by Catherine Gordon

Published August 16, 2021

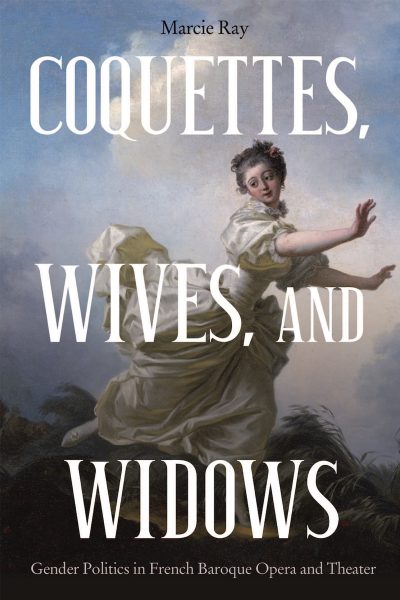

Coquettes, Wives, and Widows: Gender Politics in French Baroque Opera and Theater. Marcie Ray. University of Rochester Press, 2020. 191 pages.

In her book Coquettes, Wives, and Widows: Gender Politics in French Baroque Opera and Theater, Marcie Ray examines early 18th-century operas and theater works by composers and librettists who present common and conventional representations of women in their productions. When it comes to love and marriage, only four kinds are presented: coquettes, wives, widows, or those women who are indifferent. Ray’s descriptions of plots and exploits portray women as foolish, fickle, irrational, greedy, manipulative, and/or subservient in stage works that are entertaining and even comical.

Her analysis, however, presents a serious commentary on women’s status within the cultural and social hierarchy from 1701 to 1745, a period in the history of French stage works that has not received very much scholarly and artistic notice. Ray argues that any progress made by women during the middle of the 17th century through women-centered thought and in literary works regarding love and marriage was suppressed by the end of the century and replaced by the need to enforce values promoted by the male-dominated culture. This predilection is also reflected in the emergence of new family laws that consolidated male authority.

Her analysis, however, presents a serious commentary on women’s status within the cultural and social hierarchy from 1701 to 1745, a period in the history of French stage works that has not received very much scholarly and artistic notice. Ray argues that any progress made by women during the middle of the 17th century through women-centered thought and in literary works regarding love and marriage was suppressed by the end of the century and replaced by the need to enforce values promoted by the male-dominated culture. This predilection is also reflected in the emergence of new family laws that consolidated male authority.

Each chapter focuses on musical/theatrical works performed at each of the four major stages utilized in 18th-century Paris: the Opéra, the Comédie-Italienne, the Opéra-Comique, and the Comédie-Française. A particular genre of work and female characterizations, from the coquette to the prude, are then featured in each chapter. Various types of “dangerous” women are represented in the book through an analysis of one musical work in Chapters 1 and 4, and more than one in Chapters 2 and 3. Also explored are the greater social, cultural, and even legal issues pertinent to each production.

The coquette is featured in Jean-Philippe Rameau’s comic ballet Platée, ou Junon jalouse (Platée, or the Jealous Juno, 1745) in Chapter 1. Not only does the work characterize the flirtatious coquette who uses sex to trap her prey, but it also presents a scenario whereby a non-noble woman manipulates a nobleman into marrying her in a story about money, sex, and social mobility. Rameau’s work underscored the “dangers” of class instability and addressed the urgent need to maintain social order, which became all the more acute throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.

Chapters 2 explores the widow, “‘A Mistress of Her Own Affairs’: Inhibiting the Widow’s (Sexual) Independence.” In Les Amous déguisez (Cupids in Disguise, 1726) by Alain-René Lesage, Jacques-Philippe d’Orneval, and Louis Fuzelier, scenes representing various kinds of lovers are revealed according to a survey ordered by Venus. Scene 8 presents the widow Madame Doucet, who is running a “charity” in which she hires a gentleman to help run her estate in exchange for sexual favors. Ray analyzes other works from the Comédie-Française and the Comédie-Italienne as well, particularly Desportes’s Veuve coquette (The Coquettish Widow, 1721), which features a widow, far past her prime, who places her sexual needs above those of her daughter. These representations confirmed real concerns regarding the “over-sexed” widow who rejected marriage and exercised her independence since she was often financially secure and out from under the control of a man, be it a husband or father.

A woman seeking separation from her husband was seen as another type of women living a life of debauchery. She was viewed as dangerous because she defied the conventional family and therefore challenged social order. This type of woman was often the subject of works performed at the forains, or fairgrounds, which tended to be more sympathetic towards these outsiders. Works performed at the Comédie-Française and Comedie-Italienne, however, were more likely to present a conservative characterization: Married women who sought independence must be either punished or “run out of town.” A reaffirmation of male authority was also recommended as a way to uphold the hierarchy of power.

Finally, André Campra’s ballet “Aréthuse, ou la vengeance de l’Amour (Arethusa, or Cupid’s Vengeance, 1701) is analyzed in Chapter 4. In this work, based on a tale from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Arethusa, a chaste nymph, is pursued by Alpheus. Despite her defiant resolve against love, he finally wears her down and reduces her to a compliant mistress. The “indifferent woman” is a trope found in literary and musical works throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. Ray points out that women, such as Madeleine de Scudéry and Madame de Lafayette, offered through their literary works alternatives to marriage that permitted women to choose their own partners after a long courtship. These ideas were not met with enthusiasm by many men.

Marcie Ray ingeniously uses commentaries on social issues that affected women’s lives in the real world as an analytical tool to reveal many aspects — some nuanced, some openly explicit, some comical, some ironic, and some openly antagonistic — in the librettos and musical works that demonstrated a particular ideology: marriage is essential, and the only way to save a woman from her own foolishness, weakness, and immoral nature. The majority of these commentaries confirmed without reservation that married women should not be able to avert strict rules pertaining to class order, ideals of femininity, and sexuality.

In the Epilogue, Ray argues that “the truly durable lessons of this book are the ways Western culture has learned to frame women’s choices, perspectives, and experiences as excessive or motivated by immorality” and adds that “our contempt for disobedient women has endured.” Perhaps most importantly, Ray successfully demonstrates that entertainments, no matter how comically ridiculous, serious, or compelling, reflect, inform, and reveal broader political and social systems that affected the lives of real women in the real world for generations.

Catherine Gordon is a professor of music at Providence College, harpsichordist, and musicologist. Her first book, Music and the Language of Love: Seventeenth-Century French Airs, was published in 2011, and her second book, Catholicism as Musical Discourse: the Re-conversion of Women Through Seventeenth-Century Sacred Songs, is forthcoming from Oxford University Press.