by Valerie Walden

Published October 7, 2019

Sir Henry Wood programmed and conducted concerts at the Proms in London from 1894-1944.

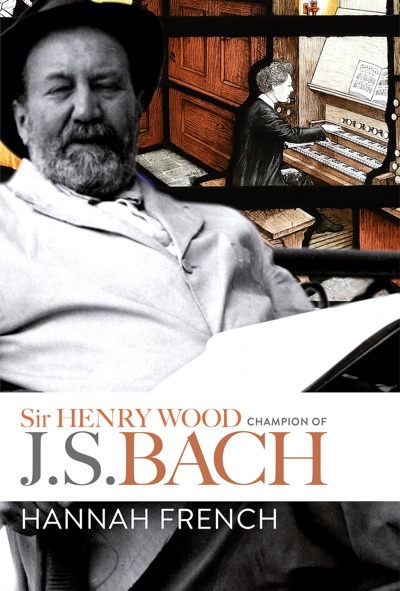

Sir Henry Wood: Champion of J.S. Bach. Hannah French. The Boydell Press, 2019. 327 pages.

Sir Henry Wood is not a name recognized by most American musicians. Co-founder and conductor of the London summer promenade concerts, now known as the Proms, from 1894-1944, Wood was an innovative programmer whose concerts frequently featured “new” music; he premiered 717 compositions by 357 contemporary composers, including Bartok, Hindemith, Prokofiev, and Stravinsky. He also loved the works of Johann Sebastian Bach and brought his music to thousands of listeners, introducing many of them to the composer for the first time.

Viewing Wood as an unappreciated figure in the “Bach revival” movement, Hannah French has industriously researched the scores and orchestral parts of the Bach works belonging to the conductor and used for his performances — heavily marked with performance notations. Donated by Wood to the Royal Academy of Music in 1938, they provide a detailed view of his approach to programming, interpretation, and musicianship, simultaneously documenting English orchestral performance practices of the era. French has organized her material into five sections, each richly illustrated with reproductions of the scores, orchestral organization lists, graphs, and tables showing orchestra details, metronome markings, structure and instrumentation of Bach’s orchestral works, as well as excerpts of Wood’s own transcriptions of this music.

Part 1 overviews the general musical environment and concert programming, as well as the audience reception to Bach’s music, that predates Wood’s career. Although the book does not provide a complete biography of the conductor, Part 2 details enough information to explain how Wood came to know Bach’s music and then follows Wood’s introduction and expansion of Bach programming through his tenure at the Proms. This section also interestingly documents and provides details about the musicians who performed this music.

Wood’s interpretation of both Bach’s orchestral and vocal music is the purview of Parts 3 and 4. His particular focus for orchestral performance were the Brandenburg concertos and the orchestral suites. One of the novel aspects of Wood’s work patterns was his goal to streamline rehearsals. He gave his players thoroughly marked parts with performance instructions and maintained stringent budget constraints, resulting in minimal rehearsal time. These parts provide a wealth of information for French to share with her readers. In Part 3, the author also examines Wood’s use of differing editions, details his few recordings, and compares his interpretations with the recordings of other noteworthy conductors. Also documented is Wood’s proposed edition of the Brandenburg concertos with Boosey & Hawkes.

In Part 4, French looks at the cantatas, with special attention to Wood’s orchestrations, and his numerous performances of the Passions and the Mass in B minor, although many of these performances were at locations other than the Proms. Part 5 analyzes Wood’s influence in popularizing Bach’s music as part of the London “Bach revival.” These chapters contain more information about how Wood’s audiences responded to his performances and the continuing legacy of his contributions. The book concludes with an epilogue and nine appendices that contain further details about Wood’s working life. Appendix B is of special note, as it is the syllabus and existing notes to a lecture that Wood gave on Bach’s life in 1901.

There is no question that French venerates her subject, and her careful presentation of Wood’s materials is well organized and informative, although more biographical information would offer deeper insights into understanding the conductor and his contributions. Where the book falls short is the context in which Wood’s achievements are placed. Wood did introduce the music of Bach to many who were unfamiliar with Baroque music, but so did many other performers and conductors of the era, and earlier. French’s assessment of 19th-century familiarity and appreciation for Bach’s music is therefore somewhat confusing and incompletely sourced. The author also relies primarily on the 1896 accounts of F. G. Edwards to paint the picture of Bach performances in the first half of that century, information that has been substantially updated by modern scholarship; for instance, both Mendelssohn and Ignaz Moscheles gave far more performances of Bach in London than are mentioned in Edwards’ articles or in this book.

The chapters of Parts 1 and 2 sometimes blur the issue of whether or not 19th- and early 20th-century audiences truly enjoyed Bach’s music or considered it dry and overly complex. In Chapter 1, for example, French cites Musical Times’ writer James W. Davison’s 1844 opinion that “Bach must be regarded rather as a curiosity than as a specimen of musical beauty,” but this viewpoint is contradicted without context in Chapter 2, when she writes that “Bach has been left too much to musicians and too little to the people.”

Another apparent contradiction is French’s inference that Wood’s study of Bach as a student was unusual, but then goes on to describe the number of musicians with whom he studied Bach, the organ teacher Henry Charles Tonking in particular, demonstrating that Bach’s music was well known to the generation of English performers who preceded Wood. We can consequently surmise from the documentation that then, as now, some listeners appreciated Bach’s music and others didn’t, but this is not the point that the author strives to make.

These criticisms aside, readers of this book will gain a deep appreciation for the ground-breaking achievements of Sir Henry Wood. With the rich detail of his performance methodology now documented and readily available, he can be remembered not only as a promoter of Bach, but also as a conductor who helped raise the musicianship of England’s orchestral performances to the high level enjoyed by 20th- and 21st-century audiences.

Valerie Walden is the author of One Hundred Years of Violoncello; A History of Technique and Performance Practice, 1740-1840; a chapter in The Cambridge Companion to the Cello and Reader’s Guide to Music; and 31 entries in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Her edition of the music of the noted 19th-century London cellist Robert Lindley will be published by Bärenreiter this fall.