by Elizabeth Rouget

Published November 14, 2022

Listening to the Fur Trade: Soundways and Music in the British North American Fur Trade, 1760-1840 by Daniel Robert Laxer. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022. 304 pages.

Understanding the role of music and sound in cross-cultural partnerships—largely from the European settlers’ perspective.

The portrayal of “the Great North” by the celebrated 1920s Canadian painters of the Group of Seven gives us an impression of Canada as wild, barren, and silent. Vast landscapes of dense forest, harsh rocks, and snow-blanketed earth furnish an image devoid of life, community, and song.

But the Great North wasn’t silent at all. In his recent book Listening to the Fur Trade, Daniel Robert Laxer gives voice to the European fur traders and Indigenous peoples, among them the Anishinaabe and the Haudenosaunee, who inhabited this land together between 1760 and 1840, and fills the sonic void with soundways of the past. The narratives he recounts highlight the cross-cultural encounters of the British North American fur trade and provide a better understanding of the role played by music and sound in forging partnerships. The book is an elaboration of Laxer’s 2015 dissertation, with the same title, from the University of Toronto.

But the Great North wasn’t silent at all. In his recent book Listening to the Fur Trade, Daniel Robert Laxer gives voice to the European fur traders and Indigenous peoples, among them the Anishinaabe and the Haudenosaunee, who inhabited this land together between 1760 and 1840, and fills the sonic void with soundways of the past. The narratives he recounts highlight the cross-cultural encounters of the British North American fur trade and provide a better understanding of the role played by music and sound in forging partnerships. The book is an elaboration of Laxer’s 2015 dissertation, with the same title, from the University of Toronto.

The book spans the fur trade’s musical heyday in the mid-18th century to its artistic demise in the 1820s under George Simpson, the Hudson Bay Company’s ruthlessly budget-conscious governor. Laxer’s study begins by considering non-musical sounds, emphasizing the role of gunpowder and firearms as a constant source of percussion in the landscape. Muskets were traded between the European fur traders and Indigenous peoples and were often used as a method of communication over long distances. Gunshot blasts signaled arrivals and departures of traders and were later incorporated as key elements of ceremonial rituals celebrated by Indigenous communities.

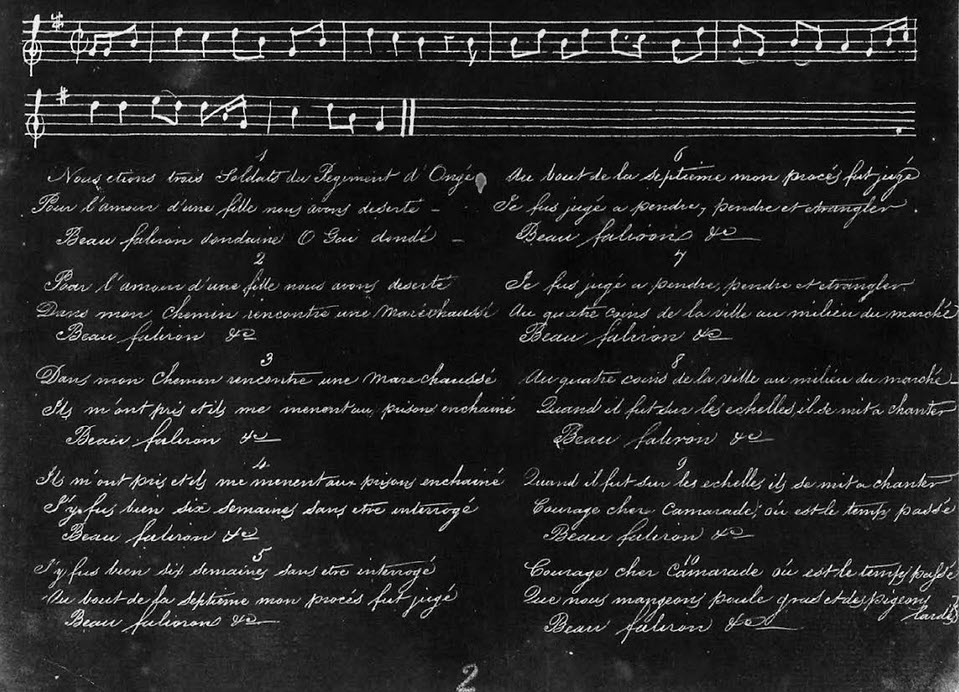

Voyagers who traveled between the trading posts paddled canoes along river routes and portaged over land. While doing so, they sang chansons d’aviron to synchronize paddle strokes and keep spirits up on the long and often food-bare journeys. Influenced by 17th-century French songs, these tunes were in laisse form (verse with rhyming couplets and chorus) and were improvised with additional text to extend the duration of singing. Several well-known songs were often stitched together to form a continuous accompaniment to the voyagers’ paddling day. Some records of the voyages and written lyrics remain, although they constitute only a shell of the performance practice of this tradition.

