by Jarrett Hoffman

Published December 9, 2019

It’s 1960, and a girl sits at home mesmerized, listening to a lively debate between two talking instruments.

Psychedelics? No, what’s playing is a children’s record, Said the Piano to the Harpsichord. The girl who can’t get enough of it is Elaine Funaro, who will go on not only to play the harpsichord, but also to take on the mission to prove that it is no mere fossil.

“I think my whole career has been about showing the harpsichord has a future. It’s not just the past,” Funaro said in a phone call from Durham, NC.

Funaro has fostered a new repertoire as artistic director of the Aliénor International Harpsichord Composition Competition. She’s also commissioned a contemporary instrument, built by Richard Kingston, and has recorded a bounty of new music.

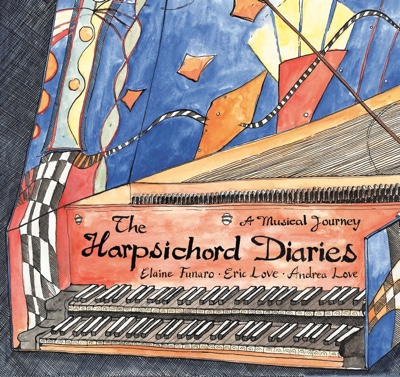

Most recently, she’s collaborated with two of her kids, twins Eric and Andrea Love, on a children’s book that ups the ante on bringing instruments to life.

It wasn’t easy. The Harpsichord Diaries: A Musical Journey was published this year after a long process that was both inspiring and vexing. Its journey has even included different media: Before it was a book, it was an audio play. And before it was an audio play, it was a one-woman show called A Nod to the 90’s.

That program, which Funaro first performed in 2004, combined stories from history with harpsichord music from the 1590s, 1690s, 1790s, 1890s, and 1990s. It was inspired by her discovery of Francis Thomé’s 1892 Rigadon, a true rarity — a harpsichord piece written in the 19th century, when the instrument had been all but left for dead.

Funaro hired Eric to direct a more theatrical remount of the show in 2008, and that sparked an even bigger idea. What if a character could experience first-hand the history and the evolving repertoire of the harpsichord?

The audio play Elena’s Dream was born. It begins with the young title character (a nod to Funaro herself) playing Bach on her grandmother’s harpsichord — and hating it. She throws a tantrum, runs up to the attic, kicks a ball into a pile of junk, and stumbles upon a leather-bound book, The Harpsichord Diaries.

“The harpsichord is stupid,” Elena says. And seemingly in response, the book opens up, booming out the Toccata from Edwin McLean’s First Sonata, a winner of the Aliénor Competition.

“I remember very distinctly when my mom first started playing that sonata. It’s just so good,” Eric said in a phone call from White River Junction, VT, where he is assistant artistic director and director of education for Northern Stage. “I knew that we needed contemporary harpsichord music to coax Elena towards the book and to create the magic.”

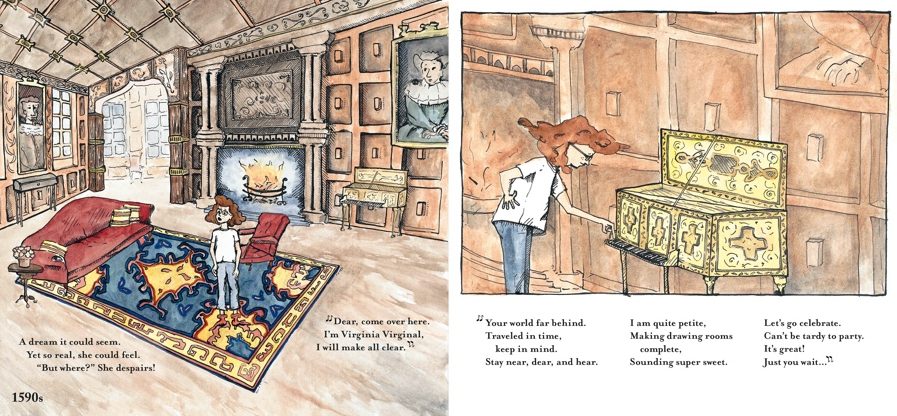

Our character is promptly transported back in time, where she befriends talking instruments from different centuries, with wildly different sounds and personalities. Eric, who wrote the play and narrates it, compared the story to Alice in Wonderland and The Wizard of Oz. “A young girl goes to a faraway land, meets crazy characters, and eventually comes back home changed for the better,” he said.

