George Louis Houle (Nov. 21, 1927 – Jan. 7, 2017)

By Glenna Mount Houle

George Houle was born in Pasadena, CA, and spent his early life there. From the age of 13, he studied oboe with the principal oboist of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Henri de Busscher.

He first went to Stanford University in 1949, when he was hired to play oboe for a Music Department opera and then was offered a music scholarship in lieu of payment. He received bachelor’s, master’s, and Ph.D. degrees and studied with Putnam Aldrich and Leonard Ratner. He married Constance Crawford in 1952. They had four children and divorced in 1967.

After teaching general music courses at Mills College and the universities of Colorado and Minnesota, he returned to Stanford in 1962 and began to build a program in the performance of early music. He learned to play and teach baroque oboe, recorders, and other early wind instruments. Professor Houle believed that it was necessary to understand the rhythms of Renaissance and Baroque dances in order to play them well, so he and his students learned to dance. His strong belief in uniting the performance of music with its history and theory remained a cornerstone of his academic career. Under his direction, many students were awarded the Doctor of Musical Arts (DMA) degree in the performance practice of early music.

During 1972–74, he took leave from Stanford to direct the New York Pro Musica in concert and opera productions that toured in the U.S., Central and South America, and Europe. He returned to Stanford and taught there until his retirement in 1992.

He was the author of Meter in Music 1600–1800; Doulce Memoire, A Study in Performance Practice; Le Ballet des Facheux: Beauchamp’s Music for Molière’s Comedy; and was the editor, with Glenna Houle, of The Music for Viola Bastarda by Jason Paras and of many articles. His greatest enthusiasm was to use scholarship in the service of musical performance. He taught countless classes, directed many ensembles, and presented innumerable concerts throughout the years. He was oboe soloist with the Houle Consort.

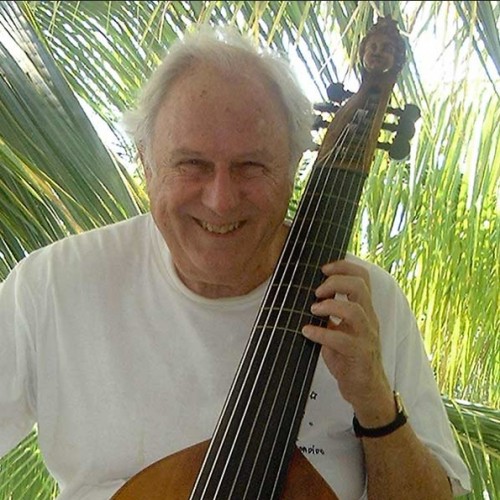

He enjoyed a happy and productive retirement, with more time to be with his family. He learned to play the viola da gamba and became the editor and publisher of the gamba sonatas of C. F. Abel and August Kühnel, as well as other music suitable for the gamba. He continued his teaching career for nineteen years, offering fall and spring classes at the University of San Francisco’s Fromm Institute. He and his wife, Glenna, enjoyed extended winter vacations in Oaxaca, Mexico.

In 1998, his friends and former students came from around the U.S. to celebrate his 70th birthday with concerts, musicological papers, and good fellowship. In 1999, he received from Early Music America the annual Howard Meyer Brown Award for “lifetime achievement in the field of early music.”

He is survived by his wife of 49 years, Glenna Mount Houle; son David (Jaye) of Tallahassee, FL; daughter Ann of Monterey; son Alan Holiday of Santa Cruz; daughter Melissa of Sunnyvale; grandson Nathan Holiday; former wife Constance Crawford of Palo Alto; sister Jeanne Johnson and nieces Amy of Escondido and Sarah McElaney (Dave) of Palo Alto.

He will be remembered for enriching the San Francisco Bay Area’s musical life with frequent concerts of Baroque and Renaissance music. He was greatly appreciated by his talented and dedicated former students who are playing, teaching, thinking about, and writing about music all over the world.

A memorial is planned for the spring. Gifts designated for the George Houle Memorial Early Music Scholarship Fund should be noted as such, made payable to Stanford University, and sent to:

Friends of Music

Braun Music Center

Stanford University

541 Lasuen Mall

Stanford, CA 94305

TRIBUTES

Stanford degrees are listed, to indicate when each person studied or worked with George Houle.

