A portion of this article was first published in the January 2022 issue of EMAg, the Magazine of Early Music America. Nicolson died June 4, 2024.

James Nicolson is an American harpsichordist and virginalist. The only child of Jamaican parents, he started piano lessons at the age of four and studied at the Howard University School of Music’s Junior Preparatory Department. He discovered the harpsichord in his late 20s while living in Boston and went on to receive bachelor’s and master’s degrees at New England Conservatory. His passion led him to specialize in the keyboard music of William Byrd, and he shared his love of virginal music with thousands of people over his 25-year career in Europe. A well-respected and beloved member of the Boston early-music scene, he maintains a lovely keyboard collection and a private studio of students, and he serves as the president of the Cambridge Society of Early Music (CSEM). He was the 2013 recipient of EMA’s Howard Mayer Brown Award for lifetime achievement in the field of early music.

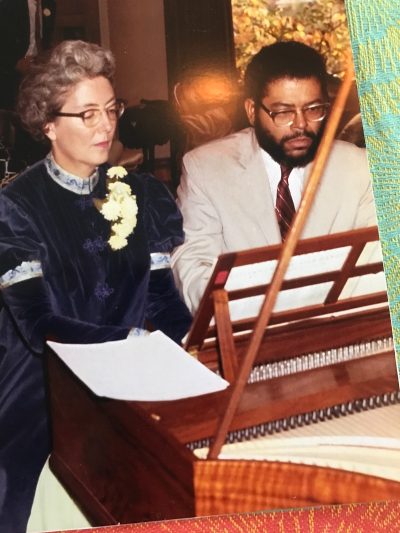

Nicolson was interviewed in March 2021 by Leslie Kwan, an American harpsichordist and the founder of The Monarch Network, a new-media production company that commissions and presents music-based digital content exclusively in support of hospital staff, patients, and their families at National Health Service hospitals in the United Kingdom.

Hello, James.

Hello, Leslie, how are you?

I am well.

How are you managing?

Well, London is still on lockdown, but I’m grateful to be healthy and to have a roof over my head.

Yes, the pandemic has been tough, and we have to be grateful for what we have, that’s for sure. How are things going with your music series?

We’ve been on hold because hospitals have put all volunteering on hold until the virus is under control. So in the meantime, I’ve been focused on fundraising, which has been interesting in this climate. As you know, fundraising is a long game, and this past year has revealed how that strategy needs to change and why. I took a look at the CSEM website, and the element of service to the community really resonated with me, especially during these unpredictable times. I was talking about the role of music in service of the community with a couple directors here and how presenting digital concerts can help shape the messaging of service post-lockdown.

Well, the question I keep thinking about is: “Will live concerts return as they were, pre-pandemic?”

Yes, that is the question of the year.

Speaking from the perspective of someone who is aging (88), I am pretty happy to sit at home and listen to music through the internet with a good pair of loudspeakers. I’m even happy not to have to produce live concerts because it’s a lot of work and very expensive. I think one of the benefits of the digital age is that I don’t have to move my body, and I can enjoy this on the screen. I wonder if people are going to take themselves out of the “pandemic mode” and get back out in the world. I think it’s going to take a lot of campaigning for people to come back to concert halls to the extent that it was before the pandemic. There’s a little secret: Even fundraising for digital is easier than for live events right now.

But you lived through that arc, and I think that’s wonderful. Your perspective is so much richer, James, compared to my generation. As someone who moved around different countries and moved your instrument physically presenting concerts, you’re probably exhausted just thinking about it.

Oh, yes! But I’ll tell you what brought my career to a stop. It was because of two things—the fall of the Berlin Wall and the fact that every time I would go through an airport, to and from Europe, I had to physically manhandle my instrument myself through airport customs. It meant that I couldn’t even get the use of a dolly.

Why not?

