by Laura Stanfield Prichard

Published October 12, 2020

Throughout the Classical and Romantic periods, the humble accordion and its simpler cousin, the concertina, were important parlor, chamber, and accompanying instruments. The earliest forms of the accordion were inspired by the 1777 introduction of the Chinese free-reed sheng (bowl mouth organ) into Europe by Père Amiot, a Jesuit missionary in Qing China. Amiot entertained Beijing listeners by playing harpsichord versions of Rameau’s music, including Les sauvages (later part of Les Indes galantes). His introduction of the sheng set off an era of experimentation in free-reed instruments such as Anton Haeckel’s Physharmonika, a bellows-operated reed organ (Vienna, patented 1818), and Friedrich Buschmann’s mouthblown “Handäoline” (Berlin, patented 1822). Two of Haeckel’s instruments from 1825 can be seen in the Vienna Technical Museum. The Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg holds Europe’s largest collection of early German free-reed instruments, accordions, and harmonicas.

The accordion’s name, from the German word Akkord (chord), first appears in an 1829 Viennese patent by the Armenian inventor Cyrillus Demian (1772-1849). Demian’s description emphasized the “new” aspect of playing whole chords on one side of the instrument (one or two keys in early models) in contrast to concertina construction (with melody buttons on each side of the bellows, and no chordal keys). The National Music Museum in Vermillion, SD, has a large collection of accordions by Hohner and notable 19th-century German makers: Its one-of-a-kind diatonic button accordion by the Berlin maker J. Pomm is a custom experimental model built for Constantin Wettering, who worked as a professional musician in New York City and Chicago in the late 1850s. It plays in eight keys, with 70 treble key levers and buttons for the right hand.

The Leipzig maker Anton Zuleger produced a line of small Tanzbär 28-note “player accordions” with rolls of punched paper, made to play prerecorded music while allowing the player to add additional notes. This instrument was manufactured from 1870-1925.

European Styles

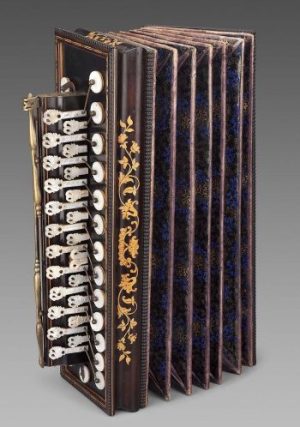

Each country in Europe developed its own title for the accordion in the early 19th century: The terms accordéon (French), acordéon (Spanish), fisarmonica (Italian), garmonika [гармоника] or bayan [баян] (Russian), and Ziehharmonika or Akkordeon (German) all appear by 1830. The most successful early Romantic manufacturers of the diatonic accordion were Charles Buffet (Belgium), Jean-Baptiste-Napoléon Fourneaux (France), and Constant Busson (Brevet, Paris, France). They produced instruments of lasting visual beauty and quiet, mellow tone, with costly ivory and mother-of-pearl inlays in rosewood, brass reeds, and 10-12 treble keys balanced by two bass buttons. In the 1830s, Paris became a major center of accordion production, which flourished until the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71.

A lavishly decorated instrument by Alexandre Pere & Fils (Met: 1998.70) follows a model by Demian of 1831. Its case has foliate designs in blue, green, pink, and white enamel-like mastic with brass and tortoiseshell inlays. The 24 mother-of-pearl keys each operate two notes (one on push and a second on pull). The multifold bellows are lined with embossed silver foil bearing green flocking.

The only other surviving “Paris accordions perfectionnes,” or “perfected” accordion with a second button row for the accidentals, is also in New York at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (G. Kaneguissert, c.1860, Met: 2005.317). In addition to the two-row keyboard, this instrument has five basses and two registers of different reeds to produce different timbres. In contrast to accordions made in Vienna and Germany, the lowest note speaks at suction.

American collections holding examples of Busson’s accordions (with mother-of-pearl keys and brass reeds) include Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts (MFA: 1998.100) and New York’s Met. (Met: 2002.108a).

The London music dealer Keith, Prowse & Co. sold small French accordions made of mahogany (c1830, Met: 2003.379a) and ebonized wood (c1840, MFA: 17.1946); the Boston instrument was owned by Francis W. Galpin until 1916.

