by

Published March 28, 2016

Contributed by Benjamin K. Roe

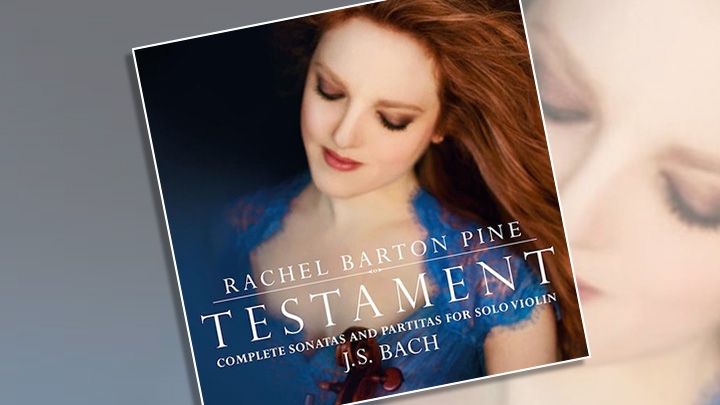

This month violinist Rachel Barton Pine is busy touring and promoting her brand-new recording of J.S. Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin, including an Easter Sunday performance of all six of the solo-violin masterworks at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. In Bach’s own autograph, he designates the Sonatas and Partitas as “Part 1,” with Part 2 being the far-more-commonly played Six Suites for unaccompanied cello. (You can check out our previous posting about the Bach Cello Suites here.) As Pine puts it,

The Sonatas and Partitas are among the greatest human achievements, and I have always viewed them with the deepest reverence. However, remembering Bach’s essential humility prevents these masterpieces from becoming overwhelming in their significance. Instead, each time I play them, I feel as though I’m conversing with the very best of friends….The internal symmetry of the six violin works points to the composer’s conception of them as a cycle, rather than a mere collection.

The Chicago-based violinist has also posted a number of her solo Bach performances on her YouTube channel this Early Music Month, including this performance of the Allegro from the Sonata No. 2 in A minor:

While the three solo Sonatas are in standard slow (Adagio or Grave) – fast (Allegro) – slow (Siciliana, Largo, Andante) – fast (Presto, Allegro) form, the accompanying Partitas mirror the suite of dance forms that Bach mined so effectively in the Solo Suites for cello. Such as the delightful Gigue that concludes the popular Partita No. 3 in E major:

But here’s where the “Testament” in our title comes in: This bouncy movement stands in stark contrast to the concluding movement of the preceding Partita – the emotionally searing, solitary journey of the epic Chaconne of the Partita No. 2 in D minor – a 14-minute movement that stands as one of Bach’s greatest and perhaps most personal of all his instrumental works.

As meticulous as he was in keeping track of his compositions, Bach wasn’t one to leave behind diary entries detailing his inner emotional world. But we do know that right around the time he composed this Chaconne he was confronting unimaginable grief: Bach had left town for a business trip, only to return home and find that his wife of twelve and a half years, Maria Barbara Bach, had died a week before and was already buried.

This was a woman who had already given birth to seven children and supported the young composer and organist in the early stages of what was already destined to be a significant career.

A few years ago, a German musicologist came up with the theory that the Chaconne was Bach’s way of processing the sudden, catastrophic change in his life: by embedding sturdy Lutheran chorales – what you might call the core DNA of Bach’s music – into the harmonic underpinnings of the near-16-minute solo movement. Such as the BWV 389 Chorale, Nun lob, mein’ Seel’, den Herren (“ Now praise, my soul, the Lord all that is in me praise his name!”), These short, simple works play a central role in Bach’s sacred music. And they carry with them a rich symbolism and lineage stretching back as much as two centuries before Bach harmonized them.

The result of this musical sleuthing was a remarkable recording released by violinist Christoph Poppen and the Hilliard Ensemble called Morimur, which combined the magnificent Chaconne with the imagined Bach chorales superimposed:

For her part, Rachel Barton Pine does not subscribe to this theory, calling it “convincingly debunked,”

“But we still continue to hope that perhaps it has some hidden, poignant extramusical meaning such as the crucifixion. Yet, the music need not justify itself beyond its notes and the emotions they portray. These thirty-four imaginative variations in three sections are grand, playful, peaceful, uncertain, triumphant, and tragic. Yet, somehow, Bach never loses the spirit of the dance.