by Patricia Ann Neely

Published February 12, 2023

In Honor of Black History Month

It began with a Facebook conversation between a fellow alum of Vassar College and me and a CBS Sunday Morning segment on the origin of fudge:

Whether it was being the first woman to drive an automobile alone transcontinentally, suffrage, eugenics, or chocolate—our early alumna were always at the forefront among women. Whether I agree with their endeavors or not, I am proud of all of them.—E.R.W.

We come from a long line of rebels! Making fudge over an open flame in the dorms, holding suffragette meetings in the cemetery behind then Student’s [Building], or taking over Main Building in 1969 in support of Black Studies, we continue to impact lives and make history.—P.A.N.

Thanks to a recipe for making fudge passed on to a Vassar student in 1888 (a failed attempt at making chocolate caramels), the reputation of the Vassar female rebel was lent strength to prosper and grow through the centuries, and thus were born the female ambassadors who put creativity and tenacity to work in concert with academic pursuits to their advantage in the professional world into which they were launched.

This is the cloth from which I was cut and the legacy that I inherited from an institution that has historically discriminated against Blacks. While the college has been called out for its racist history, the knowledge has become a catalyst for discussion and a call to action for revealing the whole truth as to how and why.

Still, my Black classmate in the above-mentioned Facebook thread and I are able to gain courage from elements of the college’s history and draw strength from some of the tainted history. One of the most important queries is why and how those early Black students, who had an opportunity to be educated at the institution through three centuries and several decades, have been able to thrive, achieve success, and solve challenges in their professional careers.

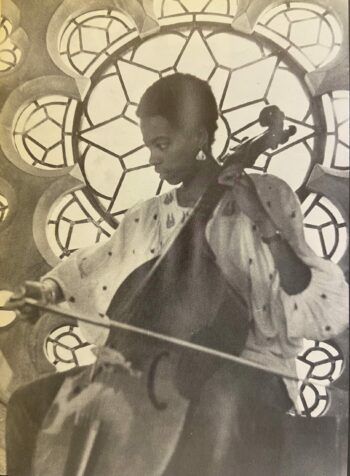

The opportunity for me to dream, create, and follow a path that I expected would hold me in good stead was, frankly, fraught with challenges. What do you do when you have been taught to believe in your creative gift both at an arts high school and in college during the most important years of development, only to be discouraged in overt and subtle ways in the profession?

Instead of, “show us what you can do,” it became telling me in so many different ways “what I would never be able to do,” and I remember every one of them as they were and remain now very hurtful remarks. The comments ranged from “you’ll never be a professional viol player because you never played cello,” to “can we borrow your viol for a rehearsal for someone traveling from out of town to New York, I figured you wouldn’t need it anyway,” to “I just don’t see you as a professional,” to “you’re not a viol player…. Do you own an instrument?” One of the most unforgettable experiences occurred at a music school where I was employed as both an administrator and faculty member in medieval music. When it was announced that I wanted to mount Hildegard von Bingen’s “Ordo virtutem,” I was called into a meeting with the dean and several colleagues where I was cross-examined as to how I was going to prepare such a project—after I had spent three years working with the medieval ensemble Sequentia in Europe.

That experience in Europe wasn’t even enough to validate my expertise. I had done all the preparation months before the production, influenced by my work with Sequentia. However, all of the people involved in the school ensemble on the technical and support team abandoned me. Nevertheless, I channeled those Vassar fudge makers and collegiate suffragettes who, interestingly, would never have given me equal respect as a fellow scholar. With tenacity, I succeeded in mounting the production with co-director Drew Minter. The production was a success, and it received a wonderful review by James Oestreich in The New York Times. I questioned whether I would have been put through this humiliating and utterly disrespectful experience if I had been white. But, at the time, I had no comparable experience with which to consider, and I did not have other Black colleagues with whom to reach out. These are just the tip of the iceberg in terms of the distractions that have permeated my journey as a black professional in the field of early music.

In 2019, when Karin Brookes, then executive director of EMA, asked me to work with her on creating a task force to examine the issue of diversity, equity, inclusion, and the lack thereof in our field, I found myself feeling a sense of optimism for my own career as well as for young and emerging artists in early music.

In my presentation on the history of Blacks in the arts at the Indiana University Historical Performance Conference that year, I stressed that the work we propose to do must be a priority and managed on a regular basis; otherwise, goals will not be achieved. Unfortunately, we have watched this new movement flounder, and attention wax and wane according to media intrusion and internal battles—which is sad.

I have tried to do my best as an individual who owes so much to LaGuardia High School of Music and Art and Vassar College for lending me support and shaping me as a musician so that I can continue to believe in myself, even if some in the profession have not been as kind. There are those in the profession who have believed in me, and I want all those colleagues to know that your words of encouragement have really meant a great deal to me. They have sustained me through many challenges along the way. I take comfort now in giving back to those who have made it possible for me to get, if only, a fraction as far as I would have liked at this stage in my career.

Thanks to the grant I received from the Viola da Gamba Society of America, it’s been a rewarding experience to bring the viol to both institutions (LaGuardia and Vassar) where I was once an eager student. I am relishing the sheer enthusiasm these students exhibit on their journey toward learning to play the viol. My spirits have been lifted once again and I hope that my little contribution will become a priority, to be sustained and managed in perpetuity.

Patricia Ann Neely is managing director and viol player with Abendmusik, New York’s Period Instrument String Ensemble. She is on Early Music America’s Board of Directors.