The MFA also has two c.1860 rosewood French accordions, one with elaborately carved mother-of-pearl keys and one with a complete instruction booklet (MFA: 1975.391 and 2006.817), and an American watercolor (c.1850) by American John P. Soule (1828-1904) showing a lady holding a French Busson accordion; the innovative wove paper for this portrait is watermarked 1838 from Whatman’s paper mill in Kent, England (MFA: 52.1558).

Similar instruments appear in late Meiji-period Japanese prints (1880s-1910s) and postcards (1890s-1910s) featuring young girls and professional geishas with French accordions (MFA: 2002.17873 and 2002.17945).

The National Music Museum also holds a beautiful 1860 chromatic accordéon-orgue, or harmoniflute, by the maker Mayer-Marix in Paris. It has a three-octave piano-style keyboard (f-f) with bone natural keys and ebony accidental keys. Later models of this instrument were fitted to a stand with a pedal for operating the bellows.

Russia also has a strong free-reed tradition, with a variety of accordions and mouth organs. Among them is the small 19th-century cherepashka, combining the setup of the very early Viennese accordions with five to seven keys and bass, chord, and air-release buttons. An accordion in the collection at the Met — a semiklapanka (c.1870, Met: 89.4.1308) — is pitched in A (sounding g-sharp). It has seven brass keys, with the lowest note sounding at suction.

Early Concertinas

The English concertina was developed by Charles Wheatstone in London in the mid-1820s. It is a six-sided instrument with 64 keys, alternating melody notes between the hands, with pressure and suction giving the same note on two different reeds. Both hands nominally play the same 12 notes, but those played with the right hand sound an octave higher. With the chromatic range of a violin, English concertinas were intended for playing Classical music and became fashionable during the Victorian era.

Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts holds two British concertinas: an original Wheatstone with silver reeds and a paper bellows (London, c.1845, MFA: 2005.124) and a beautiful rosewood and green leather model produced by Cramer & Co. (London, c.1865, MFA: 17.1945).

New York’s Met has three Wheatstone concertinas, including a rare model from the 1830s (predating Wheatstone’s patent in 1844) and a duet concertina (c.1855, Met: 2003.381b). Wheatstone was not only a physicist and manufacturer but also carried on a publishing business. Soon after 1850, he published an instruction book for the duet concertina and 12 books of arrangements of popular music to promote the introduction of this model.

In 1829, Wheatstone also adapted his concertina mechanism into a luxury “mouth organ” called the symphonium, with solid silver or nickel silver reeds and ivory side buttons. The symphonium features two characteristics of his concertina: the same notes at pressure and suction, and alternative distribution of the diatonic tones to the right and left hand (C is for the right hand, D for the left, E for the right hand, etc.). The chromatic tones are the buttons of the outer row. The two groups of 12 buttons on each side produce a chromatic range from c1 to d3 (lacking d#1). The form of the instrument recalls a sheng without pipes. Boston’s MFA and New York’s Met hold rare examples (MFA: 1996.115 and Met: 89.4.2085).

Carl Uhling created the first German version of the concertina in 1834, splitting the right-hand system from Demian’s accordion between the two hands.

The New World

Accordions and concertinas were introduced to Latin America in the 19th century by German immigrants. Accordion-family instruments can be found in many South American traditions, including Brazil (sanfona), Colombia (valenato), and Argentina (bandoneón). In Mexico and the United States, the acordeón de botón (button accordion without keyboard for the right hand) is commonly used in tejano and norteño music. Together with the bajo sexto, the acordeón de botón forms the backbone of the norteño conjunto. Two early pioneers on the instrument were brothers Narcisco and Raul “El Ruco” Martinez. Modern mariachis and banda groups often include accordions.

Huapano tamaulipeco (haupango norteño, one of the main indigenous Mexican forms to be incorporated into música tejana) features the accordion and strengthens the music’s ethnic identity. Tex-Mex repertoire consists equally of these regional folk dances and of European forms like the waltz, polka, and schottische, all of which call for accordion.