I had to go through customs first and get to the door leading to the outside. I didn’t have a dolly to use, so I had to drag my instrument across the floor. The impact of that physical experience was occurring when I was already in my 70s. The consequence would appear about five days after I would either arrive in Europe or back in the U.S. I would get hit with a lumbar attack down my lower back and in some cases would need to get a cortisone shot to relieve the pain. After about five years of that ritual, combined with the fact that economic conditions were getting harder and the local arts communities in Germany weren’t getting the same level of public funding as they had previously gotten, I needed to face a changed reality. Dates were harder to get, musicians were coming in from Eastern Europe who had been kept out by the Berlin Wall for so long, and they were eager to get to the West and eager to play. You could get a chamber orchestra to come play for pennies on the dollar. So, there wasn’t enough money to come in and support my activities to cross the Atlantic back and forth. I had to make a decision that life was changing and getting shorter. So I had to give it up.

How did that make you feel—to give it up for that reason?

Well, I had responsibilities here to take care of, mainly with my own students, which was a number that was shrinking anyhow. Although, curiously, I was left with my two very best harpsichord students, both of whom I still teach. So it’s been a very graceful drawdown for me. I haven’t felt bad about that. Life is always going to present you with an opportunity for change. You can’t avoid change; it’s going to happen. You might as well embrace it with all the skills and talents you have. It’s rather hard to reinvent yourself, but you can make modifications, you can find other pathways to take. The digital equipment is quite interesting, although it isn’t so easy to capture the sound of the harpsichord. It doesn’t always satisfy the ear as it does live.

What about how the fall of the Berlin Wall changed your ability to get gigs?

Each town in Germany belonged to a local arts council. The Germans were very good about bringing cultural experiences from all over. But the government allows only so much money to spend as they choose, so I don’t know if the people managing the councils had the best taste, but they knew what their audiences could absorb. I was fortunate to have a lady who was an agent for me who had contacts and promoted me.

Do you remember her name?

Her name was Barbara Röntsch. She was one of several people who helped me during my 25-year career through Germany. I always managed to get the use of an automobile to travel. I had contacts who would find a bed and breakfast for me. I had a much better experience with their help than if I was doing it myself! The fact that I was working very hard at speaking the language was a huge asset because when you address people in their own language, they are much happier to work with you. I never got a gig in Copenhagen. I didn’t try too hard because my Danish contacts were rather few. However, one thing I discovered was that even the local pushcart vendors in places like Germany and Austria were more responsive to my music-making.

What came first for you? Was it the love of the culture or love of the music that led you to Germany?

German was the one language that I had some familiarity with from school, and in the Boston area, there were many people from German-speaking countries living there. It was a draw that I couldn’t resist. German is a difficult language, so the learning curve is kind of steep. But it has some advantages. If you can hear it spoken clearly, you can spell every word. And if you can remember to put the participle of a verb at the end of a sentence, you’ve got it made. When you start saying a long, complicated sentence, I would often forget what the verb I needed was, so someone in the audience would always understand my predicament and shout out what the verb was so that I could continue on. They knew where I was going! They were delighted that I was attempting as an American to speak to them in their language. It was a connection to the people in the audience more than anything else.

So where did music come into the picture?

Oh, gee, I started piano lessons when I was four. But unfortunately, I didn’t realize the benefits that my talent should have given because to the folks of my parents’ generation, music was not to be considered as grounds for a career. It was a social grace. Even when my parents would entertain at home—we had rooms large enough to entertain a group of people—my mother would have me play.

As the dutiful son.

And the thing was, the conversations would continue while I was trying to play.

Which is very annoying.

It just wasn’t ideal for making me see possibilities in music. My father, whom I respected enormously, considered me to be less than wise to choose a career in music. He let me know how he felt in no uncertain terms. So I had to get to a point where there was absolutely no other possibility for me except to go after music, whatever the rewards or lack of rewards would be. That was the main thing.

Do you remember how old you were when you came to that realization?

