by Karen Cook

Published May 30, 2022

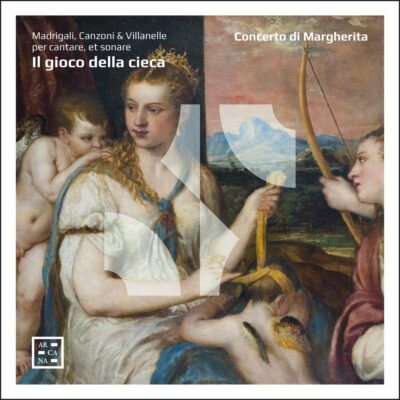

Il gioco della cieca: madrigali, canzoni & villanelle per cantare, et sonare. Concerto di Margherita. Arcana A498

Musical tastes changed significantly over the course of the 16th century and into the 17th. More and more, musical taste was centered in the idea of expressive power. Both sacred and secular vocal genres saw a rise in the number of voice parts, allowing composers to contrast different groups and textures with one another over the course of a piece, while performers also began to accompany themselves on a host of instruments. All of these strategies were designed to heighten the alignment between music, text, and expressivity, creating in music whatever affect or emotional state the text called for.

No ensemble held such renown for their singing and self-accompaniment in this new stile concertato fashion, as this new CD’s liner notes explain, as the Concerto delle dame, a largely female consort based in Ferrara. But few ensembles today model themselves vocally on this famous group or accompany themselves in such spirited fashion.

No ensemble held such renown for their singing and self-accompaniment in this new stile concertato fashion, as this new CD’s liner notes explain, as the Concerto delle dame, a largely female consort based in Ferrara. But few ensembles today model themselves vocally on this famous group or accompany themselves in such spirited fashion.

Enter the Concerto di Margherita, an exciting new ensemble named after Margherita Gonzaga, Duchess of Ferrara, the erstwhile ensemble’s patron. The new Concerto was formed when its members were students together at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, and while this recording—their debut—was recorded in 2019, it is only now being released.

The recording includes an array of madrigals, arias, and villanelles for two to five voices, the earliest from the Flemish composer Giaches de Wert (1535-1593), the latest from the Austro-Italian Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger (1580-1651). Interspersed throughout are a handful of all-instrumental works—canzons by Giovanni Gabrieli and Girolamo Frescobaldi, and modern instrumental variations on two of the vocal works. The quality of the vocal production throughout is top-notch, and it is matched by that of the instruments, which shine as much in their various accompanying roles as in the standalone instrumental works.

The 17th-century desire for contrast is certainly present here. The ensemble alternates voice types between pieces, such as having the lower voices in Kapsberger’s “Veri diletti qua giù non regnano” immediately follow the higher voices in his “S’io sospiro e s’io piango.” The internal contrasts in texture, tempo, and emotional affect in de Wert’s “Cara la vita mia” render it a true standout.

Other gems include the deliciously crunchy “O belli e vaghi pizzi” by Andrea Gabrieli and the concluding five-part “O prima gioventù de l’anno,” again by de Wert, especially the slower, stretchy lower part of the opening “O primavera, gioventù de l’anno” leading into the angelic higher-voiced seconda parte, “O dolcezz’ amarissime d’amore.”

The ensemble has chosen a very reverberant, live atmosphere that usually serves them well, especially in amplifying the lowest registers of their strings, but in a rare few cases, such as Sigismondo d’India’s “Occhi belli, occhi sereni,” it is just a bit overpowering. Overall, though, it is a fantastic debut from a very promising ensemble, and if they have plans to continue to explore this kind of concerted repertory, we will be the richer for it.