by Emily Thelen

Published October 16, 2023

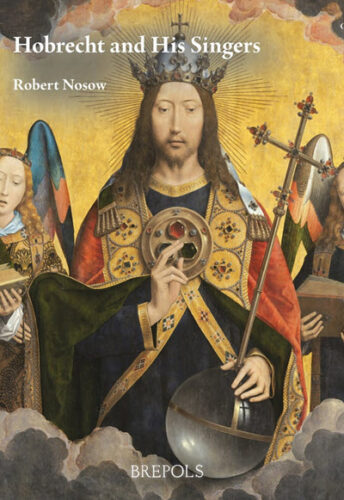

Hobrecht and His Singers by Robert Nosow. Brepols Publishers, 2022. 321 pages.

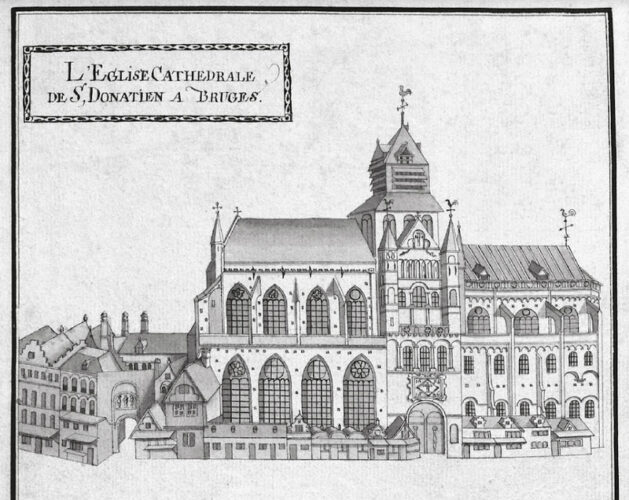

Reading Robert Nosow’s Hobrecht and His Singers is a bit like stepping into a Pieter Bruegel painting. We see a scene of tremendous detail, from the ordinary and mundane to the absurd and comic, and yet it all comes together to give a glimpse of early modern Flemish life. Using an abundance of archival documents full of delightful detail and colorful antics, Nosow weaves together a narrative of the Collegiate Church of Saint Donatian in the Belgian city of Bruges and the lives of its singers at the end of the 15th century.

Destroyed during the French Revolution, St. Donatian was once the most powerful ecclesiastical institution of Bruges, an international trading center, commercial hub, and important city for the Burgundian state. The church employed over one hundred canons, priests, musicians, and officials, including the famous composer Jacob Obrecht (1457/59 – 1505). (In his book, Nosow chose to use the spelling of the composer’s name that appears most frequently in historical records: Hobrecht.)

Through his meticulous examination of the church’s surviving records, the author portrays its singers as real people, faced with the practical and financial challenges of making a living in the context of a volatile political climate.

The accounts describe — and perhaps disproportionately represent — disagreements in the choir and disciplinary action taken against the singers. Such problems can of course be found throughout the long history of church choirs, up to the present day. The documented host of complaints against the singers of St. Donatian include poor attendance at liturgical services, wandering through the church during services, stealing a city official’s staff, derisive criticism of the choir director, “continual mockery and chatter committed in the choir,” and being in general “extremely lazy, disobedient, and wholly incapable.” One particularly troublesome singer was cited for punching the high contratenor in the mouth, causing an “effusion of blood.” The disciplinary actions taken against the singers ranged from withholding daily wages to brief imprisonments in the church’s own prison to outright dismissal. The canons frequently resorted to public humiliation — forcing the singers to stand at the eagle lectern for many days at a time.

Two important themes emerge from Nosow’s rendering of musical life at St. Donatian: first, how deeply embedded the church and the musicians were in civic affairs, and secondly, how important the singing was not only for the liturgy but also for the church’s civic function.

An incident involving Jacob Obrecht and four other singers during the May Fairs of 1501 illustrates both of these points. The city’s annual procession with the relic of the Holy Blood — which still takes place today — was the most momentous civic occasion of the year in late medieval Bruges and led to the May Fairs, significant for both trade and merriment. Members of the Burgundian-Habsburg court had attended, and the city of Bruges underwrote most of the liturgical celebrations. During the procession and the fairs following it, Obrecht and four of his singers were accused of “various and numerous mockeries, confabulations, and also other entirely insufferable transgressions and offenses.”

The poor behavior of the singers reflected badly not only on the church but on the city as well, in front of the Burgundian-Habsburg court no less. Obrecht was subsequently expelled from his position as choir director, effectively banished from the city, and serious punishments were given to the other singers. On other significant feasts, singers were disciplined severely because their absence from the evening service meant that polyphony could not be sung, making the church look bad in front of the civic officials who regularly attended. The singers, moreover, were often absent from their daily positions because they took temporary higher paying jobs; competition for polyphonic singers was a constant problem for the canons.

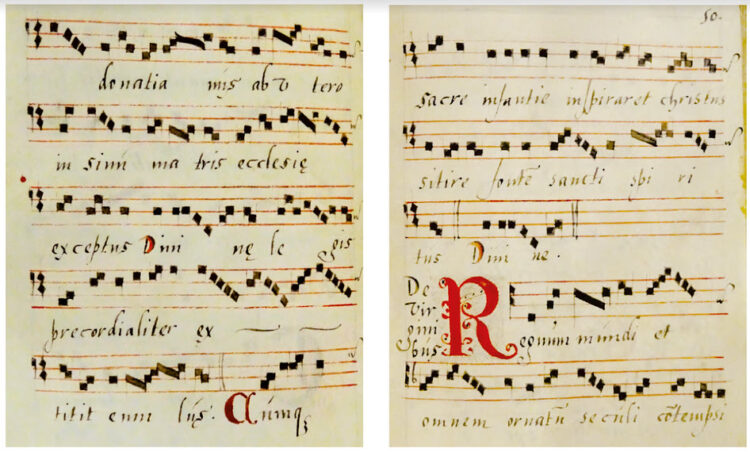

Finally, Nosow fills in the daily life and duties of Obrecht’s role as the church’s succentor or master of the choirboys. He suggests how Obrecht might have found time and purpose for composing and places several compositions in the context of civic networks and church affairs. For example, Nosow presents new documentation surrounding Obrecht’s arrest and imprisonment in 1490 to put forth a new hypothesis about the origins of his Missa de Sancto Donatiano and it being a reflection on both his own time in prison and the fall of Bruges to Maximilian’s troops.

This book will be interesting for scholars of both music and history as well as early-music lovers. Specialists will appreciate its dense text to the fullest, especially the large number of transcriptions of the archival documents in Latin and Dutch included at the end. However, the first section of the book is a good introduction to the complex structure of a collegiate church at that time, in regards to finances and personnel, and demonstrates how much negotiation went into obtaining the best singers. Nosow’s painstaking research as an independent scholar of original documents not available online is impressive and illustrates the various applications of archival work and how necessary it still is.

Emily Thelen is an editor and musicologist who writes about music and liturgy in the Low Countries. She held a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Leuven, Belgium and has published on the Seven Sorrows Confraternity of Brussels. Her writing for EMA includes a book review of John A. Rice’s Saint Cecilia in the Renaissance: The Emergence of a Musical Icon.