28 or 29. Now we are at the origin of my story. I got into Harvard, spent four years as an undergraduate there and flunked out at the end. I just couldn’t do the academic work. I was pursuing a curriculum in physical sciences, and that was because I didn’t know what other choice I had. I found myself a job in the little town of Woods Hole, MA, where they have a renowned oceanographic institution. While I was there, I had an opportunity to engage in music because the organist of the local Episcopalian church took an interest in me, and I took piano lessons with her. I was pretty much starting at the beginning again, but I developed quickly. At the end of my second year with her, I participated in her annual recital with the rest of her students. I was the only adult and male student present, and I played several Bach two-part inventions, and that started things up again. While I was at the institution, I assembled a library of tapes because every ship had tape recorders back in those days. An oceanographic research voyage would leave Woods Hole and would be very soon out of the range of FM radio, so the personnel had a hunger for music. So, I made tapes.

The original playlist!

Well, people would request music, and this was all classical music, too. It was kind of amazing. I had the blessing of the institution to do this on my own time after hours. So, naturally, that stemmed my own interest in music. I left the institution to return to the Boston area and try to get an education, because it was clear that without a degree, I would not be able to advance in any career. So I came back and took some math courses, managed to retake calculus courses that I had previously flunked, but this time I passed them and understood calculus. Then I took some electrical engineering courses, and I was pretty good at understanding that material. This was at night school while I was holding down a job. I was sort of bored with those subjects, and music came back into my mind. I signed up for piano lessons at the Longy School and got going again. So I was gradually inching into music as a full-time nourishment for me. Then I took recorder lessons from a German-American recorder teacher named Anton Winkler, who is the father of the noted harpsichord maker Allan Winkler, and I began to hear harpsichords a lot in Boston, and as I had started out on a keyboard instrument, I was naturally attracted. But for quite a while, these instruments to my untutored ear sounded like buckets of nails.

How funny!

But then one night, something magical happened to me. A friend named Lex Silbiger, then a physicist living in Cambridge, had a lovely William Dowd harpsichord that began to pull me out of the bucket-of-nails mindset. One night, Lex took me to a concert at Sanders Theater in Cambridge presented by the Cambridge Society for Early Music. It was being directed by a Harvard music professor, G. Wallace Woodward, known as “Woody.” He was the kind of teacher who was able to communicate his love of music and get you to love it, too. He had a program with three harpsichordists and a string orchestra. After the opening work, a Sammartini symphony, each harpsichordist played a set of solo harpsichord pieces, and then they joined together at the end to play the Bach Concerto for Three Harpsichords in C Major with string orchestra. I listened to all three of the soloists, and the one that I responded to was the only woman in the group, Helen Keaney, a theory teacher at New England Conservatory who worked with Daniel Pinkham. When Helen played the music of Frescobaldi, it was as if the windows of Sanders Theatre had been flung open and fresh air and sunlight poured in and, all of a sudden, there was light. I was just blown away by her playing—so full of life, vitality, and color. I was deeply moved. And I thought, “That’s the instrument I want to study.”

Do you remember what year that was?

It was about 1962. I walked around in a daze for a while, and during this time I built a small kit harpsichord. Kalman Novak, the acting director at the Longy School, where I was studying piano, was doing a bunch of children’s concerts and asked to borrow my harpsichord. And the harpsichordist was Helen Keaney!

Wow.

I got to meet her, told her how much I had been stimulated by her playing, and we became friends on the spot. The idea occurred to me that I could perhaps study this instrument, and she was at NEC, so she agreed to prepare me for an entrance audition. So, when I was 31 years old, I entered NEC as a freshman harpsichord major, if you can believe it.

I can.

It was the best decision I have ever made in my adult life—to go to NEC. I stayed for six years, earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees. I studied with Helen Keaney all the way through and worked with Daniel Pinkham as his graduate assistant, and the world of early music opened up to me. I got invited to the CSEM as a board member, and I’ve been with the Society ever since.

So you found your home.

I found the right instrument, the right area. Boston was a wonderful place to be. All of the harpsichord makers were right here in this city. The Von Huenes of recorder-making fame, who had been board members of CSEM, struck out to produce a festival known as…

The Boston Early Music Festival!

Yes, and I stuck with CSEM, and at some point, as people aged out, I got talked into being president of the organization, and I’m still doing that. I’ve forgotten how many years it’s been. It’s obscene how long I’ve been involved. It’s been over 30 years or more.

When you started your lessons at four years old, where were you living in Boston at the time? What happened after you started lessons? You must have stopped. What happened in between? You said your parents were from Jamaica. Did they land in Boston?

Oh, no, they met and married in Chicago, then moved to Washington D.C., where I was born. She died when I was 14 while I was a freshman in high school.

What a young age to lose your mom.

My father, the more conservative of the two of them, did not encourage me to think about the possibilities of music. He had other ideas in mind.

As was typical for parents from the West Indies.

That’s the way life was back then. These people lived through the Depression and saw artists go hungry. The only thing that kept some semblance of artistic life going here was the WPA, the Works Progress Administration, which funded a lot of public art through the 1930s. I can’t recall if they did a lot for music or not, but most musicians did not fare well during the Depression years.

Are you an only child, James?

Yes. Which explains a lot.

I don’t know. I feel like an only child versus being the oldest are similar as I’m the oldest of four. We share a lot of similarities because we are the first ones your parents cut their teeth on. We get the brunt of everything. Our parents really don’t know what to do or how to do it. So, all of their hopes, fears and dreams fall on you.

They are vested in you absolutely.

And it is an investment, especially for parents who move from other countries to start a new life.

Sure!

So you stopped when you were in high school?

Yes, I still played but I wasn’t studying seriously.

When you were little, did you play in church versus home? Where did you perform?

The annual recital in church was my only performance opportunity. My father was teaching dentistry at Howard University Dental School, so I took some lessons at Howard University’s Junior School of Music, and the concerts were held at the Andrew Rankin Memorial Chapel on the Howard campus. I have a photo from one of the recitals. I was one of many children, and the only boy. That’s the second time I played in a piano recital, so it wasn’t very encouraging for the development of a young keyboard player. All the best pianists were girls!

That’s remarkable.

I have absolute pitch, so when I got into NEC and took dictation, I heard and understood every note. I had no difficulty with that, so I was grateful at age 31 to be developing some skills. What was slowest to come was my keyboard technique. It wasn’t until 20 years later, when I was in my 50s, that I sat down and started to work on technical exercises to improve my skills. I was just a late bloomer.

But you found your way through, so you were in your 30s when you achieved that. What happened after you completed your master’s?

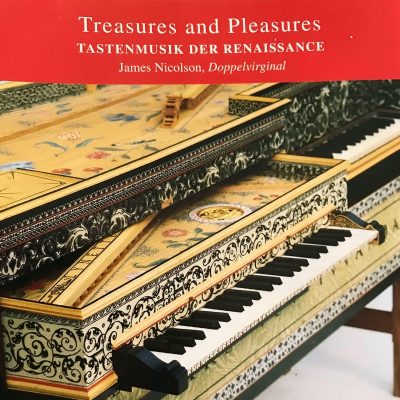

Well, I took on a few private students, a handful of them. I spent some time hanging around harpsichord workshops with Eric Herz and William Dowd. I managed to acquire a couple of harpsichords, and there was a demand for instruments to rent. This was the beginning of the rise of public performance on old instruments in Boston. That helped me keep body and soul together. I became adept at packing up instruments and transporting them to venues, so those technical skills helped. I also practiced a lot my great love, the keyboard music of William Byrd. My teacher introduced me to his music over many years. Afterwards, I made three recordings that contained “sins of youth” that marked my progress. I haven’t had a typical career at all. I couldn’t have, because I didn’t start working away at all of this early enough, but I was able to find my experiences, and it’s been a good run.