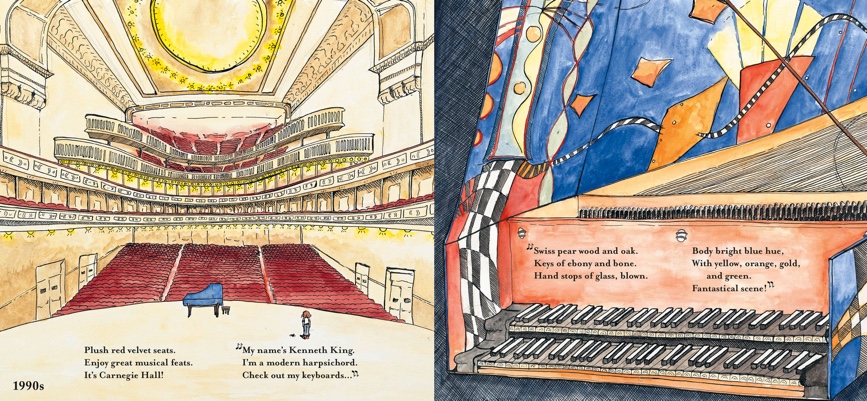

Those crazy characters include the informative Virginia Virginal (who brings Elena to a royal ball at Windsor Castle), the flirtatious Henrick Hammer (Henry Purcell’s personal instrument), the swashbuckling Thomas Taskin (who helps Hélène de Montgeroult save her own life during the French Revolution), the initially arrogant grand piano Érard (featuring Funaro’s husband, Randall Love, at the piano), and the wise Kenneth King (a large, beautifully designed modern harpsichord in Carnegie Hall).

Eric voices all 28 characters — instruments, humans, and even the dog Giles. One recording session featured about 10 minutes of Eric barking. “Then I had to listen to it all and choose which barks I thought were the best,” he said.

Virginia Virginal’s high-pitched voice was informed by Mrs. Doubtfire and Kenneth King’s by Kingston, who built the real-life version of that instrument — the same one Funaro commissioned. “He’s a Southern guy, and I might have exaggerated a little bit, but he does have a drawl,” Eric said.

The results are both entertaining and impressive. “How the lines synced up with the music was very important to me,” Eric said. “I spent months and months scrutinizing every syllable to try to get it just as musical as the harpsichord playing.”

Speaking of which, Funaro’s vibrant and sensitive performances — from William Byrd and Purcell to Edith Borroff and McLean — were recorded in the Duke University Chapel by Christopher Greenleaf, with whom she’s worked on 12 albums, most recently Uno, Due, Tre.

Andrea was working on a farm in Whidbey Island, north of Seattle, when she received a request that was not unfamiliar: She was wanted for a family project.

This would be a children’s book, The Harpsichord Diaries: A Musical Journey, adapted from Eric and her mother’s audio play. “They’re always finding one way or another to pull me back into the visual arts world,” Andrea said by phone from Port Townsend, WA. (Previous family projects had included Birth of a Harpsichord, a stop-motion film about the Kingston-built instrument.)

Andrea is now an independent animator and director, but back on Whidbey Island she was focused on her internship at the farm and enjoying working with her hands. “I wasn’t planning on pursuing art at all.” Still, she appreciated the nudge, and she couldn’t help being drawn in. “I could see how much the project meant to my mom,” she said. “We’re a very creative family, and it’s always fun when the stars align and we can work together.”

She would handle the illustrations, Eric would distill the 50-minute story, and their mother would write the haiku text. The trio arranged a week-long retreat at a cabin in Fort Worden State Park, near Port Townsend. “That was a pretty magical time. It really put a fire under the process and got it going,” Andrea said.

Funaro has been writing haiku for about a decade, ever since a rafting trip in New Zealand. “We’ve done a fair amount of travel,” she said. “I’ve performed on five continents, and Randy’s had a sabbatical in China. We’ve had very extreme experiences, and I’ve found that writing haiku is a way to concentrate visually and mentally on what’s going on.” The children’s book, of course, includes, “a lot of rhyming and a lot of fun words.”

After the retreat, Andrea spent six months on the illustrations. “I was working on the farm and living in a garage, and after work I would come home, make a plate of nachos, start drawing, and just work into the evening,” she said. “I loved the process. It was very meditative for me.”

