by Curtis Pavey

Published January 2, 2024

The latest installment of EMA’s Early Music: the Americas explores the life and impact of Cuba’s ‘first and greatest’ musician.

Cuban composer, priest, and pedagogue Esteban Salas y Castro left a vast output of music, including over a hundred liturgical pieces. “Stylistically, Salas’ works employ a Baroque musical language which was typical in Latin America during the Colonial period,” summarizes the DEI-focused New Muses Project, “although his villancicos, or Spanish poetic and musical works, portrayed their own style as a result of the influence of Indigenous and African musical traditions.”

Lisa Lorenzino, in her essay “Esteban Salas and His Legacy of Music Education in Cuba” (Journal of Historical Research in Music Education, April 2013), describes him as a “humble priest now considered to be Cuba’s first native-born art music composer” and that he is “known throughout Cuba as the founder of a lineage of musical excellence.” One general-interest website, Cubanos Famosos, goes so far as to call Salas “the first and greatest classical Cuban musician.”

Yet the high quality of Salas’ music and his esteemed reputation are not well known outside of Cuba and the Spanish-speaking world. IMSLP lists just 17 works, a tiny fraction of his output. In this short article, part of EMA’s Early Music: the Americas series, I hope to spur publication and performances of Salas’ music and stimulate further research into this important composer’s life and works.

Born in Havana on December 25, 1725, he spent much of his life at the eastern end of the island, in Santiago de Cuba, where he worked as a music director and priest at the Santiago cathedral until his death on July 14, 1803.

Born to parents from the Canary Islands, Salas grew up in Havana and began studying music at age nine. (There is no confirmed description of his appearance or family background.) Initially, he learned to play the organ and violin in addition to singing in a church choir in Havana, and later received lessons in counterpoint and composition. Salas may have also studied with Cayetano Pagueras, a Barcelona-born musician well versed in the music of Europe, but information regarding his studies, like much else, needs further research.

At age 15, Salas enrolled in the seminary at the Universidad de Havana to become a Dominican priest. In addition to theology, he studied humanities and music. His university studies were cut short, however, by the early death of his father. In order to support his mother and siblings, he worked at the San Cristobál parish church (later renamed Cathedral) as a musician and composer. His rise as an important artist not only in Havana but also across Cuba led to his appointment at the Santiago Cathedral at the recommendation of Bishop Pablo Agustín Morell de Santa Cruz and the local town council.

Santiago de Cuba, currently a sprawling metropolis with just shy of a half-million residents, was an important port and cultural center in 16th- and 17th-century Cuba, known for copper, fishing, and agriculture. In the 16th century, it was the seat of the Catholic Church in Cuba in an era when many Catholic churches in Latin America were still directly controlled by authorities in Europe. This practice created a number of logistical issues, although by the time of Salas’ appointment in Santiago, decisions regarding the Church were increasingly made by town councils and local authorities.

Santiago de Cuba’s population featured a broad mix of people of both Spanish and African origins and, towards the turn of the 19th century — late in Salas’ life — this mix included French migrants who were fleeing Haiti during the revolt (1791-1804). The addition, and blending, of each unique segment of the population led to the birth of multiple important Cuban musical genres such as the son (or Son Cubano), the danzón, and more.

As noted, upon arriving in Santiago de Cuba, Salas took over the music directorship of the Santiago Cathedral. Among his duties were responsibilities to direct the church choir and orchestra, which originally numbered only 14 members. The ensemble included three sopranos, two altos, two tenors, two violins, one violon, two bassoons, harp, and organ. During Salas’ tenure, he requested and was granted increases in salaries for the musicians.

Along the way, he also expanded the ensemble, adding flutes, oboes, clarinets, horns, and violas. With larger forces he was able to enlarge the repertoire: they performed not only Salas’ works, but also fashionable European composers of the day, such as Haydn, Pleyel, Gossec, and music by Spanish and Neapolitan composers Francisco Melchor de Montemayor, Sebastián Durón, and Francisco Courcelle. In 1790, Salas was finally ordained a priest and served at the Santiago Cathedral for just over a decade before his death in 1803.

Rediscovered in a Cathedral Cabinet

Salas’ works were rediscovered in a cabinet in the Santiago Cathedral and later researched by a number of important Cuban musicologists and scholars. He wrote an impressive oeuvre of music, consisting mostly of masses and villancicos, but also including requiems, antiphons, hymns, lamentations, cantatas, pastorelas, passions, magnificats, and more. His villancicos are written for two, three, four or six voices plus violins, horn, oboes, and basso continuo; there are more than 30 in total.

Among the first researchers, in the 1940s, was Cuban writer and musicologist Alejo Carpentier. Carpentier’s novels such as Concierto barroco, La consagración de la primavera, and El arpa y la sombra feature musical themes and topics, demonstrating his lifelong passion for music. His important essay, La música en Cuba, served as an important outline of Cuban musical history because it discussed his rediscovery of Salas and his music in addition to music by other composers.

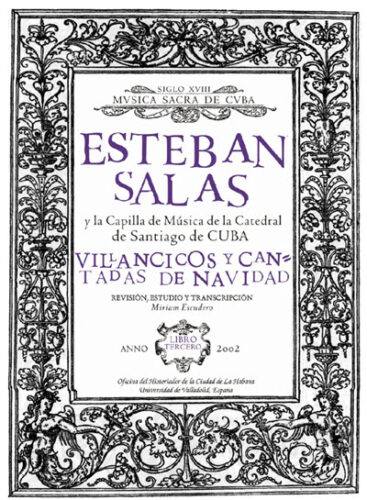

Other scholars such as Pablo Hernández Balaguer, musicologist and professor at Universidade de Oriente, have written extensively on Salas’ works, but these works were published in Spanish and remain largely unknown to English-speaking readers. Miriam Escudero Suástegui, a musicologist who studied at Universidad de Valladolid in Spain, studied and cataloged Salas’ music in her dissertation titled Esteban Salas y la Capilla de música de la Catedral de Santiago de Cuba.

In addition to scholarly works, a number of important recordings released in the last two decades highlight renewed interest in the music of Salas. Director María Felicia Pérez along with the choir Coro Exaudi de Cuba and the Benedictine Monks of Silos recorded multiple albums featuring Salas’ masses, villancicos, and requiems.

A similar historically informed recording by Teresa Paz and the Ars Longa de la Habana features Salas’ villancicos and cantados. The Orquestra Sinfónica Nacional de Cuba also recorded an album of Salas’ villancicos.

Despite the increased interest in Salas’ music, much remains unrecorded and in need of further advocacy throughout North America and beyond.

Salas’ importance as a composer and pedagogue in Cuba remains noticeable today. In Santiago de Cuba, the music conservatory — Conservatorio Esteban Salas — sits near the square of the city and continues to train over a hundred students each year.

Cubans nation-wide recognize Salas as one of the first native-born composers, and although that statement fails to take into account the colonial history of the island, Salas’ impact on the development of musical composition and education in Cuba is undeniable

Curtis Pavey is a pianist, harpsichordist, and educator serving as assistant professor of piano pedagogy and performance at the University of Missouri. He is a member of Early Music America’s Emerging Professional Leadership Council, helping spread awareness and passion for early music in North America. Early Music: the Americas is presented by EMA’s Emerging Professional Leadership Council.

Articles in this series: