by Ashley Mulcahy

Published July 11, 2022

In his book America’s Musical Life, musicologist Richard Crawford writes, “the main fact known about music making in early American homes is that it took place.” Today, the state of Massachusetts is full of skillfully preserved 16th- and 17th-century homes that serve as a visual point of reference for the imagination as we consider daily life in centuries past.

But “what did life in these homes sound like?” is a more challenging question. It’s fascinating because the traditional method of identifying composers and their connection to a specific place and time will not get you very far.

Instead, it’s a question that requires a look into the lives of ordinary musicians who haven’t been written into history.

One Massachusetts music-maker about whom we know more than most was the Reverend Peter Thacher. Born in Salem in 1651, Thacher came from a family of English Puritans. He moved to Milton, just south of Boston, in 1680 and preached there until his death in 1727.

Thacher played the viol as a social activity. We know this from an entry in his 1681 diary, where he recounts an evening spent with a group of men who had earlier helped him cut and cart wood: “There was 11 carts, 18 cutters of wood. I made supper for them. Wee had the Viol afterward.”

Thacher played an active role in the day-to-day lives of his congregants, and it seems that music was one way through which he fostered community.

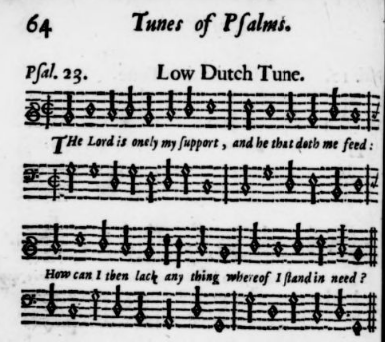

What might Peter Thacher have played on his viol? Like a number of other Puritan reverends, Thacher became an advocate for a more uniform method of psalm singing known as “Regular Singing.” In this method, the congregation sings from musical notation rather than by call and response. While instruments were forbidden in congregations like Thacher’s, primary sources suggest that Puritans recreationally accompanied psalms with instruments at home. For example, an entry in the diary of Massachusetts Puritan judge Samuel Sewall suggests psalm accompaniment on a bass instrument: “I, my wife, Hannah, Elisabeth Joseph, Mary rode in the coach to Muddy-River…Gates and her daughter Sparhawk sung the 114th psalm. Simon catch’d us a bass.”

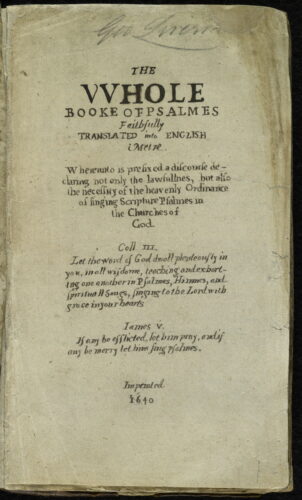

The year of this diary entry, 1698, is of particular interest, as it was in that year that the Ninth Edition Bay Psalm Book was printed in Massachusetts, making it the first book that contained musical notation to be printed in England’s North American colonies. The inclusion of bass lines in this edition serves as further evidence that Puritans like Thacher accompanied at-home psalm singing with instruments.

The psalm tunes and bass lines in this edition were lifted from Playford’s A Brief Introduction to the Skill of Musick. Playford dominated the music publishing industry in 17th-century England, selling commercial music books from his shop in London. Among Playford’s publications were many volumes of songs for voice with specified bass viol accompaniment.

Might Peter Thacher and his wood-chopping companions have played music published by Playford? While we lack documented examples of specific pieces that were played on the viol in colonial Massachusetts homes, we can infer from surviving primary sources that some viol players owned sheet music that was published in England and brought to the colonies.

Consider an advertisement from a 1716 issue of the Boston Gazette that reads, “This is to give notice that there is lately sent over from London a Choice Collection of Musickal Instruments Consisting of…Bass-Viols…Bows, Strings…Books of Instructions for all these Instruments…” While there is no specific mention of Playford’s volumes in surviving Massachusetts documents, the fact that two Playford publications are known to have been present in another English colony, Virginia, makes their presence in New England all the more likely.

Though Thacher’s December 6, 1681, diary entry is the only documented account of viol playing in the Thacher house, it seems unlikely that this was the only day in which the home was filled with the sounds of the viol. How might others under the Thacher roof have participated in making music?

What about Thacher’s wives—he married three times—and his children? We don’t know if they learned the viol. Yet documents like a 1764 issue of the Boston Gazette that advertised “a six-string bass viol for a girl” makes clear that women in colonial Massachusetts did play the viol. This is not surprising: several sources show that women in 17th-century England played the instrument. Since England and New England were highly interconnected, we can assume that women in colonial Massachusetts were playing the viol long before this 1764 advertisement was printed.

And what of the enslaved Native American and Black people who were also part of Thacher’s household? While we have hints of Thacher and the viol through his diary, most of the viol owners of colonial Massachusetts are documented through probate records, which only list the property of “heads of household”—almost exclusively white men. Several enslaved people (named or unnamed) are inhumanely listed as property in probate records, along with the instruments they played, mostly violin and trumpet. This proves that enslaved people were also contributing to the musical culture of colonial Massachusetts.

And still we ask the question: What did domestic life in early American homes sound like? Peter Thacher’s diary is indeed an important point of reference for the imagination. But given this importance, it is remarkable how little we actually know.

The answer demands that we consider the musical experiences of every sort of musician—including people like Peter Thacher, whose social status afforded entry into the historical record, and people who remain unknown because of their marginalized status. As Crawford reminds us, domestic music-making by colonial Americans remains an area ripe for exploration.

Ashley Mulcahy is a Boston-based mezzo-soprano and recent graduate of the Voxtet Program at the Yale School of Music and Institute of Sacred Music. In addition to singing with numerous ensembles, she co-directs her own voice and viol ensemble, Lyracle.

This essay is the second in a series. Early Music: the Americas is presented by EMA’s Emerging Professional Leadership Council.

Others in the series: