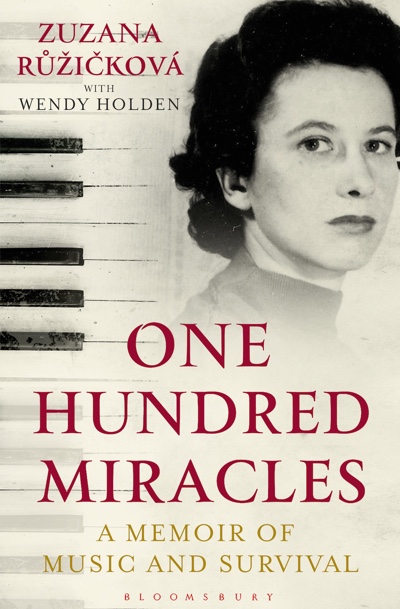

One Hundred Miracles: A Memoir of Music and Survival. Zuzana Růžičková, with Wendy Holden. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019. 344 pages.

Zuzana Růžičková (1927-2017) led a remarkable, in fact miraculous life as a celebrated harpsichordist who overcame starvation, disease, and slave labor in three Nazi concentration camps — Terezin, Auschwitz II-Birkenau, and Bergen-Belsen —and one labor camp, Hamburg. Despite these horrors, she managed to create an international concert career, record more than a hundred albums, become harpsichord professor at the Prague Academy, and have a happy marriage with the noted Czech composer Viktor Kalabis for 50 years. I had the great privilege to know Zuzana and Viktor as a friend and colleague for 25 years until her death at the age of 90.

One Hundred Miracles: A Memoir of Music and Survival is told in Zuzana’s own words, with the assistance of journalist Wendy Holden, who interviewed Zuzana just before her death. The book also includes interviews with Zuzana’s friends, fellow performers, and husband Viktor, plus information taken from the 2017 documentary, Zuzana: Music Is Life, directed by Harriet Gordon Getzels and Peter Getzels.

One Hundred Miracles: A Memoir of Music and Survival is told in Zuzana’s own words, with the assistance of journalist Wendy Holden, who interviewed Zuzana just before her death. The book also includes interviews with Zuzana’s friends, fellow performers, and husband Viktor, plus information taken from the 2017 documentary, Zuzana: Music Is Life, directed by Harriet Gordon Getzels and Peter Getzels.

Zuzana grew up in a middle-class Jewish family in Plzeň, Czechoslovakia, the only child of adoring parents, Leopoldina (“Mummy”) and Jaroslav (“Tata”). Zuzana tells us: “All of my childhood memories are happy ones. I think if you have a sweet childhood like I did then you can survive almost anything in later life. Nothing can really spoil it for you.” She had German and English governesses, became fluent in both languages, and was indulged by her grandmother Paula, who took her to the theater, concerts, and the opera. Therefore, when her mother told her she could have anything she wanted if she would only get well from a serious bout of tuberculosis and pneumonia at the age of 6, Zuzana immediately cried out, “Piano lessons!” Thus began her life in music.

And when her first teacher, Madame Maria Provazníková-Šašková, introduced the music of Johann Sebastian Bach to her, Zuzana described her reaction at the age of 8: “…it was almost as if I didn’t need the score — I was transported to a place I’d never been to before.” In fact, Madame’s first Christmas gift to her gifted student was Bach’s 48 Preludes and Fugues, telling her: “One day soon, Zuzanka, you will play these.” Madame, moreover, was convinced that Zuzana should take up music as a profession, but her parents were not so sanguine, arguing that “…Zuzana will never earn anything.” Nevertheless, her father finally asked, “What would you like to do, Zuzka?” She replied, “I dearly wish to study music, Tata.”

One Hundred Miracles also outlines in horrifying detail Zuzana’s unbelievable survival in the Nazi camps. The book’s title is, in fact, taken from Zuzana’s own words: “I am not a person of extraordinary strength. I survived all the camps and the terrible experiences not because of myself, it had nothing to do with me. It was one hundred miracles.”

One was the fact that Zuzana managed to stay with her mother in all the camps, something that saved both their lives. So did music. Zuzana carried with her part of a Bach sarabande she had jotted down on a slip of paper. It was the last piece she had played with Madame. As Zuzana remembers: “In the music of Bach there is the utmost joy of life, and also the most desperate sadness. One always feels the deep sense of being human.”

Zuzana shares some details of her horrendous experiences in the camps. In Hamburg, for example, she was forced to load bricks, a task that ruined her hands and nearly cost her a career in music. Bergen-Belsen, however, was the worst, Zuzana telling us that the only expectation was for the prisoners to die. Dead bodies were piled everywhere, there was nothing to eat and no work to be done. Zuzana volunteered to carry the dead to the pyres in exchange for some soup. Finally, she was liberated by the British on April 15, 1944, taken to a hospital, treated for typhus, and also found her mother, almost dead. One day, they heard a radio broadcast from Madame, who was looking for Zuzana from Pilsen. Yet another miracle.

Zuzana first played the harpsichord in 1949 while studying piano at the Prague Academy. With the help of Madame, she hoped to study harpsichord in France with Wanda Landowska, but this was not to be: Czechoslovakia was now a communist country, and Zuzana was not allowed to travel to “capitalist” America.

Zuzana married Viktor in 1952. It was a difficult decision, since he was not Jewish and there was rising anti-Semitism, with hundreds of show trials condemning Jews to death. Anyone who was allied with a Jew was known as a “White Jew,” affecting their lives as long as the communists were in power. Viktor was always under suspicion both for his music and his political views, and he was only allowed to teach unqualified students how to conduct. Finally, he was permitted to conduct a children’s chorus. Zuzana and Viktor thus had to lead double lives “in a permanent climate of secrecy and fear.” I once asked Zuzana and Viktor what was worse: the concentration camps or 40 years of communism? They replied without hesitation: “Communism!”

In 1955, Zuzana was encouraged by friends to apply for the ARD International Music Competition in Munich, Germany, which had a category for harpsichord. Agonizing as to whether she should even go to Germany, Viktor persuaded her: “…it is really your duty to go there — as a Jewess and as a former prisoner. You will be showing them that someone who is not German and is not an Aryan can play Bach. You will be proving to them that Hitler was not the last word.”

Although no winner was declared, Zuzana was given a development grant meant for the contestant the jury felt was most worthy, writing that they would very much welcome her to continue her studies in France or Germany. As she describes: “I was twenty-nine years old, I had been honoured in a most prestigious competition for playing the harpsichord, the instrument I decided …would be the one I would dedicate my life to. I was so in love with Viktor, and finally able to feel the kind of joy again that I had known as a child.” Her performance in Munich sparked the beginning of her solo career.

It is impossible here to provide all the details about the miraculous life of Zuzana found in this book — it is must reading for anyone interested in the history of the harpsichord and early music in the 20th century, and as a model of courage, resilience, and dedication. Holden has not only shaped a memoir of Zuzana Růžičková and her life as a great performer. She has also chronicled one of the darkest times in European history and demonstrated one person’s ability to overcome them through her dedication to life and music.

Carol Lieberman recently returned from London, where she gave a lecture-demonstration on the subject “What We Can and Cannot Learn About Performance Practices from Early Recordings.” Centaur Records has just released a two-CD set of her recordings on baroque and modern violin made over the past 50 years: The Art of Carol Lieberman (CRC 3701 and 3702).