by Sophie Genevieve Lowe

Published August 22, 2022

From Handel to George Washington, the British-American musician Rayner Taylor was a link from European traditions to American style and education.

Three thousand people pressed together at Westminster Abbey for a funeral on Friday April 20, 1759. Beloved composer George Frideric Handel was dead. During the service, the young boys of the Chapel Royal performed. Curious to see these events up close, a chorister from the Chapel Royal named Rayner bent over the open grave. Suddenly the boy’s hat fell into the hole, on top of the fresh grave of Handel.

Some three decades after that accidental connection with Handel, composer Rayner Taylor would board a ship for America and, by his training and contacts, bring to the cultural landscape of the nascent United States the highest levels of musical education and stylistic perspective.

Rayner Taylor was born in Soho, London in 1747 and baptized at St. Anne’s, the parish church of many French Huguenots. Rayner’s family probably originally came to England as refugees after Louis XIV’s revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. Though records are sparse, the Taylor family likely belonged to a theatrical family, and thus Soho, the center of London’s theatrical world, would have suited the family trade. (Not uncommon when researching census records and old directories, we find various birth years and different spellings. Based on advertisements he put in newspapers and on his tombstone, this article uses the 1747 birth date and Rayner to spell his name.)

Taylor was recruited to the Chapel Royal sometime before 1757, and was subject to the strict lifestyle imposed on the child performers. As Nicholas Temperly describes in his book Bound for America: Three British Composers, in addition to the Chapel Royal boys’ intensive training regimen, their music teacher would also hire the children out for concerts (sometimes even at the Italian opera house) for his own profit.

The Chapel Royal did however provide Taylor with a high caliber of music training and an understanding of the music world. Historian Victor Fell Yellin’s article “Rayner Taylor” (1983) observes that Taylor’s singing at the Chapel Royal put him at the epicenter of state ceremonies that include the funeral of George II (1760), the coronation of George III (1761), and perhaps most interestingly for our story, for Handel’s funeral in 1759. (Much of the background for the article comes from published works by Temperly and Yellin, among the very few scholars who have examined Taylor’s life and existing works.)

The bulk of the direct information we have on Taylor comes from Benjamin Carr, another British-American composer who knew Taylor well. Carr wrote of Handel’s funeral that:

“On this memorable and solemn occasion, his hat accidentally fell into the grave, and was buried with the remains of that wonderful composer. As Mr. Taylor’s higher works of composition are of the Handelian school, the following remarks of a gentleman to who he related this extraordinary occurrence, were highly complimentary: ‘Never mind, he left you some of his brains in return.’”

When Taylor’s voice changed, he left the Chapel Royal and swiftly commenced working as a harpsichordist, organist, vocalist, and composer. Notably, the 17-year-old Taylor was one of five singers featured in William Boyce’s Solomon in 1765. Taylor also performed the title role in a production of Thomas Arne’s (1710-1778) Artaxerxes at the New Theatre Royal in Edinburgh in 1769.

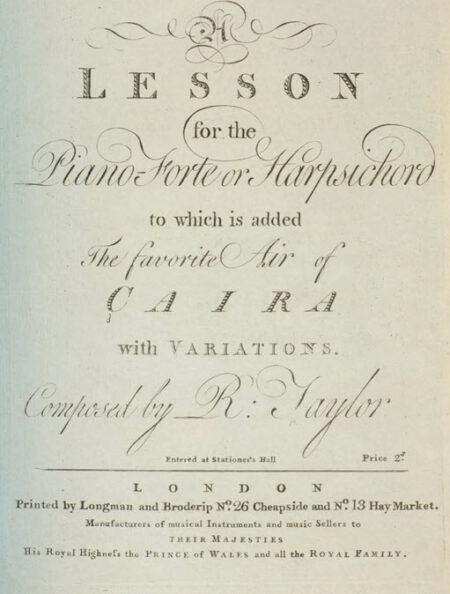

Taylor eventually worked in the Chelmsford, England parish as an organist and composer. One of his surviving anthems, “Try me, O God,” is derived from John Playfords Whole Book of Psalms. It was also during this time in Chelmsford that he composed Six Sonatas for the Harpsichord, Or Piano Forte, with an Accompanyment for a Violin, Opera Seconda in 1780. Taylor eventually resigned his post in Chelmsford and became the director and composer of music for London’s popular Sadlers Wells theater around 1784. Taylor became distinguished in the London music world, especially music theater, as a performer and composer.

