by Thomas May

Published May 16, 2022

Opera was born of the tantalizing premise that what had been lost to history could be regenerated through an act of creative imagination. So it seems peculiarly fitting that one of the foundational works of the art should inspire a similar effort.

Seattle-based Pacific MusicWorks, for their upcoming season finale this week (May 20 and 21), will give the world premiere of a new musical completion of the finale scene that appeared at the end of the originally published libretto for Claudio Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo.

Combining sung and danced performance, this alternate ending is the work of Stephen Stubbs, the renowned lutenist, conductor, and the founder and artistic director of Pacific MusicWorks. Not least, he’s also the longstanding co-director of Boston Early Music Festival. Stubbs and his chamber ensemble will be joined by a quartet of sopranos (Danielle Reutter-Harrah, Tess Altiveros, Arwen Myers, and Teresa Wakim) and three female dancers who will present choreography by Baroque dance specialist Anna Mansbridge.

The program, titled Wayward Sisters, is Stubb’s final scene for L’Orfeo plus freshly theatricalized presentations of works by such contemporaries as Luigi Rossi and Emilio de’ Cavalieri and a recent composition by Karen P. Thomas.

“A question that has been buzzing in the back of my mind for many years,” Stubbs asks about L’Orfeo in a recent conversation, “Why is the ending in the libretto [originally printed in 1607] different from the ending in the score [published two years later]? The plastered-on lieto fine or happy ending that we usually see never felt completely satisfying to me. I’ve always been interested in the libretto’s original ending, which takes place at the highest pitch of Orfeo’s moment of madness.”

L’Orfeo famously stands out as an exception in terms of the relative state of completeness in which this favola in musica has survived—in stark contrast to the immediate successor, L’Arianna, and the other lost Monteverdi operas.

But the mystery of the “double ending” remains unresolved. “We are unusually well supplied with information about L’Orfeo,” Stubbs explains. “Many other pieces of the time were lost or only have sketchy information or no original score. But in the case of L’Orfeo, we have both the printed libretto and the printed score, and both were carefully overseen by their creators.”

A quick recap. Having successfully traveled to the Underworld, Orpheus has just lost his beloved Euridice a second time after succumbing to the temptation to look back. Returned to the Earth, he vents his renewed grief and rage in a lament, praising the incomparable Euridice while forswearing the love of all other women as “worthless.” His father Apollo suddenly arrives to calm Orpheus, reassuring him with the invitation to ascend with him into the heavens, where he will be consoled by a celestial vision of Euridice.

The split between the two endings occurs at the end of our hero’s powerful lament. Stubbs regards the lament as the equivalent of a “mad scene” that, with compelling musico-dramatic logic, sets up the tragic conclusion initially envisioned by Monteverdi’s librettist Alessandro Striggio. In their opera, Orfeo’s final words in the fifth act, as printed in 1607, shift the topic to the arrival of the Bacchantes (Striggio uses the Latin-derived Baccanti, not the Greek Menadi). Orfeo hears a “hostile band” of these female worshippers of Bacchus approaching and withdraws “at the hateful sight,” departing from the scene.

The Bacchantes suddenly appear onstage, first as a chorus and alternately split among the group and one or two singers. They offer hymns to Bacchus but also goad each other with the urge to get revenge for Orfeo’s offense against women and, by implication, against Bacchus. (The connection has to do with Orfeo’s renunciation of physical love in his lament—Eros being central to the realm of Bacchus/Dionysus in Neoplatonic philosophy, an important layer in the Renaissance attempt to “resurrect” ancient Greek tragedy.)

Combining praise and a call for blood, the Bacchantes end with the phrase del tuo divin furore (“with your divine fury”). In Stubbs’s new musical setting of this scene, this culminates in the so-called moresca (“Moorish dance”), the instrumental movement that is usually performed as a celebratory dance at the end of the later, Apollonian, deus ex machina version. Stubbs believes the moresca is a remnant from the original version, citing the work of the German musicologist Silke Leopold.

“Her theory is that this is meant to be a wild dance, during which the Baccanti actually put hands on Orfeo and do the deed—maybe offstage? This is where they go on the attack and slay the hero,” says Stubbs. He draws comparisons with another contemporary treatment of the myth in Stefano Landi’s La morte d’Orfeo (1619), which Stubbs recorded with his ensemble Tragicomedia during an earlier, Europe-based period of his career. Landi’s strange retelling unfolds as a kind of sequel that shows the aftermath of the enraged Bacchantes’ attack: slain and dismembered, the hero again ends up in the Underworld and tries to be reunited with Euridice, but she no longer remembers him.