The bandoneón (also spelled bandonion), named for the German instrument dealer Heinrich Band (1821-1860), was originally intended as an accompanying instrument for small-group religious and popular music, in contrast to the folk concertina in Germany. Around 1870, the instrument appeared in Argentina and was adopted into milonga and tango musics. By 1910, they were produced expressly for the Argentine and Uruguayan markets, with 25,000 shipping to Argentina in 1930 alone. The instrument is also popular in Lithuanian folk music. Aníbal Troilo and Ástor Piazzolla wrote extensively for the bandoneón in the 1930s-40s; the disruption of German manufacturing during World War II led to a rapid decline in the manufacture of bandoneóns, accordions, and harmonicas.

Sound Production

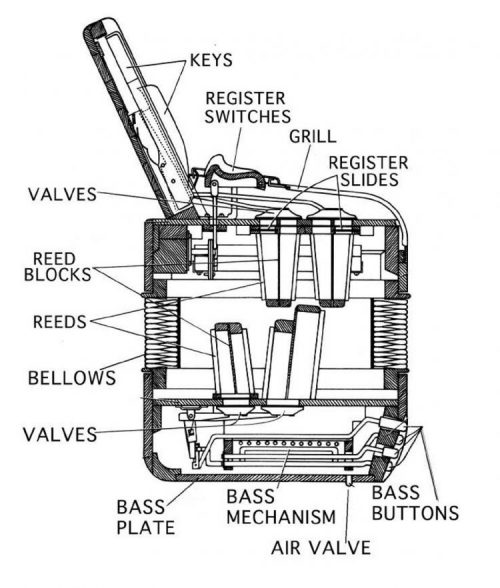

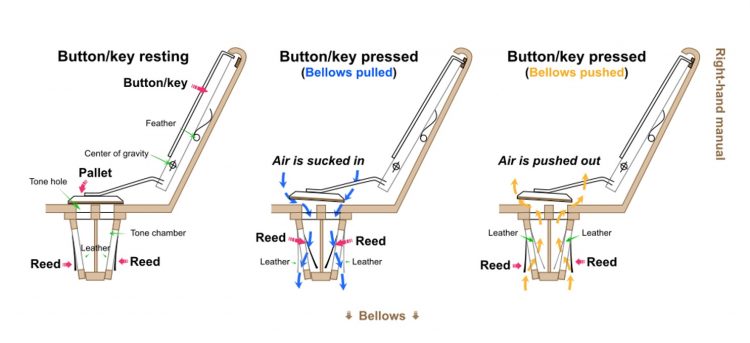

Accordions are free-reed instruments consisting of pairs of pre-tuned metal reeds (now usually steel) riveted to metal plates (now usually aluminum alloy). The plates are glued into a long reed-box projecting into the bellows, and reeds vibrate when air flows first over the reed, then through the slot on the plate. Air flowing in the opposite direction merely bends the reeds without vibrating them. For keyboard accordions, the left hand provides continuo (bass notes and chords), while the right adds melody and additional accompaniment. Most modern accordions also have leather or plastic flaps over the air slots to prevent loss of pressure.

Pairs of reeds can be duplicated and combined to create special effects such as octave doubling, tremolos, and “beating” of two closely tuned pitches. Register knobs and tabs on the outside move slides to engage or close additional ranks of reeds; these may be marked by a code of two horizontal lines with a dot signifying normal pitch or octave displacement, depending on its position.

Single-action Single-action instruments include the melodeon and the British chromatic accordion. Each melody button controls a pair of reeds (usually adjacent notes of a scale), so a scale can be accomplished with only four buttons (C, E, G on the press and D, F, A, B on the draw). This is the original action of the earliest accordions and is similar to that of mouth-blown harmonicas.

Single-action Single-action instruments include the melodeon and the British chromatic accordion. Each melody button controls a pair of reeds (usually adjacent notes of a scale), so a scale can be accomplished with only four buttons (C, E, G on the press and D, F, A, B on the draw). This is the original action of the earliest accordions and is similar to that of mouth-blown harmonicas.

Double action instruments such as the piano accordion and the Continental chromatic accordion favor music with a more complex, sweeping character, as each pair of reeds gives the same note, regardless of the way the bellows move.

