by Gail O’Neill

Published April 4, 2022

After a pandemic hiatus, Opera Lafayette returns to in-person performances with The Era of Marie-Antoinette Rediscovered, stories on love, loss, and splendor from 18th-century France and, significantly, France’s long-suffering colonies. Musicians and historians often speak of the glories of the early-music repertoire and the culture in which it thrived, but rarely delve into politics and economics to ask who paid for that great art, architecture, and music.

The Era of Marie-Antoinette Rediscovered attempts a more three-dimensional perspective from the age of revolution. The series will cover fully staged productions in Washington D.C. and New York, plus salons, seminars, children’s programming, and a book club. There’s also a residency/workshop in New Mexico.

Inspired by the woman who remains an icon and a cautionary tale more than 200 years after her death, the smartly connected series will, at its core, shed light on Marie-Antoinette’s extraordinary education in music and dance, her early embrace of opéra comique, and her legacy as a champion of modern composers in pre-Revolutionary France.

“The mythologies of Marie-Antoinette are well known,” says violinist and conductor Ryan Brown, the founder and artistic director of Opera Lafayette. “We wanted to get at some things that might not have been said about that era or her patronage of music.”

Opera Lafayette will be in residence at the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation of New Mexico this May. Programming will include discussions and online seminars and culminate in a free workshop performance of the opera Silvain—just ahead of the production’s premiere, in June, at the Kennedy Center in Washington and El Museo del Barrio in New York.

Shortly after her arrival in France, Marie-Antoinette requested a performance of Silvain. André Grétry and Jean-François Marmontel’s 1770 opera of family conflict and reconciliation flirted with a scandalous proposition: the rights of peasants to use land owned by nobles. Marie-Antoinette’s appreciation of any narrative that challenged royal status was, of course, ironic given her place in the monarchy. But Silvain was an equally surprising choice because it mirrored tensions on the ground in French colonies like Saint-Domingue (modern day Haiti), where Enlightenment philosophies were in direct opposition to the human-rights atrocities being committed against enslaved people on sugar, coffee, and tobacco plantations.

Opera Lafayette’s production of Silvain will be set in a mid-19th century American Southwest—where land-rights conflict began two centuries ago, just after French entrepreneurs acquired land from the Mexican government and allowed settlers to cultivate vast tracks. Those conflicts—who owns the land?—persist today.

The musical culture of ancient régime France and people of the Caribbean—the enslaved, formerly enslaved, and free peoples—were a reflection of the inherent contradictions and complications of the unsustainable institution of slavery. Likewise, a free woman of African descent named Minette was the embodiment of these competing realities. An anomaly, she was a star singer who performed in theaters that catered to white colonialists in the capital city of Port-au-Prince in the 1780s.

Concert Spirituel aux Caraïbes, an orchestral concert with vocal soloists and ensemble, will explore Minette’s contributions to opéra comique on Saint-Domingue. The program will be conducted by Pedro Memelsdorff, who is also a scholar working on Minette’s life and repertoire.

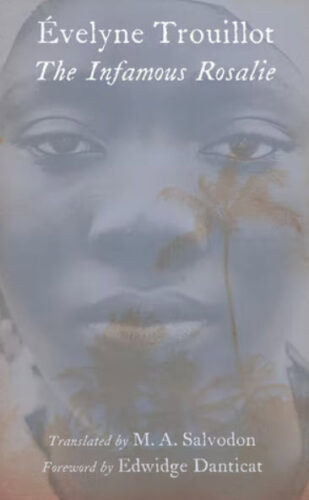

In an effort to give audiences a sense of what life was like for most people on Saint-Domingue, as opposed to a mono-focus from the perspectives of a privileged minority, scholars Kaiama L. Glover and Laurent Dubois will lead an online book group on The Infamous Rosalie. The 2013 novel, written by Évelyn Trouillot, explores themes of slavery, resistance, and motherhood. Glover, a prize-winning translator of several works of Haitian prose fiction and professor of French and Africana Studies at Barnard College, hopes readers will gain a better sense of the societies that helped shape the music in Concert Spirituel aux Caraïbes.

