by Daniel Hathaway

Published July 19, 2021

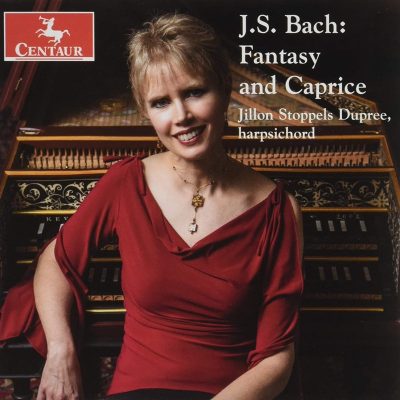

J.S. Bach: Fantasy and Caprice. Jillon Stoppels Dupree, harpsichord. Centaur Records CRC 2810.

Seattle-based harpsichordist Jillon Stoppels Dupree has recorded a delightful collection of favorite pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach that come under the broad category of fantasies and caprices — works that express the composer’s more impulsive side even while sometimes cast in the form of the fugue, or, in the case of BWV 992, the program sonata cultivated by Bach’s Leipzig predecessor, Johann Kuhnau.

Dupree plays a 2010 harpsichord by Berkeley, CA, builder John Phillips after a 1722 instrument by the Dresden maker Johann Heinrich Gräber, Sr. Recorded at a studio in Stockton, CA, the sound is lively and present, although artificial reverberation sometimes casts a hazy cloud around the music.

Dupree plays a 2010 harpsichord by Berkeley, CA, builder John Phillips after a 1722 instrument by the Dresden maker Johann Heinrich Gräber, Sr. Recorded at a studio in Stockton, CA, the sound is lively and present, although artificial reverberation sometimes casts a hazy cloud around the music.

A textbook example of the North German fantasia comes late in the playlist: the Toccata in d, BWV 913, which follows the rhetorical outline of similar works by Buxtehude that alternate fantastical, improvisatory sections with short fugues. Dupree skillfully paces its flights of fancy and plays its contrapuntal episodes with sprightly articulation.

The opening work, the famous Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue, BWV 903, expands on the format of BWV 913. Although it’s difficult to reproduce another individual’s improvisatory gestures, Dupree sensitively organizes Bach’s flourishes and gives fresh touches to his fugues, hurrying the tempo a bit here and there for expressive purposes.

The other works ring changes on the idea of musical impulsiveness. The three-movement Toccata in G, BWV 916, begins with a joyful Allegro, continuing with the nice contrast of an expressive Adagio, and concludes with an Allegro e presto to which Dupree contributes pointed articulations.

Also in three movements, the Sonata in d, BWV 964, boasts an aria-like Andante with a pulsing bass line and a final Allegro replete with echo effects and melismas that Dupree tosses off as the decorative gestures they are.

Toward the end of the album, the harpsichordist lightens the playlist with the Adagio in G, BWV 968, an arrangement of a transposed movement from the C-Major Violin Sonata that explores the rich bass register of the harpsichord, and a lovely, straightforward performance of what she describes as the “sweet, innocent” Prelude in G, BWV 902.

Bach never wrote another programmatic work like the valedictory Capriccio on the departure of a most beloved brother, BWV 992, and why this early suite is titled Capriccio is anybody’s guess. It makes a fun conclusion to this attractive album, and Dupree brings out its charms without making too much ado about the piece. A fugue on a posthorn call? Altogether delightful, just like the rest of this very personal collection.

Daniel Hathaway founded ClevelandClassical.com after three decades as music director at Cleveland’s Trinity Cathedral. He studied historical musicology at Harvard College and Princeton University, and orchestral conducting at Tanglewood, and team-teaches Music Criticism at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music.