This article can be found in the September 2022 issue of EMAg, the magazine of Early Music America.

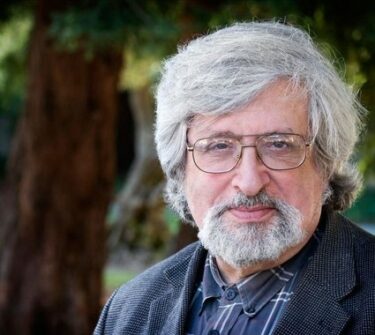

MUSINGS: On Richard Taruskin (1945-2022)

The recent death of Richard Taruskin has caused the earth to shake under our feet. Richard’s approach to music as an essential part of society, culture, and politics will forever affect our thinking. He could be authoritarian and some might have thought, at times, intentionally cruel. But he never lost sight of the high seriousness and invaluable place of music in the world. He appeared frequently in the pages of this magazine, often in forceful letters to the editor, back when it was called Historical Performance.

Richard and I were never close, but we had a long and amicable relationship. Although I do not feel competent to judge him, I’m happy to reflect, with sadness and admiration, on his titanic accomplishments. We might consider his two principal areas of interest—early music and the history of music. A third area should be added: Russian music, especially Stravinsky. (And perhaps a fourth: tendentious and wonderfully pugnacious musical journalism.) In a sense I feel I have been observing his taillights, and following them sometimes, for a very long time.

Imagine, in today’s multidisciplinary and fractal world, writing a five-volume Oxford History of Western Music all by yourself! And then “the Ox” winning you a second, and well-deserved, Otto Kinkeldey Award for best musicological work of the year? (Richard’s first Kinkeldey was for the two-volume Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions, cannily divided between the preparations and the performance of The Rite of Spring.)

Many of us in early music know Richard for his opinionated and provocative attacks on various aspects of the “movement” that he thought silly. Questions of authenticity, of “historical” performance, of playing the music as it was intended, often seemed to him folly. Others thought he was being obstructive.

His book Text and Act (1995), a collection of previously published essays, has been on everybody’s bookshelf, I think, for a long time. One of the papers, the one that has caused the most discussion, originally appeared among the 1988 published papers of a conference on early music held at Oberlin.

It contains the three-word damnation of early music that summed up, in a way, Richard’s approach: “People are dirt.” By this he meant—and here I oversimplify shamefully—that the successive generations of performers and performances in a piece’s history are like the successive layers of patina—or dirt—that “restorers” remove from works of art to show their original appearance. Equating the two—the restoration of art and the “authentic” performance of music—dismissed the artistic efforts of generations of musicians. I remember being consulted by the publisher about the advisability of publishing Text and Act, and remember advising them not to publish, since I hoped that Richard would write a self-standing book about early music that was not a collection of previous pieces. (Boy, was I wrong. And not for the first time…)

Richard Taruskin cared passionately about music. He was a virtuoso viol player, and the outpourings of remembrances from his colleagues are astounding. He could do almost anything; one favorite star turn was Thomas Morley’s rhythmic-acrobatic “Christes crosse be my speede.” Check it out if you don’t know it.

And he influenced generations of musicians and scholars in his Ogni Sorte Editions—wonderful collections of multiple versions of pieces on the same cantus firmus, using the same tune, etc. Many of these were the result of his serious research in preparing music for Cappella Nova, the singing group he led for many years in New York; the number of talented musicians who passed through the group over the decades is testimony to Richard’s ongoing contribution to our field. People are not dirt, after all, and the music was always central.

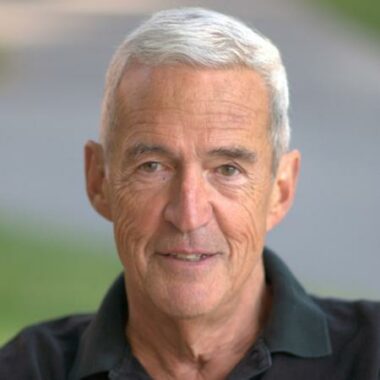

Thomas Forrest Kelly is Morton B. Knafel Research Professor of Music at Harvard. He previously directed early-music programs at Wellesley, the Five Colleges, and Oberlin. He is a past president and long-time board member of Early Music America. He is the author, most recently, of Capturing Music: the Story of Notation (W.W. Norton).