by Natasha Roule

Published September 27, 2021

“This was a woman aged at least 55 years who had once been blond, but today she had very beautifully streaked gray hair…but because she had become too powerful, they put her in the chorus.”

So wrote the police inspector Jean-Baptiste Meusnier about French opera singer Madeleine Tulou around the year 1753. Meusnier penned these words in a massive report, Discipline des mœurs, bulletins de police sur la vie privée des actrices, danseuses et cantatrices de Paris, that he was compiling on the moral state of Paris, the city where he lived and worked. As the title of his report makes clear, much of Meusnier’s work entailed conducting investigations of the lives of professional performers, whom contemporaries too often viewed as morally promiscuous by virtue of their chosen careers. Whatever the actual nature of her character, Tulou numbered among Inspector Meusnier’s subjects.

Tulou is a fascinating character in music history, although we know little about her. Beyond Meusnier’s report, her name surfaces in a handful of opera libretti from 18th-century France, allowing us to track her career from minor soloist at the Paris Opéra to prima donna of the city of Lyon before she fell into obscurity in the ranks of the Paris Opéra chorus — a fate to which she was relegated because, according to Meusnier’s report, she “had become too powerful.” Yet this apparently power-hungry soprano is all but forgotten today. She is not alone: How many women opera singers from Tulou’s lifetime are mentioned in concert programs or recording booklets? The answer remains very few.

In our performances of French Baroque opera, we tend to associate the genre almost exclusively with the male composers who marked salient points in the development of early French operatic style, such as Jean-Baptiste Lully, who invented French Baroque opera under Louis XIV, or Jean-Philippe Rameau, who rejuvenated the genre some 50 years after Lully’s death. If the focus of a performance or recording of French Baroque opera is not on a composer, it tends to be on one of the genre’s male patrons, such as Louis XIV himself, or on one of the luxurious chateaux where the genre was first performed, such as the palace of Versailles. The association of French Baroque opera with Lully, Rameau, the Sun King, and the French royal court is not misplaced. Without these individuals and placemarks, French Baroque opera would never have come into being.

Yet as early-music practitioners and educators consider ways to diversify early music experiences for ourselves, our audiences, and our students, we need to invest in new approaches to French Baroque opera — approaches that enable us to expand our exploration of the repertoire to include the myriad individuals who contributed to the genre, such as Tulou. In an effort to give Tulou a place in the historical narrative of French Baroque opera, here’s a brief summary of her life, which constitutes almost everything we know to date about this long-forgotten singer, as well as a few suggestions for how Tulou can teach us to expand our approach to French Baroque opera performance.

Tulou’s Story

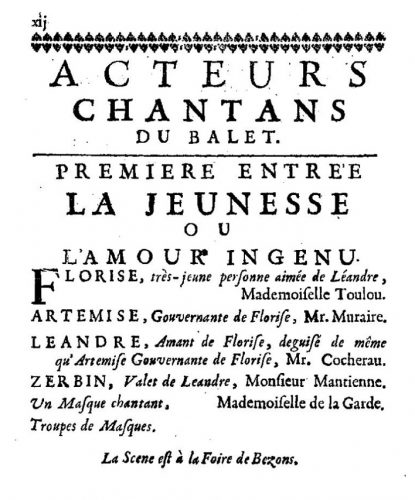

Tulou was born around the year 1698 to a butcher in Lyon, France. About age 20, she traveled to Paris, where she was hired at the Paris Opéra to sing minor solo roles, such as nymphs, shepherdesses, and goddesses, starting with her debut as the young lover Florise in a revival of André Campra’s ballet Les Ages in 1718.

The operas in which Tulou performed are vastly underrepresented in modern discography. Ranging from Jean-Baptiste Stuck’s Polydore to André Cardinal Destouches’s Amadis de Grèce, these works represent the stylistic hodgepodge of the Parisian musical scene in the first quarter of the 18th century, when audiences clamored for new Italian musical idioms even as they raved over the older French operatic style pioneered by composers, such as Lully, at the end of the previous century. It is hard not to imagine how thrilling a time it must have been for Tulou, a young singer in one of Europe’s most prestigious opera houses.

Yet within six years of her Parisian debut, Tulou returned to Lyon. The reason remains a mystery, but her migration from the French capital to her native city proved a career game changer. Tulou’s name soon appeared in concert programs and opera libretti from Lyon’s two largest musical organizations, the professional opera company known as the Académie de Musique of Lyon and the Académie des Beaux-Arts, an amateur music society that hired professional musicians for solo and instrumental roles. The 1730s saw Tulou starring in multiple title roles of well-known and popular operas, including Lully’s Armide, which audiences from Tulou’s time to the present day have frequently considered to be the composer’s masterpiece. Beyond these high-profile gigs, Tulou was hired to sing in concerts at the home of Louis Nicolas de Neufville, the governor of Lyon and one of the most important aristocrats in France. According to Meusnier, Tulou became nothing less than “la vogue de Lyon” during her time in the city.

An 18th-century portrayal of Armide, whose role Madeleine Tulou sang in a production of Lully’s Armide at the Académie des Beaux-Arts of Lyon. François Joullain, Rinaldo Abandoning Armida, 1720-1762. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

By 1741, Tulou renounced her position in Lyon to move back to Paris. She returned to the French capital with her lover, a man we only know by his surname, Person. Although Tulou rejoined the roster of the Paris Opéra upon her return, Meusnier cautions us that “because she had become too powerful,” she was “put in the chorus.” Exactly what happened to put Tulou in this position remains unclear, but it may have been related to her professional success in Lyon, which could have caused her colleagues at the Paris Opéra to feel professionally threatened, or at least rankled, by Tulou’s stardom in her home city, which had long rivaled Paris as a focal point of artistic production and innovation.

Despite the gaps in her biography, Tulou has left us with more information than most female musicians active in French cities during the first half of the 18th century. Too often, we have little more than the names of women who danced or sang professionally in these cities, such as the Lyonnais opera singer Mademoiselle Moussa, whose last name suggests North African origins, or the Lyonnais dancer Mademoiselle Lefebvre, who joined her brother, also a dancer, in multiple opera productions in the 1740s. With time and effort, I am confident that many of these women’s lives will be illuminated, allowing us to better understand their contributions to this still relatively little explored period of musical history.

Even more well-known women musicians from the 18th century, such as the multi-talented opera singer Marie Justine Benoîte Duronceray (1727-1772), wife of Charles Simon Favart, still claim little space in historical narratives of the period. Portrait of a Woman, Said to be Madame Charles Simon Favart. François Hubert Drouais, 1757. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Tulou’s Lessons

What can we learn from Tulou, a singer who, over the course of her career, achieved celebrity status in one of the largest cities in France and was anywhere from feared, reviled, disliked, or adored by audiences and fellow musicians in Paris who thought her too powerful for her own good? The fundamental lesson is that French Baroque opera is so much more than the story of Lully and Rameau schmoozing around Versailles. Here are a few thoughts as to how we can convey this to our students, fellow performers, and audiences:

- Reframe our concert narratives. Perhaps you are a chamber ensemble interested in exploring selections from one or more French Baroque operas. What if your performance programmed the repertoire to highlight the women artists who originated or revived specific roles in these operas? For each piece that you program, track down its first performer — these individuals are often listed on a piece’s Wikipedia page or in Grove Music — and include her name in the concert program. Or perhaps you might program multiple pieces that were all originated by the same performer, such as excerpts from Lully’s operas that his star soprano Marie Le Rochois first introduced to audiences in the 1680s.

- Encourage empathy. Empathy might seem a hard sell for a musical genre that we often stage with all the glitz and glamor of Versailles that our concert budgets can muster. Yet by shifting the focus of French Baroque opera from the royalty who sponsored it to the everyday men and women who sang it, we can help our audiences relate to the repertoire. Perhaps you are a music festival director planning to program a French Baroque opera as the centerpiece for your next season. Consider a pre-concert talk that focuses on the women performers who made opera possible at its first premiere. Having such a conversation may help audience members, especially those unfamiliar with or intimidated by the very elitist court of Louis XIV, discover and nurture empathy for the repertoire and the women who helped to create it.

- Be persistent and accept risk. The last several years have seen some truly spectacular productions of French Baroque opera, from the Boston Early Music Festival’s revival of André Campra’s Le carnaval de Venise (2017) to Opera Atelier’s Armide (2015). Despite the success of French Baroque opera revivals, the genre can be harder to sell than standard favorites, especially if the focus of a concert falls on a “niche” topic like the role of women in music. In other words, it is almost inevitably more of a financial risk to propose a work like Jean-Baptiste Stuck’s Polydore when Mozart’s Don Giovanni is guaranteed to draw in audiences who recognize the composer. Indeed, as the music industry stumbles forward after the painful hiatus imposed by the coronavirus pandemic, this risk may seem all the less attractive. But it is worth the effort and possible short-term cost to give voice to women like Tulou, who have remained predominantly silent amid our standard concert narratives of French Baroque opera. It is worth it — because it will ultimately make the music richer, more accessible, more meaningful, and, I have no doubt, more lovely to performers and listeners alike.

Natasha Roule holds a Ph.D. in historical musicology from Harvard University. She writes on the interplay of politics and opera in the 17th and 18th centuries, particularly the tragédies en musique of Jean-Baptiste Lully, and has taught at Aquilon Music Festival and George Mason University. She is preparing a critical edition of Marc Antoine Legrand’s La chûte de Phaëton (1694).