By Guy Fishman

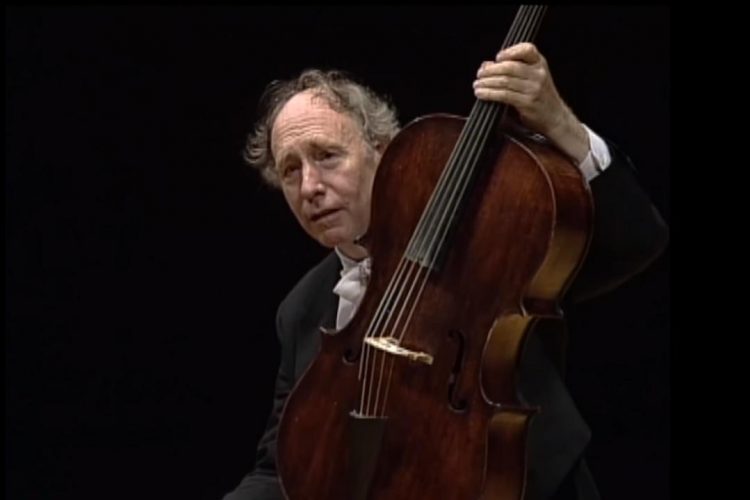

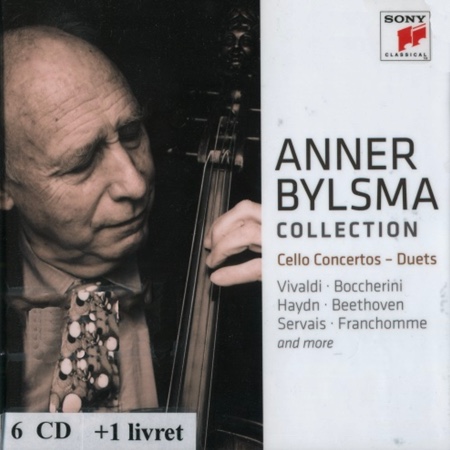

I play early music on period instruments because of the great Dutch cellist Anner Bylsma, who died July 25 at the age of 85. When I was 14, I entered the classical music section of a Tower Records store where Bylsma’s recent release of arrangements of music for unaccompanied flute and violin by J.S. Bach, performed on his son’s 7/8-sized cello tuned like a violin, was being played. I didn’t pay much attention to it until Bylsma hit the final note of the prelude to the E major Partita, BWV 1006. It ended a driven but, as I realized much later, subtly nuanced and very “spoken” performance. It seemed the energy stored by what had preceded the note was fully released by it: powerfully, beautifully, emphatically, and most notably to me, without a hint of vibrato. I had never heard anything like it; it shocked and captivated me. I grabbed a copy and bought it. Anner changed my life, and would do so again.

I listened to the recording every day for months. I studied Bylsma’s liner notes and in pre-Google days searched for anything about the cellist I could find. A few years later, I was able to hear him play three Bach suites at the Walter Reade Theater, a woefully dry acoustic situated at Lincoln Center in Manhattan. He addressed the audience to explain why he was sitting on a “throne,” as he called it — a podium barely wider than a chair, regularly used by concerto soloists (“It sounds better, even without an endpin.”). During the fifth suite, he tuned his “a-turned-g” string while sustaining it in a cadence. I knew I needed to play for him. After getting his autograph, I asked if he took students. He said, “I have left school,” in a way that seemed as though he was recently matriculated in a degree program but decided to drop out.

It took some time, but I got my chance to study with Bylsma after all. During doctoral studies at New England Conservatory, I was awarded a Fulbright fellowship in Amsterdam, and because Bylsma was not affiliated with a university, I took private lessons at his home next to the Vondelpark. Lessons began with tea and biscuits in the kitchen, over which discussion was had on a variety of topics, musical and not. We then moved upstairs and worked for two hours in a room dominated by a massive library of first editions and copies sent by distant libraries, collected over a lifetime and organized in folders (“I’m very proud of my system.”). When I could take in no more, we would return to the kitchen to listen to some recordings while eating an aged Gouda and drinking Calvados, his favorite spirit. This weekly wonder of an experience lasted about three hours; when I said I needed to split lessons in two so that I could absorb more easily, Anner agreed to two weekly lessons, but what was presumably to last 1-1/2 hours turned into two 2-1/2 hour lessons. Anner had quite a bit to say about a great many things.