Dr. Jack Ashworth, MA 1974, DMA 1977

Professor of Music, Emeritus, University of Louisville School of Music

Louisville, Kentucky

George was an inspiration. For me, the impatient scholar who just wanted to be playing all the time, he was an ideal mentor. His championing the Stanford tradition of scholarship with performance prepared me to do the work I’ve been doing for the past 40 years. I’ve included a session of Renaissance dance in virtually every class I’ve taught. I was told, before I’d even met George, that he could listen to a consort of six instruments and fix whatever was wrong with two or three comments. I’ve used this as a model in my own coaching.

After I began serving on workshop faculties, it was an added pleasure to reconnect with George and Glenna as students at Port Townsend, Pacific Northwest Viols and the Conclave. I don’t mind saying it was intimidating at first to be on the other side of the music stand, but that lasted for about the first ten minutes of our first workshop together. We were all there in pursuit of a common goal: to make beautiful music together. Come to think of it, that was my experience while a graduate student as well.

John Dornenburg

Lecturer in Viola da Gamba, Stanford University

Lecturer in Violone, University of California, Berkeley

Professor of Music, Emeritus, California State University at Sacramento

Oakland, California

I knew George as a friend and musicologist, but I also knew him as a student on the viol and as a member of our Monday evening consort sessions back in the 1990s. He played such a large role in the direction our lives took after we moved to California—my position at Stanford, the Stanford Baroque Orchestra, his many program notes for our CDs and concerts, his editions of Kühnel and Abel, his encouragement of many projects, and his thoughtful attendance at so many performances—we will miss him dearly.

Dr. Ross Duffin, DMA 1977

Professor of Music, Head of Historical Performance Program, Case Western Reserve University

Cleveland, Ohio

I first encountered George Houle as an undergraduate in London, Ontario, when he came to lecture on some aspect of Baroque music. I remember being stunned that he was talking about music and demonstrating Baroque dance steps to illustrate his points. When he was on tour with the New York Pro Musica, I went with recent Stanford D.M.A. Tim Aarset to meet him and see the production. At that point, I knew I would be applying to Stanford. When George returned, I took Baroque performance practice from him and was coached on chamber music. This was George in his element—caring deeply about musical gesture, about French Baroque music, and about historical performance generally. His brilliance, his energy, and his commitment were all models for me as I tried, over the years, to recreate elements of the Stanford program at Case Western Reserve. CWRU’s HPP program owes a lot to George’s vision of performance practice and historical dance as essential elements in the performance of early music.

Mary Elliott, MA 1980

Active Violist da Gamba, San Francisco Bay Area

El Cerrito, California

George was my teacher, mentor, and, in later years, dear friend. His creation of a class, with just the two of us, to debate the meanings of the performance practice markings in the Sibley Library’s Book II of Marais’ Pièces de viole, was one of the highlights of my years at Stanford. The wealth of scholarship and discernment he shared with me was a treasure. His classes were riveting, his coaching inspired, and through it all shone his passion for music. After his retirement, I had the pleasure of playing viol consort music with him, witnessing his teaching enchant new audiences at Fromm Institute classes, cycling with him, and enjoying his amazing soups. His joy in all aspects of his life was boundless.

Dr. Adam Gilbert

Acting Assistant Professor of Music, Stanford University 2003-05

Associate Professor and Director, Early Music Program, University of Southern California

Pasadena, California

I will be looking up in the sky tonight. I know that George passed a lot of his “fire in the belly” onto his students, but I am certain that he rose up with enough left for a good sized star or two.

Dr. Patricia Halverson, MA 1983, DMA 1988

Professional Violist da Gamba with Chatham Baroque

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

George’s impact was tremendous for so many. Just a few of his gifts were his scholarship, teaching, his performances, his editions, and his tireless pursuit of new knowledge.

Dr. Elizabeth Hays, MA 1966, PhD 1977

Associate Professor of Music, Emerita, Grinnell College

Grinnell, Iowa

I keep thinking back to those wonderful days with George and have been struck by how much he looked out for us, in addition to bringing us so much—laced with wise insights. His thoughtful assessments of various subjects were crucial to our lives and careers. He was a true pioneer, not just in wisely establishing the DMA degree (which also had a good effect on the PhD) but in forging new territory with his own studies as well. And he was such a fine teacher—a kind and genial but decisive force for bringing each of us along in accordance with our capacities.

Carol Herman

Professional Violist da Gamba, Composer, Poet, Teacher, Actor

Claremont, California

What a legacy he left: an intelligence and wisdom that guided and touched so many. The early music world was blessed by his presence. George was a giant among us.