Do you remember the first Byrd piece you fell in love with?

Yes, it was a piece called “Lord Willoughby’s Welcome Home” in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book.

What was it about that piece that made you fall in love with Byrd?

Well, it was the one piece that I could, at that time, get my fingers around; that definitely helped! It was full of rhythm, flair, and I could hear the ceremonial elements. It is full of national pride and energy, even though it’s from the end of the 16th century! There are many character pieces in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book. There is a presentation collection of music by William Byrd called “My Ladye Nevells Booke.” There’s also the music of contemporary composers, too—Sweelinck, Frescobaldi, Morley, Bull, et al. I fell in love with this earlier period of keyboard music. That’s pretty much what my repertoire is, and then it all changed for the better when I got my copy of the double virginal.

How did you make the switch from harpsichord to the virginal?

It was out of a conversation I had with a lady named Lynette Tsiang, who made several early-style keyboard instruments. We had a conversation about what kind of instrument William Byrd would have had; we really don’t know what he had during his time. We came up with either a small Flemish single of four octaves or a virginal. Very quickly, I came to the decision to get one of the latter. Soon after Lynette had considered my order, I told her I was reading about a double virginal. Would she consider making one of those? And that’s what I ended up with. It’s a wonderful instrument. I have to say that modern harpsichord making comes from the idea that the maker will create an instrument “in the style of” instruments from a particular time and place, or even the work of a particular builder. So that’s the approach Lynette took. For the foundation of my instrument, there is a Johannes Ruckers virginal in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which, while I was going to NEC, sat in the Harrison Keller Room, where a number of instruments were stored. It was kept in a glass case—not playable, but it was there. Later on, Thomas Wolf, who was a student at NEC, restored the instrument while he was there. So that instrument is now in the Museum of Fine Arts, and it’s in incredible shape. When Lynette was working on my instrument, she used the acoustical layout of the soundboard from that instrument, and she also went to the collection at Yale to measure an orphaned child instrument made by Johannes Ruckers that originally combined with a mother. So, my instrument was designed from those sources. It’s charming from a visual perspective when the child and mother instruments are coupled. I ended up with a fabulous instrument which I love, with its deep resonance and its extraordinary timbre and sonority. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to interest any of my students in going in that direction. (Note: There are only 14 surviving original mother-child instruments known today.)

Was it this same virginal that you took with you on your tours through Germany?

Yes, it’s the same one. It travels very easily in a traveling trunk made for it, and it is quite easy to pack.

Did you ever play on it at customs to demonstrate that it was really an instrument?

Yes, in one place—on the border in the customs office between Austria and Czechoslovakia. I had to take it out, set it up, and play for the Czech border police. This was before they expelled the Russians, and then I also had to open the hood of the car to prove I wasn’t smuggling anyone out of the country.

It is staggering to me that you had to carry your instrument through customs without a dolly. I can’t process this.

Let me tell you. I had a dolly so I could disassemble and carry the instrument, but I couldn’t use the dolly to move the instrument about at first. I had to go through customs first, and only then could I use my dolly. I had to carry a document called a carnet de passage as a sort of passport for the virginal. This was before the formation of the European Union while the borders were still closed, and you had to negotiate your way over the border with the border police each time.

Did Barbara help you with your border transfer each time you went through this in Germany?

No, she didn’t have to. The carnet made it easy, but in some places the instrument had to be inspected. Nothing bad ever happened to the instrument.

When you finished your master’s degree, you started working with builders, developed your studio, and then you fell in love with the virginal. Do you remember how old you were when you took your first tour of Germany?

Yes, I started my first tour in 1985, so I was 52 years old. I was a late bloomer.

James, I am very happy to hear that because I think that when people set out in life to do whatever they’re supposed to do, they get caught up in what they “should do,” which is reinforced by parents and/or society. It really takes commitment to be yourself. I don’t see you as a late bloomer at all. My father— you and I have this in common—to him, the thought of me becoming a professional musician was just insane.

It was probably frightening to him.

Yes, because my parents spent—invested rather—hundreds of thousands of dollars in lessons, coachings, and instruments. I was fully immersed in it. Between you and me, we are different in terms of our training. But the unifying detail specifically about our fathers—having fathers who were immigrants and were creating a new life and wanted the best for their only child—you, the first born, and me, a girl. The thought of me pursuing music and not medicine—there’s no blueprint for being a musician. Your father had a blueprint as a dentist, but there was nothing for him to refer to for you, his only son. Hearing your story is so heartwarming. When I was 8 years old, I fell in love with Robert Frost’s poem, “The Road Not Taken.” I memorized that poem, and I honestly believed then, and now, that anyone who chooses to leave authentically always finds his way back. What’s been inspiring about your story is that you never wavered from your love of music. If anything, you were more committed to being yourself in a way that your parents couldn’t have dreamt for themselves. But also, you recognized that you only have one life. It is either you live it, or you don’t, and it didn’t matter to you how old you were, it’s just the fact that you got there. To me, that is a very inspiring lesson especially now during this pandemic, when so many musicians are terrified to reinvent themselves, as you said at the beginning of this interview. Not being afraid of change and just going with it has afforded you this beautiful life to travel to parts of the world you probably never imagined you would visit if you had not listened to yourself. Your life would not be nearly as colorful. To not have that moment, as you described so vividly, how the sun exploded, the windows opened when you heard the Frescobaldi. I think anyone who falls in love with this music can relate to that. Because it is an opening, it’s an awakening. I think as we get older, we’re afraid, really afraid to feel that emotion. We feel we should stay on this trajectory that doesn’t have the sunlight, the wind, or the color. You choose your life and this music that you fell in love with, based on how it felt for you. In doing so, you opened up—not just yourself but also your students—into a world that they probably would not have exposure to, and you’ve passed the baton to other people. And I think that’s the least that we could do if we’re open to being a vessel and alive. How did your father react when you decided to become a harpsichordist?

I think he remained skeptical. Let’s put it this way—he came to my bachelor’s recital, where he met a number of my friends. He was surprised I had such a lovely group of interesting people as friends, but he still considered it foolish to pursue a career in music. I couldn’t convince him otherwise.

There’s no convincing them, I know.

I recognized that I have to live my own life and suffer what rewards or deficits there are with making my own choices. As long as I could stay out of jail, I wasn’t doing any harm to society. So, I suppose I’m still using those guidelines to live by. My father, even up to his dying day, remained skeptical and couldn’t be convinced by any evidence to the contrary. One thing that gives me great satisfaction is the number of young people who have become professionals, and it’s really wonderful. It’s the way it ought to be.

I agree, and I get the sense your mom would have been on your side.

If she had lived, yes, she might have been on my side.

You knew yourself that there was something about music that made you happy, that was different from any other subject you were studying in school.

Yes.

But to be able to articulate that to your family, growing up in the 40s and 50s, to figure out your path as a young man, that was so different for your parents in Washington at that time—and for you to take on an academic pursuit that was out of the norm. I think that anyone that chooses to focus on art as their calling or work—it’s not viewed as being real, it doesn’t fit the construct of what a real job is during that time, like being a doctor, nurse, or dentist. It doesn’t have the trappings that come with having a job, particularly from a financial standpoint—the house, the car, the white picket fence, the kids. I remember when I was about nine years old when I had my own awakening that there was nothing else I would rather do, and I really didn’t know how it would come about, but I knew first and foremost I was a musician. So, for you, being open to that allowed you to have a career at a point where a lot of other people in their 40s and 50s would panic at the thought of starting at 50! I really believe because you were so in love with the music, you had a rebirth—you got to live again. A whole new life you probably wouldn’t have experienced if you had shut that out. If I’m talking out of turn, let me know.