By the time I moved to Amsterdam, I had already released a CD and had steady work with the Handel and Haydn Society and Boston Baroque. In my arrogance, I arrived with a copy of Bylsma’s book, Bach, the Fencing Master, annotated with my various oppositions to the arguments he made in it. It didn’t matter. Anner made certain I didn’t waste too much of my time arguing by completely disarming me with an infectious wit and charm, delivered by an almost mesmerizing storytelling ability. Within a couple of weeks, I was converted; by the time I left, I wanted to be just like him.

The level of inquiry and erudition was intoxicating. There was not only what he had read, in either Dutch, German, French, or English, but the conclusions and extrapolations he created, usually presented as a scene that would give a South Bank director pleasure in creating, or a remembrance of some colorful event from his past, or just an entertaining analogy. “At the end of your bow, right before you change direction, you must slip on a banana peel”; “This note should be connected to the next by just the thinnest strand of spittle”; “My aunt Viola once heard vibrato. She exclaimed, ‘Why, I would NEVER do that!!!’ So here, in this measure, think of my aunt Viola.”

But there was plenty of practical, technical direction. Anner was entirely aware of his place in the early-music world and how other cellists viewed him (while in Amsterdam, I heard Janos Starker give a speech in which he said, “The world’s greatest baroque cellist lives right here in Amsterdam.” There was no doubt as to whom he meant.) But he did not regard these as “baroque cello” lessons, and I understood why Hidemi Suzuki told me that Bylsma wouldn’t teach him baroque cello when he studied with him. Bylsma began playing on a cello fitted with gut strings and never gave them up. He won the 1959 Pablo Casals Competition using them; he was principal cellist of the Concertgebouw Orchestra playing on them. He recorded Debussy, Schubert, Hindemith, Messiaen, and Shostakovich on them. When his colleague Tibor de Machula asked him why he played on such old-fashioned strings, he replied that, surely, steel strings — having come around in a more global way in the 1920s and 30s — were by the 1970s themselves old-fashioned, and that everyone should use gut. Certainly the repertoire was Baroque — he assigned me works by Domenico Gabrielli, Antonio Vivaldi, and, of course, the suites for unaccompanied cello by J.S. Bach, although there was also Haydn, Romberg, Beethoven, Schumann, and Popper. But the element that is a highlight difference between standard and baroque instruments — gut strings — was not discussed.

What was discussed, and the only bit of equipment Bylsma cared deeply about, was the bow. I started on my way to understanding the variety of weight and emphasis created by a limitless vocabulary of articulation that I had unknowingly encountered at Tower Records when Anner — who was not performing publicly any more — began demonstrating his use of the bow. The nimbleness of the fingers controlled not only an uncannily speech-like performance (“Is this music sung, like someone speaking with his mouth open? Or is it spoken?”), but also every imaginable sounding point on the string and therefore an ability to articulate a thought with sound density rather than pressure.

What was discussed, and the only bit of equipment Bylsma cared deeply about, was the bow. I started on my way to understanding the variety of weight and emphasis created by a limitless vocabulary of articulation that I had unknowingly encountered at Tower Records when Anner — who was not performing publicly any more — began demonstrating his use of the bow. The nimbleness of the fingers controlled not only an uncannily speech-like performance (“Is this music sung, like someone speaking with his mouth open? Or is it spoken?”), but also every imaginable sounding point on the string and therefore an ability to articulate a thought with sound density rather than pressure.

Anner’s wife, the superb violinist Vera Beths, once told me as an aside, “Anner has the best bow arm in the world.” I accept this statement as fact. This is easy to do because when I asked Anner why he used his Peccatte bow for his second recording of the Bach suites and his Bouman baroque bow for Haydn concerti, he answered, “What your ear hears, your bow must do.” There was perhaps no more important lesson to be learned. What is evident in the numerous tributes to Anner that over the last week have appeared in print and online is that the music world mourns the loss of the imagination that wielded that bow and created that sweet tone with which the music was spoken. It was driven by an indefatigable curiosity that Anner followed at any given moment, living fully in that moment, sometimes talking through it and suddenly asking a seemingly unrelated question as a new direction was suggested, or breaking out in laughter, his bushy eyebrows angling impossibly, as he did so.

Many thought Anner was a provocateur, but that is not who I experienced; he was fully committed to the journeys his curiosity and imagination took him on, and did not mind inviting us along, through performances, writings, recordings, and lessons, the last paired with a good Calva. I still have a list of questions I wanted to ask him, things he pointed to in lessons that hinted at one such journey or another. Now he’s taken a journey on which I cannot come, so, as I did after that Bach recital I once heard, I’ll have to wait.

Guy Fishman is principal cellist of the Handel and Haydn Society.