by Christa Pehl Evans

Published April 12, 2021

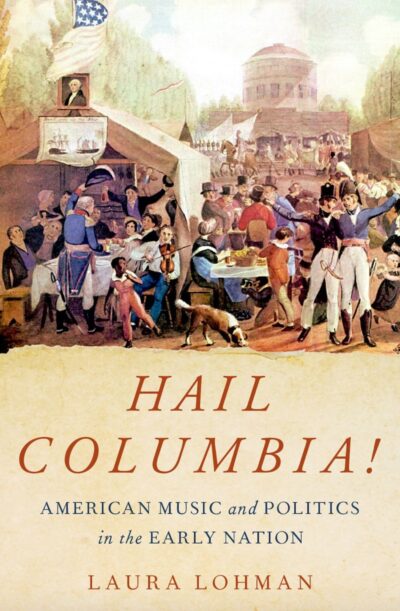

Hail Columbia! American Music and Politics in the Early Nation. Laura Lohman. Oxford University Press, 2020. xiii + 326 pages.

Anyone befuddled and amused by American politics and the media today will find historical solace in this timely read. In a much-needed interdisciplinary book, Laura Lohman examines the use of music as partisan propaganda on the American political scene. Beyond just an analysis of text, she expertly weaves together the connotations of the tunes themselves with the historical context in the political moment. A significant contribution to the field of American history as well as musicology, Hail Columbia! provides a detailed analysis of popular American songs on the political scene in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

The book is structured chronologically, with each chapter centered on a historical event. Lohman begins big by considering how music was used to create the legend that surrounds the drafting and ratification of the Constitution. Protests were suppressed, and importance of unification were told and retold in print and in song, making a stronger federal government seem necessary rather than imposing.

The book is structured chronologically, with each chapter centered on a historical event. Lohman begins big by considering how music was used to create the legend that surrounds the drafting and ratification of the Constitution. Protests were suppressed, and importance of unification were told and retold in print and in song, making a stronger federal government seem necessary rather than imposing.

Lohman explores how music was both propaganda and protest further in the second chapter, which focuses on Washington’s second term. Both Federalists and Republicans used music to express their oppositional political views. Framing their debate in the language of “natural rights” à la Thomas Paine, Americans disseminated what was essentially propaganda, praising popular cosmopolitanism and rejecting British influence.

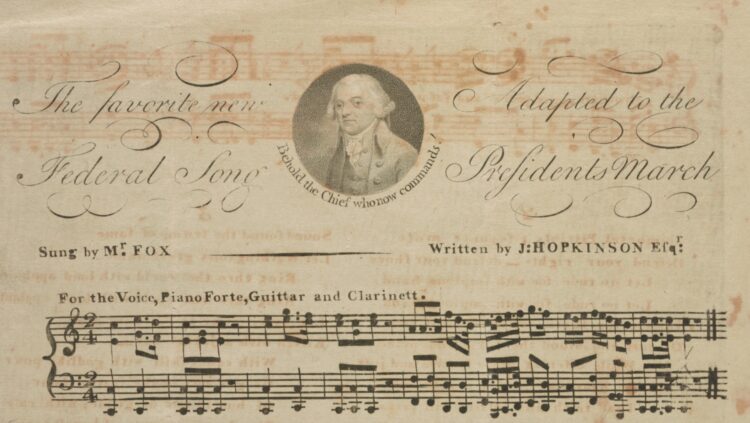

Chapter Three discusses the role of music during John Adams’s contentious presidency. Lohman dissects how both Federalists and Republicans used the same tunes to carry texts that villainized the opposing political party. Particularly amusing is Lohman’s analysis of “Hail Columbia,” for which Joseph Hopkinson set lyrics to Philip Phile’s “The President’s March,” originally composed in 1789 for George Washington’s first inauguration. The song had its premiere at Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street Theatre in April 1798 after the orchestra was “driven off” by the audience in a controversy over whether to play “Yankee Doodle” or “Ça Ira.” Tensions due to the XYZ affair were high, and song again proved played a pivotal role in both unifying and dividing.

Detailing further how music was used to craft myths of political dominance, the fourth chapter moves the reader into the era of Thomas Jefferson’s presidency, beginning with his contentious election. Lohman captures how Federalists and Republicans sparred in song. Through music and other propaganda, Jefferson was portrayed as Washington’s Messiah, erasing Adams’s contentious presidency in popular view. Ultimately, song helped to deflate the Federalist party.

In Chapter Five, Lohman examines a resurgence of partisan tensions in the period of 1806 to 1811 during the presidencies of Jefferson and Madison. Central to this chapter is music responding to the controversial embargo, restricting trade in response to the Napoleonic Wars. Essentially, the larger goals of the nation were debated through song, with questions about the navy, the economy, and American diplomacy set to popular tunes.

Not one to shy from big topics, Lohman addresses the War of 1812 in the final chapter, including an analysis of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Francis Scott Key’s avoidance of partisan language and regional differences in his hyperbolic lyrics made for a song that was the perfect vehicle to reunite a nation rattled by a controversial war. “Key could have offered an alternative but less comforting explanation of the battle,” Lohman notes. She also investigates some of the more cynical music written during these years.

My favorite part of this text was reading it with the accompanying website, which includes links to audio recordings, images, and additional texts. There is so much food for musicians to sing and perform the music Lohman has unearthed and contextualized. I hope they will use Lohman’s work as a launching point for performances and recordings.

An interesting and entertaining read, Hail Columbia! illustrates how political ideas were debated in song and how the myth of a unified America was crafted through music. Lohman’s study also serves as an example of how to harvest information from the large body of music that emerged from the tradition of balladry and broadsides in England, America, and beyond. Her recipe is this: dissect the layers of meanings held by the popular tunes that were vehicles to lyrics rewritten and rewritten across time, analyze the lyrics themselves, and move beyond words into the socio-historical context of the specific songs at hand.

Scholar and performer Christa Pehl Evans is an assistant professor of music at Fresno Pacific University. Her research explores musicians and their manuscripts in late 18th-century Pennsylvania and has recently been published in Current Musicology.