Co-evolution of the Harmonica

Shortly after clockmaker Matthias Hohner (1833-1902) established his harmonica and accordion firm in 1857, he shipped some to American relatives. Hohner pioneered the use of machine-punched reed covers and mass-produced wooden combs. Harmonicas (free-reed adaptations of the accordion reed plate system) became popular on both sides of the Atlantic.

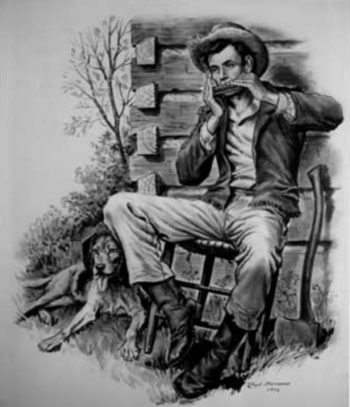

President Abraham Lincoln carried a harmonica in his pocket, and the instrument was played by Civil War soldiers and by frontiersmen such as Wyatt Earp and Billy the Kid. Hohner also produced steel reeds for accordions and helped to champion uniform tone through push-action bellows. Stimulated by players’ demands, the chromatic instrument with uniform tone became standard. By the beginning of the 20th century, the accordion’s bass keyboard had gradually developed to provide accompaniments in all keys, but it remained essentially a folk instrument, heard in cafés, dance halls, and music halls all over the world.

W. C. Handy recalled hearing train imitations played on the harmonica and accordion in the 1870s, and the Hohner Marine Band diatonic (in multiple keys) became one of the defining sounds of early blues style. It was usually played in second position, a fifth above the normal tuning (also called “cross harp” due to the dominant seventh chords generated). Wood-combed instruments were often dipped in water to improve the tone and “bendability” of notes in this style. By the 1920s, the accordion and harmonica industry produced more than 50 million instruments a year.

A music school for accordion teachers was established in Trossingen, Germany, in 1931; it became an official state academy in 1948 under the principalship of Hugo Herrmann (1896-1967), whose collection Sieben neue Spielmusiken (1927) was the first important musical composition for the solo accordion. The British College of Accordionists was founded in 1936 and provides a syllabus of accordion examinations still used today.

American design innovations have made the instrument more versatile: Reeds were usually riveted, bolted, or screwed in place, but All-American models from the 1940s were held in place by tension. The U.S. experienced an accordion and harmonica shortage during World War II since most manufacturers were based in Germany and Japan. Wood and metal were in short supply due to military demand, so Finn Magnus, a Dutch-American entrepreneur, developed molded-plastic versions.

Further Research

The Deutsches Harmonikamuseum (Trossingen) and the Alan G. Bates and Arne B. Larsen Collections at the National Music Museum (Vermillion, SD) hold the world’s largest accordion and harmonica collections. The Bates archive contains more than 1,500 instruments and 2,000 pieces of trade literature and ephemera, including antique sheet music. The American Accordionists’ Association just celebrated its 80th anniversary: It sponsors annual competitions, festivals, and master classes. Europe’s Confédération Internationale des Accordéonistes was founded in 1935: It sponsors international competitions including the “Coupe Mondiale.” In 1975, the CIA became the first instrument specific organization to be accepted into the International Music Council, which is the largest non-governmental division of UNESCO.

Dan Michael Worrall’s The Anglo-German Concertina: A Social History (2009) and Marion Jacobson’s Squeeze this! A cultural history of the accordion in America (Urbana: Illinois, 2007) examine the history of free-reed instruments. Accordion Crimes (historical fiction by Annie Proulx) traces the long odyssey of a button accordion, an instrument made by a Sicilian who immigrated to New Orleans in 1891 (NY: Simon & Schuster, 1996). Angelo Paul Ramunni of the New England Accordion Connection and Museum Company (Accordion Stories from the Heart, 2018) and Rob Howard (Vintage accordions : a pictorial history of the accordion, 2011) have published lavishly illustrated histories of the European accordion, and the Metropolitan Museum presented an exhibit on 19th-century free-reed instruments in Gallery 681 from 2005 to 2012.

Laura Stanfield Prichard’s 25 continuous years of college teaching (now in Boston) have focused on interdisciplinary cultural analysis of music, dance, and art history. She was assistant conductor of the San Francisco Symphony Chorus (1995-2003) and lectures regularly (now online) for Boston Baroque and the San Francisco Opera.