“Women-actors [are] all notorious impudent, prostituted Strumpets” — William Prynne, Histrio-Mastix 1633

These infamous words from Prynne’s lengthy critique of theatricality exemplify the actress as whore trope that has plagued professional female entertainers since antiquity. The Restoration singer-actresses Nell Gwyn and Mary “Moll” Davis had remarkably successful careers on the public stage and were also vehemently vilified for their romantic relationships with Charles II. While most singer-actresses of the period were criticized for perceived immorality, Gwyn and Davis stand out due to the ways in which their musical performances ultimately resulted in an elevation of their social statuses. These extraordinary women rose to fame during a period of sweeping social, legal, and scientific change on issues that directly impacted gender roles in all levels of English society.

Legally Taking the Public Stage

“And we do likewise permit and give leave that all the women’s parts to be acted in either of the said two companies for the time to come may be performed by women…” — Patent from Charles II to Thomas Killigrew, 25 April 1662

Upon returning from exile in 1660, Charles II ushered in an English era known for its secularization, theatricality, debauchery, and gambling. In addition to re-opening the public theaters, which had been closed during the austere years of the Interregnum, he officially granted Englishwomen the legal right to appear on the public stage. Actresses had appeared with growing frequency elsewhere in Western Europe during the 16th century, but in the English public theaters, men and young boys played all female roles until the 1660s.

Although English feminism was on the horizon, women on stage sparked numerous social and religious debates. Some decried the singer-actresses’ immorality, while others fetishized, courted, and even assaulted them. Unfortunately, the women’s own perspectives are lost to history, but we can gain tremendous insight into their professional accomplishments from the plays and songs they performed. The predominant form of public entertainment in Restoration England was spoken stage plays interspersed with incidental songs and instrumental music by composers such as Pelham Humfrey, John Banister, Henry Purcell, and John Eccles.

From the outset, women on the English stage were highly sexualized and subjected to having their personal lives enmeshed with their public personae. The first known public play to include women was a re-creation of Shakespeare’s Othello in late 1660. Thomas Jordan’s newly written prologue for the Restoration production included the following:

“Do you not twitter Gentlemen?

I know you will be censuring, do’t fairly though;

’Tis possible a vertuous woman may abhor all sorts of looseness, and yet play;

Play on the Stage, where all eyes are upon her,

Shall we count that a crime France calls an honour?”

Within the year, actresses had solidified their position on stage, and all the gentleman were twittering.

Moll Davis and Nell Gwyn ~ The King’s Ladies

“‘My Lodging it is on the Cold Ground, &c.’ She perform’d that so Charmingly, that not long after, it Rais’d her from her Bed on the Cold Ground, to a Bed Royal.” — John Downes, Roscius Anglicanus, 1708

Moll Davis (c. 1650-1708) joined the Duke’s Theatre Company managed by William Davenant in the early 1660s, quickly becoming popular for her singing, dancing, and acting. She had at least nine named roles during her tenure, but the one that purportedly changed her life was Celania, the mad shepherdess in Davenant’s 1664 The Rivals. Lovesick for Philander, she sang “My Lodging it is on the Cold Ground,” a performance Downes credited for her move from working-class actress to King’s mistress. Davis is reported to have met Charles II in 1667, and by mid-1668, she left the stage to be his mistress.

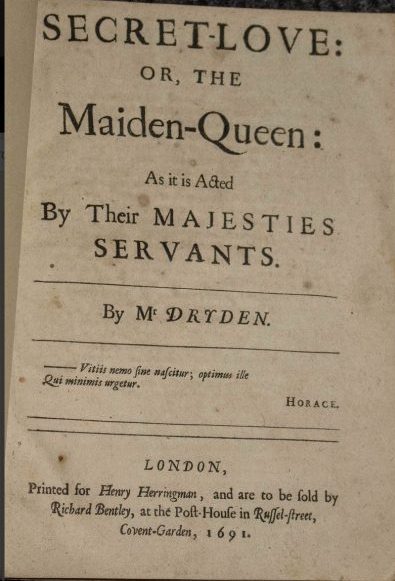

Nell Gwyn’s rags-to-riches story of a life transformed from the slums of London to the royal bedchamber has captivated public imagination for centuries. Her theater career began in 1663 as an “orange girl” selling concessions to audiences in the pit, and she joined the King’s Company as an actress for the 1664-65 season. Gwyn (1642/50-1687) played at least 10 named roles before formally leaving the stage in 1669 as the King’s mistress, a relationship that continued until his death in 1685. She was particularly beloved in comedies, as noted by Pepys in his recollection of her performance of Florimel in John Dryden’s Secret Love: or, The Maiden Queen:

“ so great [a] performance of a comical part was never, I believe, in the world before as Nell do this, both as a mad girle, then most and best of all when she comes in like a young gallant; and hath the motions and carriage of a spark the most that ever I saw any man have. It makes me, I confess, admire her.” — Diary of Samuel Pepys, 2 March 1666/67

Gwyn sang a parody of “My lodging it is on the Cold Ground” in 1667 as part of a comic mad spoof in James Howard’s All Mistaken, or, The Mad Couple. This was a mere three years after Davis’s premiere of the song, which had become quite popular. The tune for both the original song and its parody is somewhat spuriously attributed to Matthew Locke, and both tune and text of the original song appeared frequently in various collections beginning in 1665 and continuing well into the 18th century. Moreover, the text was incorporated into a longer broadside ballad, suggesting that it became a significant facet of London’s cultural collective conscious. Given early modern England’s increasing fascination with madness as well as the obsession with the women who personified it on stage through song, it is easy to see how Davis and Gwyn’s performances of this mad song elevated their popularity and even enticed the King.

From Beloved Singer-Actresses to Depraved Whores

Hard by Pell-Mell, lives a wench cal’d Nell,

King Charles the second he kept her,

She hath got a trick to handle his…[prick]

But never lays hands on his Scepter.

All matters of State, from her Soul she does hate,

And leave[s] to the Pollitick Bitches,

The Whore’s in the right, for ’tis her delight,

To be scratching just where it Itches.

Both Davis and Gwyn were the brunt of derogatory satires, such as the anonymous lampoon above. Pepys frequently praised Davis for her performances, yet when she became romantically involved with the King, she was instantaneously transformed from “the pretty girle, that sang and danced so well” to an “impertinent slut.” Pepys recorded the following account from his wife’s perspective:

“Mis Davis, who is the most impertinent slut…in the world; and the more, now the King do show her countenance; and is reckoned his mistress, even to the scorne of the whole world” — Diary of Samuel Pepys, 14 January 1667/68

The extreme backlash against Gwyn and Davis was certainly at least partially rooted in moral debates of the time concerning marriage, sexuality, and gender roles. But it seems there is something more insidious underlying the criticism leveraged at these two women — their social class. Davis’s parental lineage is uncertain, but she was likely the illegitimate daughter of the third Earl of Berkshire or his brother. Likewise, Gwyn’s mother worked in a notorious bawdyhouse in the slums of London. Neither Gwyn nor Davis was an “acceptable” addition to life at the court. They were working class women; their actress status rendered them servants. Moreover, their children fathered by Charles II received titles and inheritances. If the grandsons of a low-class brothel madam could become an Earl and a Lord, perhaps the very notion of an absolute monarchy and social stratification could be at stake.

Savvy Businesswomen or Innocent Victims?

Just as opinions about the Restoration singer-actresses were wildly varied from titillation to pejorative scrutiny, contemporary readings of these women are also mixed. Some portray the women as innocent victims of egregious power dynamics — surely the affections of the King were not something Gwyn or Davis could have refused, regardless of their personal feelings. And given the rigid social structure, becoming a mistress to a wealthy man was the only way for an actress to lift herself out of the working class and create a better life for her children.

Revisionist theorists, on the other hand, draw attention to the various forms of agency the Restoration singer-actresses had, despite the aforementioned power imbalances and limited accessibility to upward social mobility.

What stands out as most striking are the ways in which Gwyn and Davis’s musical and theatrical prowess elevated their social status. Their performances of “My Lodging it is on the Cold Ground” and its parody were received with tremendous critical acclaim. For the first time in England’s history, poor women with questionable parentage were able to publicly and professionally sing their way into a position of social prominence. “My Lodging it is on the Cold Ground,” brought to life by Gwyn and Davis, became as much a part of Restoration London culture as the vitriolic satires about the women’s “whorish” inclinations.

More than 350 years have elapsed since women were granted legal permission to perform publicly in England, yet the actress as whore stereotype persists in dramatic criticism today. In the summer of 2019, for example, Manuel Brug described a performance of Offenbach’s Orphée aux enfers at the Salzburg Festival as full of “fat women in tight corsets [who] keep spreading their legs.” This is, of course, one extreme example, but professional women remain more likely to be described by their appearance or relationship status in critical reviews than their male counterparts. One need only read articles about pianist Yuja Wang for examples.

As we look forward with great anticipation to the moment when musicians are once again able to retake the public stage in a post-pandemic time, perhaps we might endeavor to modify the ways in which women and other marginalized performers are reviewed. After all, it would be great if a music historian 350 years from now was able to write about how our generation influenced significant changes in the language we use to describe others.

Paula Maust, DMA, is a performer-scholar based in Baltimore, MD. She teaches music theory, music history, harpsichord, and organ at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and The Johns Hopkins University. Dedicated to edgy concert programming connecting historical people and events to contemporary social issues, she curates new programs each season as a co-director of Burning River Baroque and Musica Spira. Her research focuses on expanding the canon as well as the reception history of early modern women on the stage, particularly those who were described as being both musically talented and physically, morally, or racially ugly. More info can be found at www.paulamaust.com.