During Taylor’s working years in London, he frequently appeared in newspaper articles along with more well-known composers. For example, on May 16, 1791 two advertisements in The Times announced a concert by Taylor and one by Franz Josef Haydn, at the height of his fame.

Taylor composed scores for various theatrical amusements, including the Royal Circus, although critics complained about his originality in composition for the circus instead of arranging well known melodies: “Though his music has merit, it is to be wished he would make more use of the old airs.” Despite this somewhat critical reception, Taylor’s time at the Royal Circus was an opportunity to negotiate his own musical ambitions with the expectations of public audiences. Experiences in this realm would prove particularly invaluable when the composer eventually set up shop in the young United States.

By the summer of 1792, Taylor had set his ambitions outside of London, and he sailed to the young United States. Whether it was a sense of adventure, an interest in the ideals of the United States, or perhaps an elopement with a certain soprano named Miss Huntley, it is clouded why a successful London musician decided to come to the relative frontier of America.

Whatever his reasoning, Taylor moved quickly into the American music scene and his first mention is an advertisement for a concert in Richmond, Virginia. The billing listed a “Mr. Taylor, Music Professor, lately arrived from London.” Taylor and Miss Huntley eventually moved to Baltimore, where he placed an advertisement to teach the “piano forte, harpsichord, etc.” He also became the organist at St. Anne’s Episcopal Church in Annapolis, apparently making a weekly commute from Baltimore. By 1793, Taylor had decided to move on to the acting capital of the United States, Philadelphia.

In Philadelphia, Taylor quickly advertised a “Nouvelle Entertainment, or Musical Extravaganza” where he and Miss Huntely performed. Shortly after he arrived, a horrific yellow fever epidemic hit Philadelphia causing even George Washington to flee the city. Whether out of compassion for the grieving families or seizing a financial occasion, Taylor composed a piece for the epidemic and gave it the title: “An Anthem. Suitable to the present occasion, for public or private worship.”

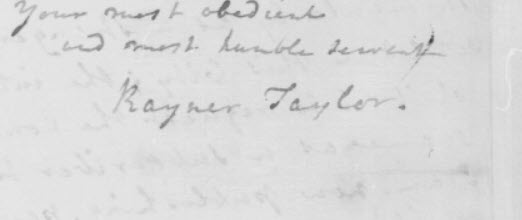

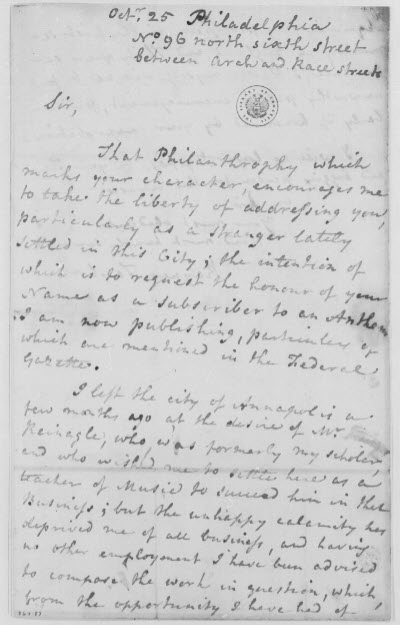

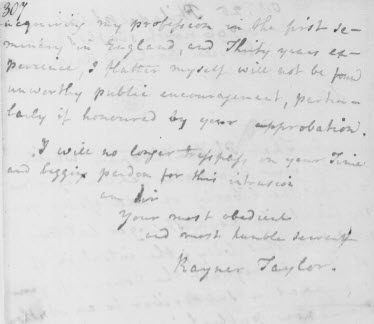

During this time, Taylor also wrote to George Washington. On October 25, 1793, he wrote:

“That Philanthrophy which marks your character, encourages me to take the liberty of addressing you, particularly as a stranger lately settled in this City; the intention of which is to request the honour of your Name as a subscriber to an Anthem I am now publishing, particulars of which are mentioned in the Federal Gazette.

I left the city of Annapolis a few months ago at the desire of Mr Reinagle, who was formerly my scholar, and who wished me to settle here as a teacher of Music to succeed him in that Business; but the unhappy calamity has deprived me of all business, and having no other employment I have been advised to compose the work in question, which, from the opportunity I have had of acquiring my profession in the first seminary in England, and Thirty years experience, I flatter myself will not be found unworthy public encouragement, particularly if honoured by your approbation.

I will no longer tresspass on your Time and begging pardon for this intrusion am Sir Your most obedient and most humble servant, Rayner Taylor.”

