by Ibis Laurel Betancourt

Published August 9, 2022

The composer’s high reputation but procrastinating behavior was good luck for posterity: the church forced him to catalogue his own music, then locked it away for safe keeping.

When the Cathedral of Puebla de los Angeles was completed in 1649, in what was then part of the viceroyalty of New Spain, ecclesiastical dignitaries came from as far as the Philippines to admire what one observer, Tamaris de Carmona, called “the greatest and most sumptuous temple that is known in the kingdoms of America, that without a doubt compete with the most distinguished and memorable temples in Europe.”

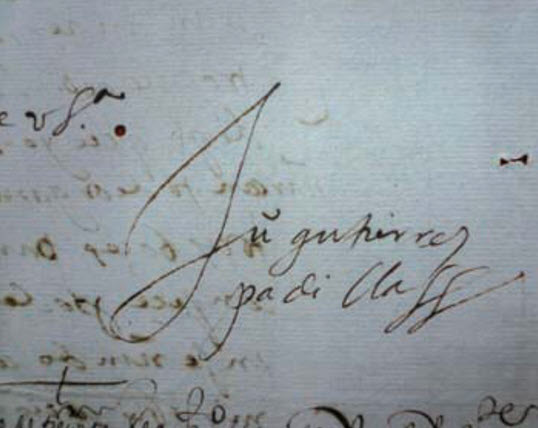

The Puebla cathedral was built with space for two organs, and therefore space for two choirs. Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla, perhaps the most prolific and important composer in Spanish Colonial America, spared no effort in composing mostly for cori spezzati, beautifully appropriate to such a grand space. This “broken choirs” technique can be heard in most of his compositions, paired with an intense use of textual iterations. His work Ego flos Campi, which was probably used in the 1649 consecration of the cathedral, exemplifies this style.

Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla’s most enduring music was composed in New Spain yet was soon performed across what’s now Latin America and Europe. He was also an instrument maker. Many of his students went on to become the leading musicians in Spanish Colonial America. (In the above Tamaris de Carmona quotation on the cathedral, and elsewhere in this essay, I used Robert Stevenson’s book Distinguished Maestro of New Spain as one resource. All translations in this essay are my own.)

Born in about 1590 in Malaga, in the Andalusian region of Spain, Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla had his father’s name, the son of Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla and Doña Catalina de los Ríos, both from Malaga. He began his musical career as a choir boy at the College of Saint Sebastian of the Cathedral of Malaga, where he learned plainchant and polyphony under the tutelage of then chapel master Francisco Vásquez (1586–1613). As early as 1606, he competed for chapel master posts in Malaga. Although he did not obtain a position with the Collegiate of Antequera, he eventually won the post at the chapel of Ronda where he remained for approximately four years.

In 1612, he moved to Cadiz and became chapel master of the Collegiate of Jerez de la Frontera for another four years as he worked diligently towards his next desired position—that of the Cathedral of Cadiz—where he worked from 1616 to 1622. Sometime around 1613, in the midst of this upward progression, Gutiérrez de Padilla, now ordained, also competed for a position at the Cathedral of Malaga but was beat out by a Portuguese musician, Esteban de Brito.

Soon after 1622, Gutiérrez de Padilla embarked on a journey across the Atlantic to New Spain. He arrived in Puebla de los Angeles, a bit southeast of Mexico City. For some 300 years, from 1532 till 1848, the vast territory of New Spain covered a shifting landscape that, at various times, included California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, Texas, Colorado, Arizona, parts of Wyoming, Kansas, and Oklahoma in the north, and stretched down to Central America (Guatemala, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Costa Rica), and even encompassed the Caribbean islands of Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Puerto Rico.

Upon arriving, Gutiérrez de Padilla looked for a position in the Cathedral of Puebla. Gaspar Fernandez, then chapel master of the cathedral, proposed and negotiated with the chapter (a college of clerics who advise the bishop) of the Cathedral of Puebla to hire Gutiérrez de Padilla as cantor and assistant professor. Gutiérrez de Padilla performed those roles until 1629—the year Gaspar Fernandez passed away—when he became the new chapel master at the cathedral until his own death in 1664.

As a student of Gaspar Fernandez, Gutiérrez de Padilla learned from and inherited some of Fernandez’s pioneering work in the New World. An important musical figure himself, Fernandez was born in Guatemala and composed the Cancionero Musical, the oldest known American codex found on the continent. This monumental work contains around 300 polyphonic pieces written mostly in vernacular languages (including Spanish, Castilian, Galician, and what was then called “lingua de negro,” a mix of Spanish and the dialects of enslaved people, many of them originally from West Africa).

The pieces contained in the Cancionero were mostly composed between 1609 and 1616 and, according to musicologist Aurelio Tello, stand “out for the finesse in style, the diversity of musical forms and genres, the solid technique exhibited, the variety of languages employed in the texts… revealing the cultural and linguistic diversity in New Spain at the end of the 15th century and beginning of the 16th century.” Tello considers the Cancionero to be the only collection found in the Americas equivalent to those of Renaissance Iberia.

Gutiérrez de Padilla was paid 500 pesos to serve as the cathedral’s cantor and assistant professor. This large sum hints at the enormous resources the cathedral of Puebla possessed, and is a testament of the esteem his employers held him in. His job, as stated in the records, was to:

…to sing at the chapel and elsewhere […] to conduct and assist the chapel master when he is unavailable or absent, to compose chanzonetas whenever requested, as well as to rehearse them with the singers, to teach plainchant and polyphony to the seizes and the choir boys and other people that have a Tiple voice suited for the Chapel and that are so needed and to compose the music for the important festivities.

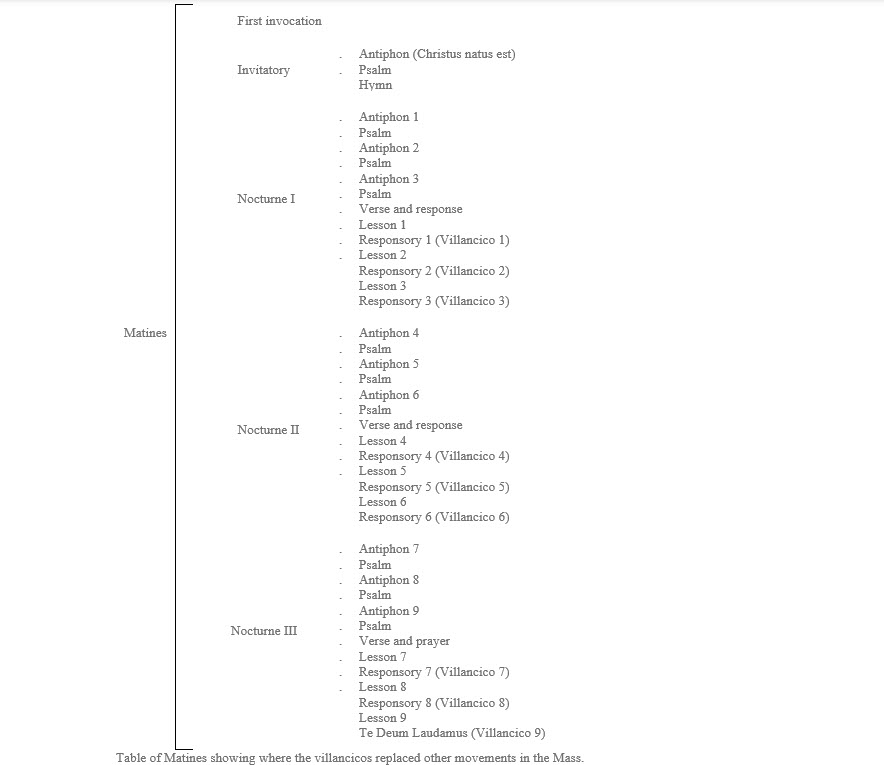

One of these duties was to compose the villancicos for the Matins (early morning church service), one of the liturgical calendar´s most important events, and to turn them into the archives every six months so they could be used whenever necessary. The villancicos were a very important and established genre in Spain and New Spain, containing texts in vernacular languages and incorporating elements of popular music making, some of them written as jácaras, ensaladillas, juguetes, negrillas, gitanillas, among other forms.

According to scholar Nelson Hurtado, in 1656 Gutiérrez de Padilla was not being diligent in fulfilling his obligations to complete all the required villancicos. Consequently, the cathedral ordered him to turn in, at once, all the villancicos from 1655 and those he had not composed from previous years. He was also commanded to make an inventory of all the music he owned. These works would then be turned into the cathedral’s steward and preserved under lock and key.