No, you’re not. You’re making me feel very good because you have found value in my story, and I’m happy we’re having this exchange.

There’s one other thing I was wondering that you haven’t talked about. What was it like for you when you decided to shift gears and specialize in this music? Your career started in the 80s, which was a bit more integrated. You mentioned you were the only male student, but I would imagine you were most likely the only Black student as well.

Well, this may surprise you that I have not noted any experiences in all these years that I am aware of in which race has been an issue. I have literally not been subjected to any negative experiences because of the color of my skin. I haven’t had to deal with that sort of encounter. I think people don’t feel threatened by me in any circumstance.

It’s good to hear that you haven’t experienced this, because the topic of race has been a major conversation in early-music organizations. For too long, there hasn’t been an acceptance of the global majority in early music and in classical music in general. They recognize this needs to be addressed but are still reluctant to hire staff and artists that represent these communities, which in turn reflect the audiences they serve. The cognitive dissonance is staggering, and it’s a real problem for the future of early music.

The one thing I will say is that most of my performing has been in Europe. In America, most of the urban centers are hundreds of miles apart, whereas in Europe, there wasn’t any place I couldn’t get to within a day. After all, I was not an athletic young man, I was in my 50s! I would drive to each city, meet my host, set up the night before, and rest before the performance. I had to set up my instrument, tune it, perform, take it down, move it out, etc. I would need to have a decent store of energy to have available for each concert. So, it would have killed me to try to maintain that kind of routine in the U.S. I never had an opportunity for a racially tinged experience in the U.S. In Europe, I felt there was complete acceptance. It’s a wildly diverse place, so it doesn’t make sense that people wouldn’t be culturally appreciative.

I would agree with that. I had a similar experience when shortly after moving to Paris in 2017, a waiter asked me what I do for work, and I said, “I’m a harpsichordist.” He immediately wanted to talk about Rameau and Couperin! He was so overcome with happiness and that it happened every time I said “Je suis une claveciniste.” I think that once you try to speak the language, the citizens want to connect with you. It’s nice, especially in a country where the native language is not English, to have a conversation and to be able to say, “I love German music, German culture, and this is why I’m here.” I think appreciating their culture and working in it makes a world of difference. Now it makes sense to me why you may not have had any experiences like that since your career was in Europe. You were very fortunate.

Yes, I was.

I really love the way you described Frescobaldi’s music—it is very much like sunshine. And you said you had perfect pitch, which must have been fascinating. Did it bother you when you had to learn Baroque pitch?

No, it took a little getting used to. There was a period of confusion and, curiously enough, I tuned my harpsichord down to 392.

Ooooh, French Baroque pitch!

There’s a practical reason for that, Leslie. Lower pitch causes less stress and strain on the case, and the sound is juicier.

Would that mean you would play Byrd at 392?

No, not necessarily. It seems that pitch in England around that time might have been at modern pitch anyway. I don’t know what the jury is on that conclusively, as organ pitch was always a local affair. When you start pulling pitch up, there comes a point where the strings start breaking.

I love that you say that the instrument sounds juicier. The first time I heard Rameau at 392 was through a performance by my teacher, Arthur Haas. The first time I heard him play Rameau at that pitch, I felt that someone had given me a velvet blanket of the deepest mohair, and the sound sat in my solar plexus, I couldn’t shake the vibration of it, and I remember thinking, “Well, I need to play French Baroque music,” because it resonated with me in a way completely differently than the other periods. It just felt so good.

Well, yes it would! How wonderful to have that experience.

It definitely was. James, I think we have covered a lot in this interview, and this has been such a joyful exchange. You have given me a huge gift today.

Well, sharing my past with you has been very joyful for me, too! You stay healthy and keep alive.

I wish the same for you. It’s been wonderful.

The pleasure was mine.

Take care.

Bye bye!