by Andrew J. Sammut

Published August 23, 2021

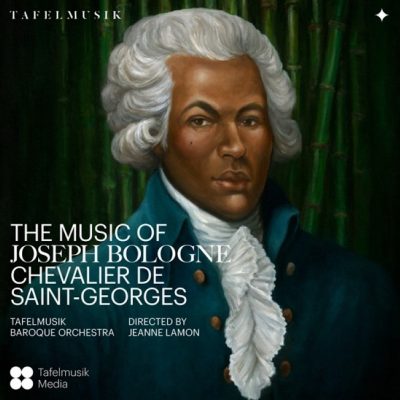

The Music of Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges. Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra (Jeanne Lamon, director). Tafelmusik Media TMK1032.

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, made “polymath” an understatement: In addition to his gifts as a composer, conductor, and violinist, he was (among many other accomplishments) a fencing champion, a respected and adored participant in Paris’s salons, a renowned equestrian, a military leader during the French Revolution, and an all-around leading light of the cultural, intellectual, and athletic spheres of the late 18th century.

Despite Saint-Georges’s talents and achievements, as a Black person born in the Caribbean to an enslaved woman and a plantation owner, France’s discriminatory legal codes barred him from fundamental rights, like marrying who he wanted, and embedded racism denied him positions and honors he had more than earned. The classical canon has, in turn, left little room for Saint-Georges and other composers disenfranchised in their time. More than 200 years after his death, this brilliant artist continues to impress and inspire even as he brings lingering inequities to the fore.

Despite Saint-Georges’s talents and achievements, as a Black person born in the Caribbean to an enslaved woman and a plantation owner, France’s discriminatory legal codes barred him from fundamental rights, like marrying who he wanted, and embedded racism denied him positions and honors he had more than earned. The classical canon has, in turn, left little room for Saint-Georges and other composers disenfranchised in their time. More than 200 years after his death, this brilliant artist continues to impress and inspire even as he brings lingering inequities to the fore.

Amid a long-overdue reckoning on race in the United States, Tafelmusik has reissued its 2003 album of Saint-Georges’s music with the goal of “properly centering the composer’s achievements,” now recognizing the original release’s title and artwork as part of an “erasure of Joseph Bologne and his legacy.”

Under the title The Music of Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, the recording includes a thoughtful new essay by Saint-Georges scholar-advocate and project consultant Marlon Daniel and an original portrait of Saint-Georges by Toronto painter Gordon Shadrach on its cover. It was released shortly before the death in June of Tafelmusik’s music director emerita, Jeanne Lamon, an early exponent of Saint-Georges’s music, who directed these performances and was thrilled to know this reissue was coming. The release is significant on many levels, including as another rare opportunity to appreciate this composer’s music.

These works display Saint-Georges’s formal proficiency and gift for catchy, characterful themes, like the four-repeated note motif in the overture to L’amant Anonyme’s Allegro presto or the ominously courtly minor-key interruption to the frivolity of the opera’s Contredanse. The central Andante of the overture shows off graceful contrapuntal writing, while the middle movement of the Symphony in G, Op. 11, No. 1, unfolds into a friendly, lightly accompanied Galant-era tune, which in turn comes off like a soloist at play, thanks to the tight, glistening sound of Tafelmusik’s strings. The symphony’s opening movement just keeps revving up, while the Allegro assai brings it to a boisterous conclusion.

The Violin Concerto in D, Op. 3, No. 1, offers a hint at Saint-Georges’s virtuosity. At nearly 11 minutes, its first movement is the longest track on the album. The solo parts flow from the orchestra’s melodies in exciting directions, and violinist Linda Melsted has the pace and space to unfurl Saint-Georges’s inventive lines. Lamon directs the succeeding Adagio to seize on its theatrical possibilities, while Saint-Georges’s writing showcases both the soloist’s and the ensemble’s sheen. The closing Rondeau adds more overtly virtuosic moments, but overall, this concerto and performance impress as much with lyricism and details as fast fingers and sweeping gestures.

Works from composers close to Saint-Georges round out the program. François-Joseph Gossec’s support helped him enter the Parisian musical scene, and Saint-Georges performed and premiered his compositions in his mentor’s respected Concert des amateurs before assuming leadership. It’s unclear whether Saint-Georges studied with Jean-Marie Leclair. Still, he and every violinist in France certainly felt Leclair’s influence.

The Allegro ma poco from Leclair’s Violin Concerto in F, Op. 10, No. 4, enters on scalar patterns and dialoguing phrases that violinist Geneviève Gilardeau unpacks in finely shaped bursts. Gossec’s Symphony in D, Op. 5, No. 3 (“Pastorella”), incorporates a subtle palette of horns and flutes that shows off Tafelmusik’s ensemble balance and apt touch with the French style.

Even with contemporary audiences and present-day critics highlighting the imagination and richness of Saint-Georges’s music, he’s only recently begun to be performed and discussed on a more regular basis. Tafelmusik has once again shared Saint-Georges works that speak volumes even as they leave you wanting more. Daniel’s new foreword and Charlotte Nediger’s liner notes cover a lot of ground while also sparking curiosity to learn more about this fascinating individual.

ArkivMusic, which has a fairly comprehensive catalog of classical releases, lists nearly 100 recordings by Leclair, 47 from Gossec, and just 13 by Saint-Georges, whose oeuvre included orchestral works, chamber music, and vocal pieces, as well as operas and other works lost during the French Revolution. It will be interesting to keep comparing these numbers in the future.

Andrew J. Sammut has written about classical music and jazz for All About Jazz, The Boston Classical Review, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, Early Music America, The IAJRC Journal, and his blog. He also works as a freelance copy editor and writer. He lives in Cambridge, MA, with his wife and their dog.

Pingback: Classical Music In Color – The Second Street Dreams Audio Network