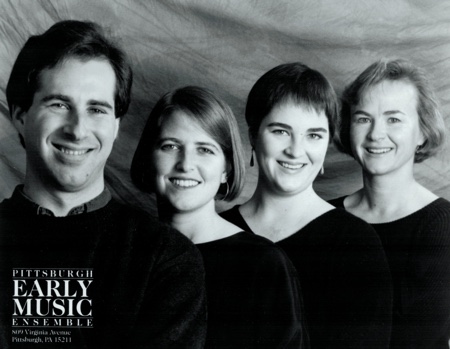

(Photo by Alan Adams)

By Mark Kanny

The merger of the two major players in Pittsburgh’s early music scene, announced after the conclusion of their seasons, emphasizes the strength of the younger organization, Chatham Baroque.

The action was precipitated by the December resignation of the executive director of Renaissance and Baroque, formerly the Renaissance and Baroque Society of Pittsburgh. Founded in 1969, R&B is a presenting organization that brings in touring ensembles from around the world. It turned to Chatham Baroque for administrative support promoting and managing its remaining concerts of the season.

Chatham Baroque has an unusual organizational structure, which includes salary and fully paid health benefits for its musicians and administrative staff. It had helped R&B administratively a few years earlier.

This spring, the boards of each organizations began to think about a merger. R&B knew its executive director position wasn’t a full-time and full-salary job. Chatham Baroque saw the two organizations’ complementary missions made for a great match. Both offer historically informed performances on period instruments. Their roles were once compared to a wine importer and a vintner.

Chatham Baroque is the larger organization, with an executive director and additional staffer, plus an intern. Its budget for the 2017-18 season was $415,000. It has more than $100,000 in cash reserves. R&B’s budget was $135,000. It has $30,000 in cash reserves. Some members of the R&B board will now join the board of Chatham Baroque. Both will announce their 2018-19 seasons in June.

Chatham Baroque was called the Pittsburgh Early Music Ensemble at its debut in May 1991. It was a quartet consisting of Jeffrey Stock (recorders), Emily Davidson (baroque violin), Patricia Halverson (viola da gamba), and Vivian Montgomery (harpsichord). Stock’s father was composer David Stock, founder of the Pittsburgh New Music Ensemble.

“I think we had no idea we would get traction,” Halverson recalls. “I had just moved to town. Jeff Stock and Emily Davidson had just returned to their home town. It was luck. After our first concert, we decided to have a series, but we had no idea of where it would go or how long it would last.”

The new group faced many challenges. Its players made just $400 the first year. It had trouble maintaining keyboard stability. Montgomery left after two seasons. After another year of trying out harpsichordists, Michelle Roy was hired, but she didn’t stay long, either.

The musicians looked up to Renaissance and Baroque. Its concert offerings were of the highest quality, featuring big names and emerging stars in the early music world. Although in one respect the Pittsburgh Early Music Ensemble was competing for the ticket and donation dollars of early music enthusiasts, it’s also true that R&B had ploughed the ground for the new group by having a well-developed and substantial audience base.

At the same time, the new group was laying the groundwork for its future strength. Davidson insisted the musicians receive a salary, even if small at first. She pushed for health benefits. She also knew the group needed to be a 501(c)(3) organization to be able to apply for grants.

“We were in the right place at the right time,” says Halverson. “The ’90s were a pretty healthy time in our country, and aside from Renaissance and Baroque, we didn’t have a lot of competition.”

When Stock and Roy decided to leave, the group made the right moves to become stronger and more stable. It raised the pay and added paid health benefits to attract strong players. The treble lineup was changed to two violins by hiring Julie Andrijeski in 1996, a brilliant musician who brought other strengths. It also hired Scott Pauley, who plays theorbo and other fretted instruments, for continuo. And thanks to a Chamber Music America grant encouraging residencies, it was able to affiliate with Chatham College, which became a university in 2007, and changed its name to Chatham Baroque.

The new players raised the group’s performance standards and sharpened it stylistic focus, enabling Chatham Baroque to begin an acclaimed series of recordings on the Dorian label.

“It was an extremely exciting time,” says Andrijeski. “It was my first real job outside of school, and I’d been in school a long time. I had the time and space available to help make the quartet special, to play with colors, shapes, and gestures, and really have a group that knows itself very well — a luxury, I think.”

Two of her enthusiasms helped define the group. She loves 17th-century repertoire and is a devotee of Baroque dance.

Her colleagues were excited about Baroque dance, “because it provides an extra visual element when we play,” Andrijeski says. “It also informs how we play the music. It gives a ‘dancier’ feel that’s so essential for most of the music that makes up baroque repertoire.”

Pauley was just out of school, too, and had started a freelance career in London when he saw his future ensemble’s advertisement for a harpsichordist. He knew Halverson “a bit” from each having studied at Stanford and called to see if the ensemble would consider theorbo for the continuo role.

Pauley notes that in reading Baroque music the figured bass line indicates the chords and inversions to be played.

“It’s the same principle on keyboard, or theorbo, or lute,” he says. He plays the bass line with the thumb of his right hand on the theorbo’s long strings, the chords with the fingers of his right hand on the set of shorter strings. “You learn over time to adapt and string it all together so it sounds fluid. I don’t have to change anything, unless it’s a written-out keyboard part, like an obbligato.” If the bass line has a lot of fast notes, Halverson will play them on gamba while Pauley emphasizes the harmonic rhythm.

He had a great time at the audition and saw the group had good board members, lots of energy, and a niche with room to grow.

“Pretty quickly, through the leadership of Emily and her mother, Leann Norman, they made our positions salaried and full-time,” says Pauley. “We were very small and probably a little naive, but we kept plugging away. We grew organizationally and artistically. We made CDs and toured the U.S. and South and Central America. A lot of my theorbo-playing colleagues have to make their living traveling to different cities each week. I feel lucky to have joined Chatham Baroque, to have a home base, fairly stable for raising a family and owning a home. These things are not a given in early music.”

The death of Davidson in November 2003, at 36, was a shock to the ensemble, especially since she’d been diagnosed with cancer only seven months earlier. The group decided to continue as a trio, its format to this day.

In 2007, Chatham Baroque faced another personnel change when Andrijeski decided to leave to teach at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. The winner of the auditions was Andrew Fouts, an exceptionally accurate violinist — a virtuoso with sensitivity and an engaging personality.

Chatham Baroque has continued to grow with Fouts as violinist. The group is usually supplemented by guest artists of the caliber that R&B brings to Pittsburgh for its concerts. Chatham Baroque’s collaborations with other Pittsburgh musical groups have deepened. It has provided the foundation for Pittsburgh Opera productions of six Baroque operas, by Monteverdi, Cavalli, and Handel. It performed Italian Baroque music at Heinz Hall before a 2012 performance of the Verdi Requiem with Manfred Honeck and the Pittsburgh Symphony. It also regularly teams up with the a capella choir The Pittsburgh Camerata and regularly performs at Calvary Episcopal Church.

Fouts says hiring its current executive director, Donna Goyak, a year and a half ago has revitalized the organization. A veteran of artistic non-profits, Goyak reassessed the organization to identify opportunities to be seized and upgrade the infrastructure, including the computer system. The group has greatly increased its internet presence and has had 190,000 views of its YouTube videos.

Chatham Baroque’s financial strength comes from a diverse revenue stream established during Davidson’s tenure and greatly expanded since then. In 2017-18, 28 percent of its revenue came from concerts — ticket sales and fees for touring, residencies and collaborations. Numerous grants from corporations, foundations, and government account for 52 percent of its budget. Individual giving, including from board members, accounts for 15 percent of its revenue.

Educational activities account for a significant part of the group’s schedule. The musicians teach at Carnegie Mellon University, which has an excellent baroque ensemble, and are active in early childhood education, which is well supported by grants.

The Peanut Butter and Jam Sessions are for pre-schoolers and their parents. The atmosphere could hardly be more informal and nurturing. Chatham Baroque musicians are frequently joined for these concerts by a guest artist who might be performing on one of the group’s main-series programs or someone playing musical saw with bow or mallet. Kindermusik teacher Lynda Wingerd leads the children in musical activities when they’re not listening to the pros.

Playing Peanut Butter and Jam Sessions has had the unexpected benefit of loosening the group up. Fouts says he had no experience being around children before he started playing these events but took to it quickly.

“Initially I was nervous, thinking what could I offer? But then I realized, you just be yourself and magnify yourself,” he says. “I almost become a caricature of myself. I like to ham it up in front of the kids, be a little silly, and come down from the stage and be with them.”

The result is that the group’s serious concerts also feel more inviting. Partly it’s the informal banter, when extra players come onstage or during tuning between pieces, a skill developed adapting to the unpredictability of children.

But it is the musicians’ unabated enthusiasm for the repertoire they perform that is most winning. Chatham Baroque concerts still have the irresistible feeling of discovery, which has been an enlivening element since the ensemble’s earliest days sharing riches from before 1750.

Mark Kanny was classical music critic of the Pittsburgh Tribune Review, 1999-2016, and previously wrote for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, New York Times, and other publications.