Joyce Johnson Hamilton, Doctoral Studies 1969-74

SFEMS Board Vice President and Concert Committee Chair

Professional Trumpet, Early Trumpet, and Cornetto Player

Orchestral Conductor

My enthusiasm for early music and performing on period instruments led to my enrolling in Stanford’s program. Life as a graduate student in music at Stanford seemed idyllic. But it was on Friday afternoons when the performance practice students all gathered on the verdant lawn behind the Knoll that this sense of living an abundantly rich life was heightened. For that hour, it was all about the dance!

With an amazing grace and skill, George demonstrated bourrées, gavottes, sarabandes, pavanes, galliards—all of the dance forms found in the music of the composers we were studying. We students all struggled with our feelings of awkwardness but began to bound around quite proficiently by the end of the course. The Friday dance classes on the lawn with the gardens and gorgeous view of golden, rolling hills in the distance was the one common experience that all of the performance practice students shared and carried with them as a kinesthetic awareness of the stresses, accents, points of repose and lift that could be expressed in performing early music. Those classes offered invaluable lessons and created life-long happy memories of George in his element.

Dr. William Mahrt, PhD 1969

Associate Professor of Early Music and Musicology, Stanford University

Director, Stanford Early Music Singers

Director, St. Ann Choir, Palo Alto, California

Being a brilliant performer, an excellent theoretician, and an accomplished scholar, George Houle’s ebullient enthusiasm made him an extraordinary and inspiring teacher. His intense conviction concerning the intimate relation of performance and scholarship was the fulcrum of all he did as a teacher. His playing of the modern oboe was sensitive and distinctive, so much so that when I heard the oboe played from a distance, it was unmistakable that it was he who was playing; I will never forget his virtuoso playing of diminutions on the recorder. He was one of the most important influences in my decision to change my focus to early music. I had been a player of modern wind instruments, and he handed me a recorder and confidently said, “Play this”; that experience was a beginning of all I did since. I treasure our collaboration in the early music program and the confidence and encouragement he gave me as a colleague.

Anthony Martin, BA 1968

Lecturer, Baroque Violin, Stanford University

Stanford Baroque Soloists

Professional Violinist/Violist

Richmond, California

Not only will I remember the good times we had, but also the seminal influence he had on my life and my career.

Dr. Jameson Marvin, MA 1965

Director of Choral Activities and Senior Lecturer, Emeritus, Harvard University

Director, Jameson Singers

Lexington, Massachusetts

George Houle was the best and most important teacher I have ever had. My love and profound interest and enthusiasm for performing Renaissance choral music had its foundation in those many classes taught by George.

Sarah Mead, MA 1977

Professor of the Practice of Music, Brandeis University

Professional Violist da Gamba and Instructor of Viola da Gamba

Natick, Massachusetts

George was my true mentor. It was through my work with him that I learned what that term means. His honest passion for the music he loved shone through his work, illuminated by the clarity of thought he brought to understanding it. I was so grateful to be able to rehearse and perform with him as a continuo player during my time at Stanford, in addition to learning from him in the classroom and as he oversaw my research.

Dr. Leta Miller, BA 1969, PhD 1978

Professor of Music, Emerita, University of California at Santa Cruz

Santa Cruz, California

Last year, I received a distinguished teaching award from the Arts Division. On the way out of the ceremony, someone stopped me and asked if I knew George. I replied that, indeed, he was the inspiration that led me to musicology and was the guide for my teaching during my career.

Rosamund Morley

Professional Violist da Gamba

Parthenia Consort of Viols

New York, New York

From the first time I met him, which must have been 20 years ago, he was always so generous with his ideas and his time, and he never let a non-musicological musician of early music feel any less important for their less comprehensive knowledge of the repertory. He was warm and accepting of all of us.

Dr. Herbert Myers, BA 1964, MA 1966, DMA 1981

Lecturer, Renaissance Winds, Stanford University

Director, The Whole Noyse

Menlo Park, California

George was such an integral part of so many aspects of my life, and I owe him so much. I can hardly express my gratitude.

Dr. John Robison, MA 1972, DMA 1975

Professor of Musicology, Collegium Musicum Director, University of South Florida

Tampa, Florida

Those of us who knew him as a teacher, and later on as a friend in life, will be eternally grateful that we could have him on earth for such a long time, because he truly made the world a better place for all.

Marion Rubinstein, BA 1973, With Honors

Co-Director, The Albany Consort

Sunnyvale, California

George has very much influenced my life’s course. He was always so kind and supportive, and has helped me realize the importance of both scholarship and performance in a balanced way. This is very rare for most musicians.

Dr. Sally Sanford, MA 1976, DMA 1979

Concert Singer in Recital, Opera, Oratorio; Voice Teacher; Choral Clinician

Ensemble Chanterelle

Concord, Massachusetts

Recently, I was involved in a DMA dissertation proposal defense committee. The student’s advisor suggested that he study meter and directed him to George’s book [Meter in Music 1600–1800]. I naturally seconded that suggestion and explained my deep connection to George and how much I had learned from him and how terrific the book was. We will never be able to measure the full extent of George’s legacy—he had such a deep influence on so many of us who were his students—because we will never be able to gauge the impact he is having on his students’ students, as well as on those who are just lucky enough to encounter his work.

Dr. Beverly Simmons, BA 1971, MA 1973, DMA 1976

Executive Director of Quire Cleveland

Cleveland, OH

George Houle literally changed my life. I went to Stanford-in-Austria as a math major and, thanks to his courses, returned as an early music devotee. His professional renown gave us access to historical instruments in the major European museums—and I was hooked! Having taught me Music Appreciation, he eventually advised me through my master’s and doctorate in early music performance. Through the Stanford program, I met my husband, Ross Duffin, further proof of George’s influence. Inspired by his merging of performance and scholarship, I have endeavored to apply that approach to my own conducting and performing. Over nearly fifty years, George became a dear friend—he will always be close to my heart.

Martin Stoner, BA 1971

Concert Violinist

New York, New York

George was such a special and irreplaceable person. I shall never forget George’s kindness to me over so many years as he unselfishly gave of his time and knowledge to help point me in the right direction and give me his expert opinions and guidance.

Dr. Jane Sugarman, BA 1972

Professor of Music and Director, Ethnomusicology Program at The Graduate Center, CUNY

New York, New York

As an undergrad, he permitted me to take four graduate seminars in early music, which was a great honor and certainly the most stimulating experience I had in my college years. I think particularly often of his organology course, which far surpassed the two (!) I took as a graduate ethnomusicology student. One day I arrived to find that we were all going to sit on the floor and listen to a recording of Tibetan Buddhist chant—there was always a hint of ethnomusicology lurking around the early music program. But George also thought in an ethnomusicological (or anthropological) way about instruments and how they fit into society, thus preparing me well for my graduate studies.

Marc Tessier-Lavigne

President, Stanford University

George was highly regarded as a scholar, teacher, and mentor at Stanford and throughout the community. He will be deeply missed.

Lynne Toribara, MA 1973

Head of Monographic Processing (ret.) at Santa Clara University

Portola Valley, California

We have lost an inspiring teacher and a peerless advocate of early music. George has educated a generation of researchers and musicians who are keeping alive his legacy of impressive scholarship and fine performances.

Dr. Anne Witherell, MA 1973, PhD 1981

Instructor, Low Winds, Lawrence University Academy of Music

Neenah, Wisconsin

Had it not been for his enthusiasm for dance history, I should never have studied at Stanford. What a beautiful place, and a happy time for me.

Benjamin Dunham, former editor, Early Music America magazine

I met George while we were both attending a conference at Yale on the training of young musicians. I was representing the American Symphony Orchestra League, but secretly my real aim as an early-music tyro was introducing myself to George, then the director of the New York Pro Musica.

Seated at dinner, it was George who sought me out, much to my surprise. He asked if I knew Richard Lert, the elderly leader of the Symphony League’s conducting workshops. I did; it was one of my gofer jobs to pick Lert up at Dulles Airport and drive him to Orkney Springs, Virginia, where the workshops were held. Lert was then in his early 90s and revered as a living throwback to the Golden Age of Conducting. As a boy, Lert had met Johannes Brahms (his father was a member of the Vienna Singverein), and as young conductor Lert was privileged to carry the “sticks” of the great conductor Arthur Nikisch.

“How do you know of Richard Lert,” I asked, unable to make the connection in my mind.

“He taught me everything I know about music,” George said. He stopped there — I can still remember the hint of a smile and the twinkle in his eye — waiting for the shock to leave my face.

It turned out that as a teenager, George had played oboe in the Pasadena Symphony, the little community orchestra that Lert led after accompanying his wife, Vicki Baum, to Hollywood, where she wrote the screenplay for her novel Grand Hotel (Baum had been his harpist in Darmstadt). Lert’s baton could find the sound in an orchestra like a divining rod, but he never got the hang of conducting major American orchestras “on the clock.” He loved sharing his musical instincts and knowledge, however, with the many young players in his orchestra, and one of them became the eternally curious and imaginative paragon of our early-music world, George Houle.