“Most people have assumed that the version of the score printed in 1609 is what the audience heard on opening night in 1607 in Mantua,” according to Stubbs. “But that can’t be the case. I’m convinced that what they heard and saw at that premiere was the version with the Baccanti ending as printed in the libretto they were given at the event. The fact that we have the words but don’t have the music just seemed a ripe plum to pick.”

Stubbs took advantage of the sudden opening in his schedule during the pandemic lockdown to prepare his new version. He’s undertaken similar projects in the past, such as supplying an ending chorus to Handel’s first opera Almira. “A tantalizing two pages are extant, but the rest was ripped out by Telemann to write his own ending when he did a revival,” he explains. Nor is a completion of the “other” ending to L’Orfeo without precedent: in 2019, Iván Fischer presented an alternative of his own with his opera company.

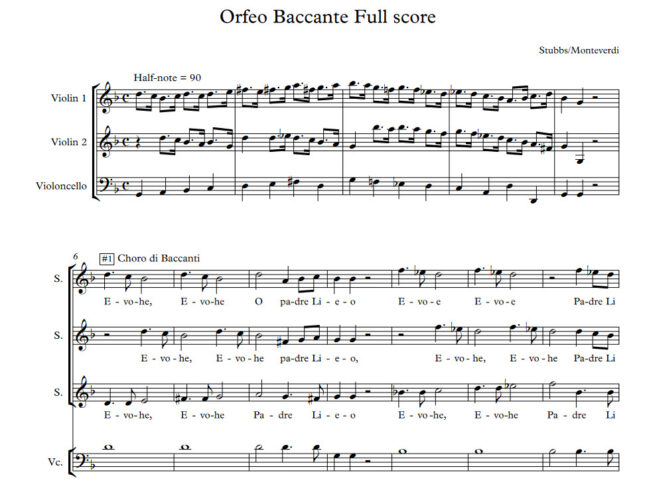

Stubbs uses three soprano voices for the Bacchantes plus an instrumental contingent of two violins and continuo. Mirroring the singers will be a trio of dancers in Anna Mansbridge’s new choreography for the Bacchantes. Stubbs includes a bit of quotation from earlier in the score: the march to the temple for the wedding ceremony, which is set in the minor.

But for the most part, says Stubbs, he has written new music: “It’s my response to the words. I don’t think any composer can ever feel good about just trying to be a ventriloquist, singing in someone else’s voice. I used some harmonies I’m pretty sure Monteverdi wouldn’t have used.” At the same time, he adds, his overall approach to word setting follows “the Monteverdian sense.”

The continuo ensemble (Baroque guitar, harp, viola da gamba, and harpsichord) plays an especially important role. Renowned for his innovative approach to the realization of continuo, Stubbs defines “a good continuo team” as able to draw on the whole “emotional palette of the continuo instruments” by understanding what each instrument can contribute specifically to the mix. “We all know how to use that in the context of Monteverdi.”

Fresh approaches to continuo are an important front in the early-new music alignment as well. Stubbs invited the composer and choral conductor Karen P. Thomas, director of Seattle Pro Musica, to write a piece for three female voices and continuo for the original iteration of his Wayward Sisters program in 2013, looking for a parallel to Mansbridge’s original choreographic language fashioned from Renaissance and Baroque dance idioms. Thomas responded by setting a 17th-century text by Andrew Marvell, Doubleheart, which will also be performed alongside the new L’Orfeo ending.

“I knew that this would require her to think in terms of writing for basso continuo (essentially a harmonic framework) rather than individual ‘parts’ for the instruments,” Stubbs says. This approach to writing a continuo line means that “you’re not dictating to the players but are giving them an invitation to use their own musicality and sense of harmony to supply what’s needed.”

“It is my deep conviction that a musical culture is at its most vibrant when performing musicians also feel empowered or even necessitated to create new music—whether by composition or improvisation. This idea of what it means to be a musician would have seemed obvious to every composer on this program, from Monteverdi to Thomas.”

Thomas May is a writer, critic, educator, and translator. He is the English-language editor for the Lucerne Festival and contributes to the New York Times, Seattle Times, Musical America, and many other publications. He also blogs about the arts at memeteria.com.