The images are in watercolor, a favorite medium of hers from college, a time when she “wasn’t studying art per se” but was always trying to express herself creatively. Sequences of panels suggest the influence of graphic novels, though Andrea said that wasn’t a conscious choice. “I didn’t deliberate too much about the style. It’s just something that came very naturally to me.”

As did the high level of detail. “That’s something that comes out in my animation work as well,” Andrea said. “It’s like I can’t help myself, I just keep on adding lines on lines and eventually have to figure out when enough is enough.” Funaro loves that about her daughter’s work. “The stuff on her Instagram — oh my gosh, it’ll blow you away. It’s really incredible.”

Andrea pointed out the double spread of the 16th-century ballroom. “Sometimes the drawings are a little bit like Where’s Waldo? in that there are so many details to get lost in, and I think that one is a good example.”

For the character of Elena, Andrea chose big, bushy hair (inspired in part by her own) and charmingly oversized socks, which dip childishly over her toes. A white T-shirt and jeans help keep her in the background throughout her travels, where she is merely an observer. “We didn’t want her outfit to be too eye-grabbing,” Andrea said.

One of the most stunning images comes after Elena meets Kenneth King and begins to dance. She’s depicted abstractly, twirling amid the instrument’s decor, which Andrea translated to watercolor from Lisa Creed’s real-life design. “It just felt like a world in itself that could be explored,” Andrea said.

After moving past big-picture discussions, the project grew more difficult for Eric and Funaro. “What was hard was dealing with the minutiae,” Eric said. “We pored over this book at least 20 times with a fine-tooth comb and debated things like, does this word need to move over half an inch?”

As anyone with a family might expect, the dynamic wasn’t always sunshine and rainbows. “I would say that 80%, it’s awesome to work with your mom, and 20%, when you start to get on each other’s nerves, it’s worse,” Eric said, laughing. Overall, he loved it. “We were already very close, but it gave us something really exciting to do together.”

The project gave Funaro a view into why Eric is such a good director. “It’s because he sees the whole picture. His standards are so high, and it’s worth it. We can get frustrated, but we love each other, you know? We do. And it was a great experience.”

After all the creative work was done, The Harpsichord Diaries was shelved, stuck at the crossroads of publishing. “Finally, we realized that no conventional publisher was going to go for the oversized, hardcover book with beautiful, full-color pages,” Eric said. The family ended up self-publishing, with final book design by Dave Wofford of Durham-based Horse & Buggy Press.

“He got it,” Eric said. “He listened to the play, saw our prototype, and understood that I wanted something that was beautiful to hold — so that you couldn’t wait to sit with your infant child and turn the pages every night, over and over.”

The family unveiled the book at the Boston Early Music Festival. “We had a nice event,” Funaro said. “We rented the French Cultural Center, did a full run of the audio play, and had a French reception.” And they showed the video version of the book, which brings together music, sound effects, narration, haiku, and images. Eric hopes they can catch the eye of a traditional publisher who “will see the beauty of this, do a second printing, and help us get it to the bookstores.”

After the festival, and after so many years spent on The Harpsichord Diaries, Eric asked Funaro, “Mom, is it done? Have we finished?” They haven’t. Funaro proposed one last creative transformation, a version for live performance, and Eric knew she was right.

“Imagine,” he said, “that my mom is playing the repertoire live, I’m acting out these parts, and we have my sister’s illustrations projected on a screen. How could you not buy the book after seeing that?” The first performance is already lined up for Feb. 23 on the Mallarmé Chamber Players series in Durham.

He hasn’t expressed these exact words to Funaro, but for Eric, this has all been “like a love note for my mom.” The biggest gift he can give, he said, is to help her passion live on beyond her. Andrea agreed. “For me, it’s very much a family project, and it’s about wanting to pass on the appreciation for the harpsichord.”

Eric recalled a letter from one of Funaro’s colleagues, who said his kids had been reading the book again and again — and sneaking into the harpsichord room. “That’s the goal,” Eric said. “That is it, right there.”

Funaro put it most simply: “Long live the harpsichord!”

The Harpsichord Diaries: A Musical Journey is available for purchase online. The audio play, Elena’s Dream, can be downloaded or streamed for free.

Jarrett Hoffman is assistant to the editors at ClevelandClassical.com and served as a fellow at the 2014 Rubin Institute for Music Criticism. As a clarinetist, he performs in the Hudson Valley and New York City and runs a private studio.