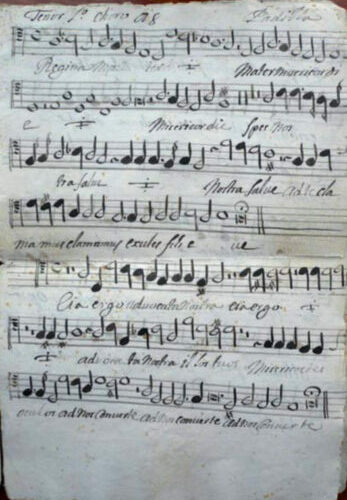

Thanks to this decision, and the fact that one year prior to Gutiérrez de Padilla’s death the chapter of the cathedral ordered to copy, restore, compile, and bind his music into a Libro de Coro XV, Puebla’s cathedral has preserved a large extent of his compositions. These include four masses, some motets, Marian antiphons, lamentations, passions, in addition to his eight folios of villancicos a 7 and a 8 (of which five of them are complete).

These sets of villancicos help us understand how these vernacular works were used in the celebration of Christmas and how they were incorporated within the Proper of the Mass in Matins—instead of the nocturnes—as part of the liturgical rite. Thus, in Spain and its colonies, chapel masters had the opportunity to showcase their compositional skills, and from the 15th century through the 17th century, according to historian María Antonia Palacios, “the villancico was the preferred vehicle for composers to transmit the zeal of Christmas.”

Having fives complete sets of Gutiérrez de Padilla’s folios, in their entirety (see chart, below) contrasts with the fact that so many other villancicos from other composers of this period have not been preserved as complete sets, but rather as single pieces. This thwarts the possibility of placing them in the proper musical and historical context in which they were composed.

Although the majority of these pieces were written and performed in Puebla´s Cathedral, there is information about some of these villancicos being performed as far as the cathedrals of Guatemala and Lisbon. Villancicos such as “Ah siolo flasiquillo,” “A la jacara, jacarilla,” and “Si al nacer o menino,” originally composed for the Matins in Puebla in 1653, were performed at the Royal Portuguese Chapel as well.

It is important to mention that Gutiérrez de Padilla lived during an exceptional moment in the history of New Spain, specifically in Puebla de los Angeles, as the city’s religious power was unmatched.

This was so much so that, as scholar Robert Stevenson writes, Puebla “was in touch with all the principal music centers in the colony; and music acquired during the regime of Gutiérrez de Padilla included the masterworks of Morales, Guerrero, and Victoria, the trinity of [Iberian] peninsular greats during the preceding century.” Gutiérrez de Padilla’s compositional contributions began when he was assistant to Gaspar Fernandez and blossomed later in his life during his time as chapel master.

1639 would mark one the still-incomplete cathedral’s most splendid moments: King Felipe VI’s appointment of Juan de Palafox as Visitor-General of New Spain and Bishop of Puebla de Los Angeles. Palafox, as Stevenson notes, “became a powerful legislation source that affected the musical aspects of the cathedrals and leading educational institutions where music was present.” He funded several churches and created the Palafox Library, donating 5,000 books to its collections.

The growth of musical activity flourished so much with Palafox’s presence that, by 1645, Gutiérrez de Padilla was overseeing 14 choir boys and 28 cantors, who sometimes doubled as minstrels. Some of these musicians would go on to be major musical figures of New Spain, such as Francisco López Capillas, a notable dulcian player and chapel master at the Cathedral of Mexico.

In the midst of this musical golden age, Gutiérrez de Padilla is also known for having an instrument manufacturing shop in his home that, as Alice Ray describes, was “selling as far afield as Guatemala and Venezuela, with the aid of Negro helpers during the early 1640s.” It is also possible that Native musicians from Huehuetenango (Guatemala) were obtaining their instruments from him.

Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla’s influence and appeal continue today, with many recordings of his music from an international roster of ensembles. Research into his life and his world is only beginning.

Ibis Laurel Betancourt is the founder and artistic director of Camerata XXXI, an ensemble dedicated to exploring the colonial music of the Americas. She loves reading and researching the intersection and roots of folk/popular and early music.

Others in the series: