by

Published January 20, 2017

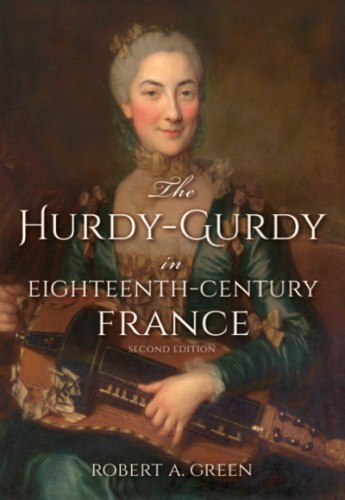

The Hurdy-Gurdy in Eighteenth-Century France, Second Edition. Robert A. Green. 117 pages. Indiana University Press, 2016.

By Valerie Walden

BOOK REVIEW — When most people hear the term hurdy-gurdy, they usually smile, raise an eyebrow, and ask, “A what?” Yet as Robert A. Green tells us at the beginning of this very interesting book, “the hurdy-gurdy,” unlike almost all other instruments known today, “has been in continuous use in Western Europe for a thousand years.” In this, the second edition of Green’s book (the first was published in 1995), the author has set out to share “new insights” and information about the hurdy-gurdy and its music to bring what has been considered an obscure instrument into the realm of practical historical performance, as well as to underscore its value in the contemporary world of folk music and jazz.

Green’s primary focus is on the hurdy-gurdy in Enlightenment France, where it was known as the vielle. The first of the book’s five chapters is devoted to the historical background of the instrument, beginning with the 17th century and continuing to the present day, providing details about the cultural environment that informed its use in each century. In chapter two, Green moves on to an in-depth examination of the compositions and stylistic features of French vielle music, his discussion fleshing out the musical language of each of the major composers for the hurdy-gurdy, including those musicians so obscure, such as Michon or Ravet, that their first names remain unknown. Since much of the music for vielle was also playable on the musette (a small bagpipe), Green helpfully includes comparisons of how the note range differed between the two drone instruments and explains the common harmonic plans of the music written for them. The chapter concludes with an examination of the method books published for the vielle.

Green’s primary focus is on the hurdy-gurdy in Enlightenment France, where it was known as the vielle. The first of the book’s five chapters is devoted to the historical background of the instrument, beginning with the 17th century and continuing to the present day, providing details about the cultural environment that informed its use in each century. In chapter two, Green moves on to an in-depth examination of the compositions and stylistic features of French vielle music, his discussion fleshing out the musical language of each of the major composers for the hurdy-gurdy, including those musicians so obscure, such as Michon or Ravet, that their first names remain unknown. Since much of the music for vielle was also playable on the musette (a small bagpipe), Green helpfully includes comparisons of how the note range differed between the two drone instruments and explains the common harmonic plans of the music written for them. The chapter concludes with an examination of the method books published for the vielle.

Chapter three examines the differences between performance instructions found in 18th-century methods and the practices of today’s hurdy-gurdy players who, as described by Green, “have studied the instrument as part of a living tradition.” Here we also find information for anyone wishing to understand the mechanical workings of this complex instrument and facts about continuo playing, rhythmic inequality, ornamentation, and double-stopping as applied to the 18th-century hurdy-gurdy.

Chapter four offers a comprehensive listing of 18th-century music for the vielle and where to find it in libraries, facsimiles, and modern editions. In the final chapter, Green returns to the various cultural contexts in which the hurdy-gurdy flourished by citing references to it in 17th- and 18th-century French literature. Placed as bookends, chapters one and five work together to demonstrate the rise and fall of the vielle’s popularity as it progressed from its original connection with blind beggars and other vagrants to the elite salons of the French aristocracy and then to an instrument popular in rural folk music.

The study concludes with an appendix of translated avertissements from the works of Jean-Baptiste Dupuits and a bibliography with a valuable list of primary and secondary sources. The author has also generously provided in the footnotes the original language for all French translations.

The book contains repetitions of factual information, wording, and proofreading. For example, the comment that blindness was regarded as a physical manifestation of moral blindness appears on both page xvii and page 2; the reader also needed clarification as to whether this association began in the 15th or 17th century. Words, particular with regard to adjectival constructions, could also have been more carefully chosen, such as the following phrases that appear in close proximity: “grating” A-flats on page 27 and “grinding A-flats” on page 29. As for proofreading, the name of the French composer Corrette is misspelled in the caption for the illustration on page 55 as “Corette.”

Despite these oversights, Green’s explanations and documentation are well researched and easy to follow, making this is a valuable book about a little-known instrument.

Valerie Walden received her Ph.D. from the University of Auckland. She is the author of One Hundred Years of Violoncello; A History of Technique and Performance Practice, 1740-1840, a chapter in The Cambridge Companion to the Cello, articles for the Reader’s Guide to Music, and 31 entries in the 2000 edition of the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. She is a faculty member at the College of the Sequoias in California, principal cellist of the Tulare County Symphony, and a member of the piano trio Trinitas.