by Andrew J. Sammut

Published February 17, 2020

On Paganini’s Trail…H. W. Ernst and More. Edson Scheid, violin. Centaur CRC 3735

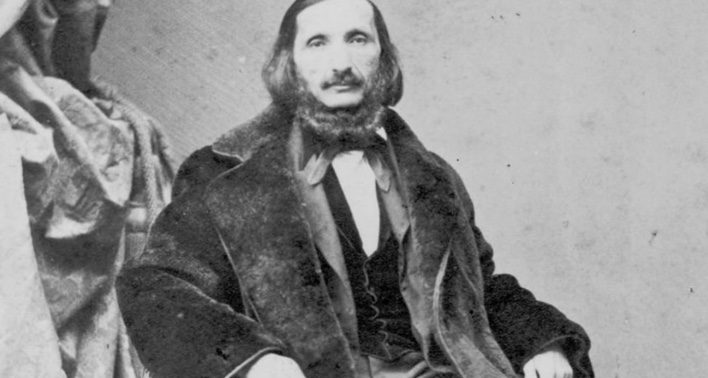

Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst was considered a successor to Niccolò Paganini before Paganini was even gone. The Czech violinist (1812-1865) made a similar career as a traveling virtuoso across Europe. Admired by Berlioz, Chopin, Joachim, and Paganini himself, among others, Ernst also had a superhuman technique plus an expressive power that some said actually outmatched the Italian master.

Ernst wrote some of the most difficult works in the violin repertoire, music that reveals formal and emotional variety beside all the flash, including the unaccompanied Six Polyphonic Studies and the Grand Caprice sur “Le Roi des Aulnes” heard on this release. This may be the first recording of these works on a period instrument. If not, it’s one of very few.

Ernst wrote some of the most difficult works in the violin repertoire, music that reveals formal and emotional variety beside all the flash, including the unaccompanied Six Polyphonic Studies and the Grand Caprice sur “Le Roi des Aulnes” heard on this release. This may be the first recording of these works on a period instrument. If not, it’s one of very few.

Brazilian-born, New York City-based violinist and American Baroque Orchestra concertmaster Edson Scheid plays a mid-19th-century French violin (maker unknown) with a modern bridge, tailpiece, and chinrest as well as gut strings and no shoulder rest. He explains over email that this is closer to the instrument a violinist would have played when the Studies were published. Scheid’s liner notes and performances point to obvious excitement at employing a period instrument and historical practices for this music.

Scheid handles multi-stops, bariolage, alternate hand pizzicato, and other feats with the assurance needed to turn display into music. In the fifth study, breakneck runs and sudden octave skips alternate with murmuring low-register phrases against ecstatic soprano commentary. The fantasia-like introduction to the sixth study maintains lyrical focus amid thick chording. Its fourth variation — pairing left hand plucks with rising and falling arpeggios — takes on an earnest charm.

Listeners used to more incisive, faster interpretations may at first be surprised by Scheid’s modest pacing. He takes his time through these works, letting them breathe without losing sight of execution or musicality, and setting up a unique miniature narrative for each study. His freedom with portamento adds warmth and character, for example, in the smirking first study and its leaping theme. Restrained vibrato clarifies polyphonic lines: The relaxed third study features a rich viola-like accompaniment, which then takes the lead and becomes its own longing tale of recollection.

There are fewer moments for Scheid to simply sing through his instrument, which is just the nature of these selections, but he still demonstrates plenty of personality. In the Grand Caprice (a solo-violin recasting of Schubert’s “Erlkönig” lied), Scheid becomes a one-person quartet with insistent bassetto strokes, mid-register chords, and an ominously choreographed melody. Once again, rather than slashing attacks or over-heated drama, Scheid’s expansive approach gives the well-known work an ominous feel.

At the other end of the emotional spectrum, in Paganini’s Introduction and Variations in G major on “Nel cor più non mi sento,” humorous echo effects and trills show good comedic timing. That is, of course, alongside shredding through ricochet bowing and other pyrotechnics.

Scheid also extracts a range of timbral possibilities from these showpieces. Gut strings open up a range of colors. His rapid double-plucking comes off like a well-tuned set of timpani. Raspy harmonics shows he’s unafraid to make a less-than-beautiful sound for the sake of textural exploration. At several points, he also pulls out rich, boxy strums like an acoustic bass guitar.

In Scheid’s own solo-violin arrangement of the third movement of Mozart’s Duo for Violin and Viola, K.423, the underlying viola part is still there, now stacked right next to the lead for an earthy texture. Scheid clearly has fun turning Mozart’s refined upbeat rondo into a winding chase with playful pauses and a range of articulations. It’s a logical finish for this program, with Scheid carrying on the tradition of transcription and expressive virtuosity.

Andrew J. Sammut has written about Baroque music and hot jazz for All About Jazz, Boston Classical Review, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, Early Music America, the IAJRC Journal, and his own blog. He also works as a freelance copy editor and writer and lives in Cambridge, MA, with his wife and dog.