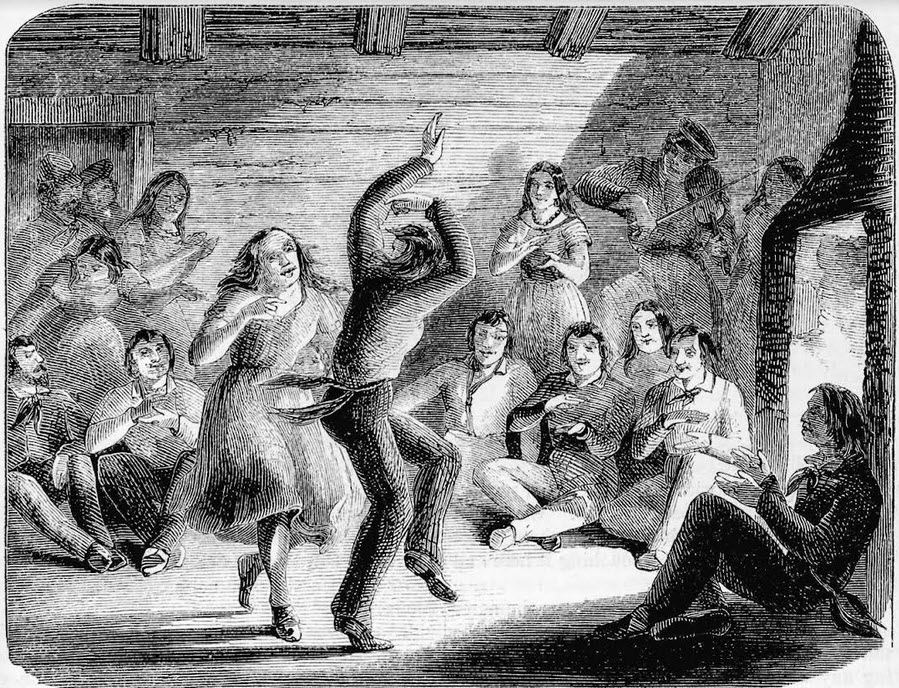

The growth of the fur trade also led to the appearance of military instruments and drums on fort inventory lists, and these instruments proliferated in social rituals as trading posts became more established. While it was difficult to transport large instruments along the paddling routes, there are accounts of fiddles, bagpipes, and drums entertaining groups at balls and holiday festivities. These social gatherings played a key role in fostering peaceful and reciprocal relationships between the European traders and local Indigenous communities where, typically, the local First Nation or American Indians trapped and skinned the pelts and traded them to the British, who sent them home to fashionable European customers.

Each party relied on the other for food, arms, knowledge of the land, and, in many cases, help in life threatening situations. Amid this need for mutual trust, music and dance helped bridge the wide gulf between different languages and customs, providing a much-needed avenue for communication. Laxer recounts many instances where a common ground was achieved after each faction sang a song as an offering.

Descriptions of these encounters, as recounted by the author, are solely from the perspective of the European settlers and do not afford the alternative perspective of the Indigenous voices. In relying exclusively on material sources, Laxer acknowledges the limited and partial contextual understanding they provide. He thus attempts to reconstruct a more inclusive soundscape by imagining all the sounds—gunshots, singing, cries, bells, instruments, etc.—that could have populated these cross-cultural spaces.

Listening to the Fur Trade is a useful source for primary material, and the author must be commended for his depth in archival research. Of the eight chapters in his book, numbers six (“Paddling Songs;” “Chansons D’aviron”) and seven (“Indigenous Hunting and Healing Songs”) are the highlights, demonstrating Laxer’s polished prose and thorough investigation. Other chapters rely purely on archival sources and lack critical perspective and discussion. Daniel Robert Laxer’s diligent, if sometimes repetitive, presentation of primary source accounts reminds the reader of the kind of community storytelling that passes timeworn lore down the generations. Full value is given to the written records of the tradition, guiding the reader to discover for themselves the echo of voices past.

Elizabeth Rouget is a doctoral candidate at Princeton University studying the import of French opera and dance to North America at the time of the French Revolution. Hailing from southern Ontario, she is fascinated by early modern musical accounts of home.