Washington kept the letter, but there is no known reply to Taylor.

Although Taylor composed chamber music that catered well to the growing musical marketplace (sonatas, popular arrangements, songs, etc.), his output also included larger-scale symphonic works specifically for public presentation. Two notable examples include a violin concerto by Taylor, which was played by George Gillingham with an orchestra in 1796, and another piece titled Storm Symphony, which was performed at the University of Pennsylvania in 1809.

One of the intriguing hallmarks of early American immigrant composers was compositional collaboration. A notable example occurred when three major players on the American scene, Raynor Taylor, Alexander Reinagle (1756-1809, friend of young Mozart in London), and Benjamin Carr (1768-1831, who studied organ with Charles Wesly and whose family was worked with the Playfords in the 17th century) all collaborated on the musical drama, The Wife of Two Husbands. These three composers, in addition to James Hewitt (1770-1827) are sometimes referred to as the American “Immigrant School.”

A week after George Washington’s death in 1799, Taylor collaborated with Reinagle on a piece titled A Monody. On the Death of the much lamented, the late Lieutenant-General of the Armies of the United States.

It is interesting to note how Taylor and Reinagle, even as post-war immigrants to the young republic, focused on Washington’s military reputation over his political post. One might be able to understand this as an effort by these composers to properly assimilate to, and even influence, the young country’s cultural landscape that was so tied to the American War for Independence.

Throughout his time in Great Britain and the United States, Taylor was constantly teaching. His teaching would have been particularly groundbreaking in the United States, where the caliber of music education he provided was unmatched. Consequently, his students would consist of a veritable “who’s who” of the early republic. Taylor taught the aforementioned composer Alexander Reinagle, for example, who then went on to teach Nellie Custis, Washington’s step-granddaughter. How many other Americans can trace their musical lineage back to Taylor?

Taylor enhanced his income by offering to copy music of “good stock, both vocal and instrumental” from his own library. This included music by Pleyel, J. C. Bach, and several of Handel’s Oratorios. The copies certainly would have been a critical source in introducing some of the European giants to a burgeoning American audience. Additionally, Taylor sold his own original compositions.

In 1809, Taylor became a naturalized citizen of the United States. He demonstrated his loyalty to his adopted country by arranging military music at Camp Dupont in Delaware during the war of 1812. During his time at the camp he produced his arrangement The Martial Music of Camp Dupont for piano and two flutes.

Till the end of his life, Taylor brought a wealth of information on performance practice to the Philadelphia Handelian Society. In 1815 he was able to still sing three tenor arias from Judas Maccabeus by Handel. On at least one occasion, he played a Handel organ concerto. Benjamin Carr reported that, “As an organist, he is second to no one. Any person acquainted with the true style of organ-playing, who has ever heard Mr. Taylor, will testify to this.” Alexander Reinagle, friend of Mozart who had also heard C.P.E. Bach testified that Taylors skill was “to be equal to the skill and powers of [C.P.E] Bach himself.”

Rayner Taylor died in Philadelphia on August 17, 1825 at the age of 78. Alone and destitute, his tombstone was erected by the Musical Fund Society of Philadelphia. Despite a lengthy career writing music for both the parlor and the playhouse, earning the esteem of his musical contemporaries, Taylor has since faded into obscurity. While much of his output has been lost, his sonata for violin offers a lovely and fresh insight into what we could be missing in pieces like the lost violin concerto.

Taylor came to the United States nine years after the American War of Independence, and he experienced the challenges of working in a newly independent economy. Because of its infancy as a nation and its fight to survive, the United State did not have the cultural and economic infrastructure to support performers and composers like Taylor—although today, in many respects, the situation isn’t so different.

In 1780, John Adams famously wrote to his wife Abigail:

“I must study Politicks and War that my sons may have liberty to study Mathematicks and Philosophy. My sons ought to study Mathematicks and Philosophy, Geography, natural History, Naval Architecture, navigation, Commerce and Agriculture, in order to give their Children a right to study Painting, Poetry, Musick…” – Paris, about May 12, 1780

Perhaps Taylor lived a generation too early. Though his legacy is not fully appreciated, he helped set the young United States’ musical course. The story of music in early America would not be complete without the study of Rayner Taylor.

Sophie Genevieve Lowe is a Baroque violinist and graduate of the Royal Academy of Music, London. In addition to performing, she is an avid researcher of music from Colonial America.

Others in the series: