by

Published June 10, 2019

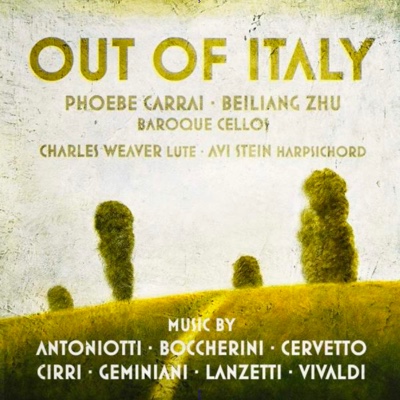

Out of Italy

Phoebe Carrai and Beiliang Zhu, baroque cellos; Charles Weaver, lute; Avi Stein, harpsichord;

Avie AV2394

By Andrew J. Sammut

This album’s title references the peripatetic lives of the composers heard here: Italian virtuosos of the 18th century who left “the home of music” and traveled Europe to seek better opportunities. Yet Phoebe Carrai and Beiliang Zhu are the real story. They have created a rich, extraordinarily performed program of Baroque and early Classical works — with “just” cellos.

Most of the names and music on this disc may be unfamiliar even to seasoned ears, beginning with Milanese violinist-cellist Giorgio Antoniotto and his Sonata in G, Op. 1, No. 8. The piece demonstrates craftsmanship with a passionate edge. It also showcases the vocalized tone and rhetorically-shaped phrases that Carrai and Zhu bring to the entire recital. Zhu is the soloist, yet her lead and Carrai’s cello in the continuo meld into brief but mellifluous duettini in the opening Adagio, and Carrai plays downright lyrical bass lines in the third movement.

Most of the names and music on this disc may be unfamiliar even to seasoned ears, beginning with Milanese violinist-cellist Giorgio Antoniotto and his Sonata in G, Op. 1, No. 8. The piece demonstrates craftsmanship with a passionate edge. It also showcases the vocalized tone and rhetorically-shaped phrases that Carrai and Zhu bring to the entire recital. Zhu is the soloist, yet her lead and Carrai’s cello in the continuo meld into brief but mellifluous duettini in the opening Adagio, and Carrai plays downright lyrical bass lines in the third movement.

Giacobbe Cervetto’s Divertimento in G, Op. 4, No. 1, for two unaccompanied cellos begins with an arioso dialogue and effectively differentiated sounds: Carrai slightly darker and broader, Zhu lighter and a bit more incisive. A beautiful but ominous Andantino follows; effects such as scraping lines over smoother strokes and flute-like harmonics give the fingerboards all the colors of a mixing board. It finishes with a courtly Tempo comodo bordering on comic, especially with a nervous middle section interrupting all the pleasantries.

Both cellists’ imaginative treatment of texture, articulation, and dynamics avoids the sewing-machine monotony that occasionally mars string displays from the period. For example, Neapolitan Salvatore Lanzetti was one of the most technically innovative cellists of the early 18th century. Yet Carrai digs into the moody Adagio cantabile of his Sonata in A minor, Op. 1, No. 5, with just the right amount of tension, and the central Allegro’s short repeated phrases come off as addictively agitated.

Carrai and Zhu, again unaccompanied, trade the lead on Giovanni Battista Cirri’s Duetto in G, Op. 8, No. 3. Starting with a genial Galant theme, the Allegro ma poco elegantly builds into a friendly game of one-upmanship. The virtuosity is all the more impressive given the players’ sense of classical restraint. The fussy buffa exchange in the concluding Rondo, contrasted with a noble yet still understated middle section, is played with laser focus as well as humor.

The album also features surprising selections by the better-known names: Carrai by turns plaintive, rocketing, comforting, and playful in Geminiani’s Sonata in F, Op. 5, No. 5; Zhu interpreting Vivaldi’s Corellian Sonata No. 6 in B flat, RV 46, with a lush voice, folksy lilt, and nimble passagi (plus a beautiful spot when the continuo drops out and the two cellos “sing” together).

Boccherini’s Sonata in C, G17, is in the composer’s usual easygoing style, with a mysterious second movement and gracefully oscillating close. Another work for two cellos without continuo, it features a more definite division between Zhu’s lead and Carrai’s accompaniment. Like Cirri’s piece, other players might pass this off as simply light, polite stuff. These musicians approach it with conviction and without overwhelming its sweetness.

Harpsichordist Avi Stein and lutenist Charles Weaver provide sturdy rhythmic and harmonic support that keeps the focus on the cellists. Stein plays a golden-toned instrument that is appropriately dry for these Italian works yet never merely sprinkles chords. In the second movement of Vivaldi’ sonata, the lute’s strums and plucks have the impact of a snare drum. The acoustics at Battell Chapel in Norfolk, CT, and the engineering capture it all, up-close and personal.

Zhu studied with Carrai at Juilliard. They combine the warmth of the best student-teacher relationships with the power and sensitivity of two peers. This disc is music making at its purest.

Andrew J. Sammut has written about early music and hot jazz for All About Jazz, Boston Classical Review, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, Early Music America and the IAJRC Journal as well as his own blog. He lives in Cambridge, MA.