In an effort to give audiences a sense of what life was like for most people on Saint-Domingue, as opposed to a mono-focus from the perspectives of a privileged minority, scholars Kaiama L. Glover and Laurent Dubois will lead an online book group on The Infamous Rosalie. The 2013 novel, written by Évelyn Trouillot, explores themes of slavery, resistance, and motherhood. Glover, a prize-winning translator of several works of Haitian prose fiction and professor of French and Africana Studies at Barnard College, hopes readers will gain a better sense of the societies that helped shape the music in Concert Spirituel aux Caraïbes.

Saint-Domingue, which produced 40 percent of all sugar and 60 percent of all coffee consumed in Europe, “was the most economically rich colony in the whole of the Americas,” says Glover. “The average life span for an enslaved person there was just three years because planters determined that working the enslaved to death and replacing them with fresh imports was more cost-efficient than providing the necessary conditions for human beings to survive and reproduce. Évelyn’s novel gives a glimpse into the lives of less-celebrated figures in the age of revolution, where notions of freedom and human rights are in the air. These are the conversations being had at [white colonists’] dinner tables where enslaved people are serving food and drink.”

The Marie-Antoinette Salon Series, a three-part seminar curated and hosted by Julia Doe, will challenge Marie-Antoinette’s reputation for frivolity by contextualizing her place among the Habsburgs, an exceptionally artistic royal family. (Spoiler: She never said “Let them eat cake.”) An accomplished harpist, she was trained by celebrated composers like Christoph Willibald Gluck and Johann Adolf Hasse in preparation for her role as France’s future queen. Her serious and long-ranging musical pursuits continued after assuming her place within the French court. In time, her modern sensibilities and love of the opéra comique aesthetic spilled into the ceremonial repertory of the Bourbon Court and helped finally supplant old works, such as Lully operas, from the court of Louis XIV.

“Marie-Antoinette’s musical patronage includes sponsorship of little-known works by Grétry and support for concerts in Paris—where her attendance could be a major make-or-break moment for a composer—and her penchant for hosting private concerts,” says Doe. “After the birth of each of her children, she had a stage erected in her private apartment so performances could keep going in her convalescence.”

Guest scholar Caroline Weber will contribute to the salon series by discussing Marie-Antoinette’s musical endeavors within the broader question of her status as taste-maker in a variety of media, from fashion and the decorative arts to garden design and music. And Rebecca Geoffroy-Schwinden will cover the transition from pre-Revolutionary music making among women all the way through the Napoleonic period, when women’s rights were even more curtailed than they had been in the 18th century.

The Musical Salon of Marie-Antoinette, featuring Sandrine Chatron playing a historical harp from Marie-Antoinette’s era, will bring the listener into her salon at Versailles to hear arias and chamber works of Gluck, the Caribbean-born Chevalier de Saint Georges, and Phillip Hinner, a survivor of the ill-fated colony Kourou in Guinea, among others.

In addition, thinking about the theme in today’s context, the series will screen Titixe—an intimate mosaic of the last harvest of a Mexican family, in a country that has forsaken its rural origins—by the award-winning filmmaker Tania Hernández Velasco. Tying together several threads of this Marie-Antoinette project, Velasco is also stage director for Silvain.

Finally, as Opera Lafayette seeks to cultivate future fans, a series of educational lessons titled Opera Starts with Oh! will introduce young audiences to the magic of opera under the guidance of teaching artist Omar Cruz.

A lot of French culture arrived in the United States in the 1790s as French colonists fled Saint-Domingue following the Haitian Revolution. Silvain was the first opera staged in New Orleans in 1796, where it was a hit, before being produced in Charleston and other cities on the East Coast.

Now, as tensions that precipitated the French Revolution expose the same fault lines in today’s societies—borne of economic, racial, and class inequities—one could argue that a genre of early musical theater, which represented the dynamism of 18th century France, is more prescient than passé.

Gail O’Neill is an Atlanta-based writer and producer. She is an ArtsATL.org editor-at-large, and hosts and co-produces Collective Knowledge, a conversational series that’s broadcast on THEA Network, and frequently moderates author talks for the Atlanta History Center.