by Julia Dokter

Published April 8, 2024

Medieval Illuminations: A New Approach for Insights into Early Music

‘I happened to catch the light with the corner of my eye, and suddenly realized it was a dragon head!’

Gold. According to a quick online search, evidence for the mining and use of gold goes back at least 6,000 years. Humans have been fascinated by gold for quite a few millennia, and for good reason: It reflects light in rich, honeyed hues, imparting mystery in any application. To repurpose a famous line: They “that walked in darkness have seen a great light!”

This property of gold is one reason I started reproducing Medieval art, in all its beauty and quirkiness. To date, I have completed several pieces based on Medieval models, and the works I’d like to introduce are a combination of my love of early music and of visual arts — drawing, painting, and calligraphy. While I have studied music formally, and perform and teach professionally, I have also “messed around” in the visual arts for a long time.

But only recently have I combined these activities by re-imagining Medieval art that references music. I find that drawing or painting early instruments — as well as early-music notation, musicians, and images of musical philosophy — allows me to learn different things about the field than I would by researching and analyzing them in the usual academic ways.

Recently, for example, a student and I were transcribing into modern notation a previously untranscribed piece written in German organ tablature. There was a letter (indicating a pitch) that was unclear, and we were perplexed as to what it could be. Then I realized: Aha, of course! The scribe was using a broad-nib writing implement — similar to one that I use for calligraphy. And you can only make letters with such pens starting from above and pulling downwards. If the scribe was in a hurry, he either may not have finished the letter (i.e. forgotten to retake from the top) or tried to take a short cut and it did not work. When copying the same marking myself (in my head) with a broad-nib pen, I realized what letter it was and could complete the transcription.

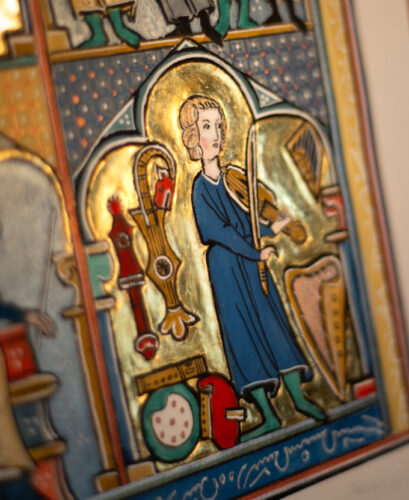

‘Lady Music’

My most recent work I call “Lady Music,” a reproduction of the famous set of panels depicting Boethius’ 6th-century formulation of the three kinds of music: Musica Mundana (top), Musica Humana (middle), and Musica Instrumentalis (lower).

The message behind these images in mostly encoded in Lady Music’s scepter and hands. In the upper portion, the scepter pierces cleanly through the panel’s barrier, almost touching the sphere representing the universe, communicating that true music is found in the Heavens (referring to the “Music of the Spheres” as formulated by Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle, and others). In the middle panels, her scepter barely makes it through the barrier, signifying that while she also considers this to be true music, it is less so: the addition of the irrational nature of the human body does not measure up to the pureness of Musica Mundana. In the lowest portion, Lady Music pulls her scepter completely back, switches it over to her “bad” (left) hand, and wags her right hand reproachfully at the musician: “What you are accomplishing there is only a semblance — if one may even go so far — of the pure of music of the Heavens.

The original set of panels can be found in a volume (Plutei 29/1) held in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, dated to the 14th century. If you know what the original looks like, you will understand why I call this a “reimagining” rather than a “reproduction.”

First — and possibly least important — my piece is much larger than the original (as is the case for all my reimagined pieces). The library information lists the original as 160mm x 230mm. The image itself occupies about two thirds of the page. My re-imagination, however, measures approximately 360mm x 220mm. The paper itself is still larger.

Second, the original is — as far as I can tell, since I have only seen it digitally — only in matte paint. I decided to add both metallic paint and 24k gold leaf in certain areas. This makes the piece really glow with a three-dimensional feel.

And finally, the original manuscript seems to show either damage or incompleteness. For example, while I was sketching the end of the curved fingerboard or pegbox embellishment (that is what I assume it is) of one of the citoles, I could not decipher the image. But then I happened to catch the light with the corner of my eye, and suddenly realized that it was a dragon head! (I may have let out a squeak of excitement.) So that has been re-imagined, filling in the blanks and making the pointy-eared dragonhead more recognizable.

Like my other illuminations, ‘Lady Music’ has its own page on my website.

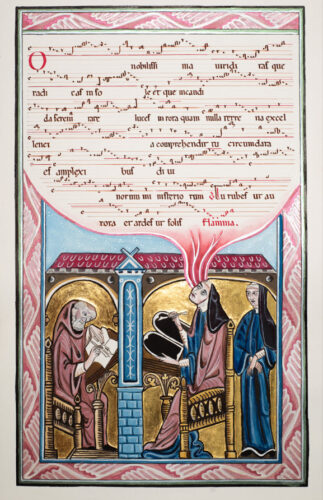

‘Hildegard and a Vision of Music’

Hildegard. What more can one say about this incredible woman? As soon as her name is mentioned, in whatever context, my inner voice immediately exclaims in awe over her ecstatic musical outpourings. She absolutely needed to be done in some form or other.

I decided to combine two manuscripts for this piece: The musical text, O nobilissima viriditas, is found in a massive, 481-page volume (Hs.2), dated to ca. 1180-1190 (?) and housed in the Hochschul- und Landesbibliothek RheinMain. The piece is part of Hildegard’s Scivias. The bottom image was taken from the Liber Divinorum Operum, dated to 1210 according to the Library of Congress.

This was a curious image to make.

First, the digitization of the original seems to show places where the gold leaf has rubbed or flaked off, and the substrate is showing through. This means that, at least in my imagination, I was able to “restore” the gold leaf. Of course, the image is not identical with the original since I freehand everything (and I do not possess the skills of a master forger!).

Second, the upper portion is actually the first time I have ever written neumes. I asked myself why that was the case, and found that I could not answer it. Part of the reason is that the usual goal is to transcribe — not recreate! — original texts in university paleography classes.

The gold leafing technique for both “Lady Music” and “Hildegard and a Vision of Music” was complex and labor-intensive, where I laid down multiple layers of gesso (rabbit skin glue and whiting), sanding in between. Then I laid down multiple layers of clay bole (mixed with rabbit skin glue). This is the traditional substrate for gold leafing, as it allows you to take an agate stone to burnish the gold afterwards. This is what creates the enormous shine.

For more on ‘Hildegard and a Vision of Music’ visit the webpage devoted to this image.

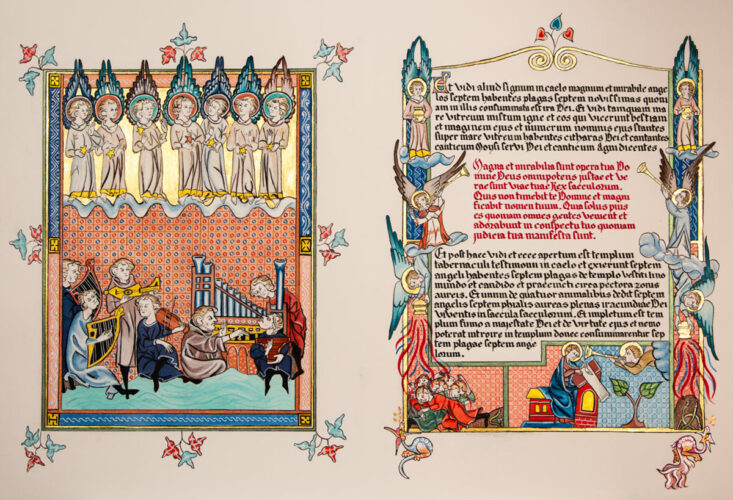

‘The Seven Angels’

This piece was a joy to work on. It is quirky, has an enormous amount of rather amusing elements…and DRAGONS! Because, besides the gold, we look for dragons in medieval iconography, right?

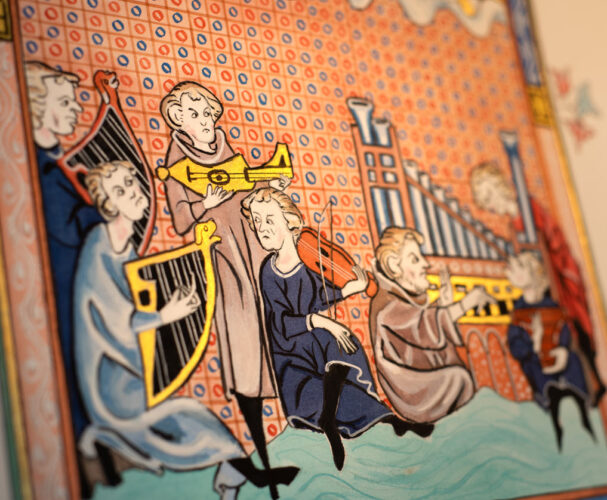

I based my re-imagination on images found in the famous 14th-century manuscript (Français 13096) housed in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. This is an astonishing manuscript, replete with many full-paged gold-leaf illuminations. I was immediately drawn to the image on the left side of the picture below not only because of the depiction of the organ, but because of all the other instruments: harps, psaltery, citole, vielle.

The left side picture is a fairly faithful reproduction of what you will see in the original manuscript. However, I changed the text side. The original is in French, but, as you see, I have provided the text in Latin. Nevertheless, I tried to use the same script as found in the original. I also provided figures I found throughout the rest of the manuscript and placed them around the text to illustrate the story.

The text is taken from Revelation 15, in which there is a substantial portion devoted to a song (which I’ve given in red ink). There are also references to musicians.

The amusing parts of this piece are in how the elements of the text are captured. The text speaks about the seven angels who dispense plagues on Earth. Normally, when thinking of angels, the images that comes to mind are the pretty, fluffy, lacy, serene angels found on Christmas cards. The angels depicted here are not far from that image with their beautiful wings. However, if you take a close look, they all have rather malevolent expressions on their faces. That made me chuckle.

Then I noticed the musicians also look positively terrifying, appearing as if they are about to commit some nefarious act!

On the right side of the illumination, at the bottom, you will notice angels dumping plagues on the poor sots below, complete with blood and gore. Cute dragons are eating the refuse caused by the plagues. I had to paint them in metallic paint.

And, finally, Français 13096 has many pictures of St. John receiving the visions he recorded in Revelation. I picked one where an angel has shoved its trumpet right in front of St. John’s face (lower right), apparently causing him substantial aural pain. Another chuckle.

For more about this piece, please see my website here.

I have plans for future pieces. For example, I have a line drawing already partly completed of a massively complex page in the Florentine manuscript (MS M. 653) with a huge illuminated “P” as the beginning of Puer natus est nobis.

Eventually, I hope to work my way up into more historical techniques, such as working on vellum, and using more historical pigments.

If you have any comments or queries, contact me or sign up for emails.

Julia Dokter earned a Ph.D. in musicology from Utrecht University and a D.Mus in organ performance at McGill University. A recipient of the American Musicological Society’s Noah Greenberg Award in 2013, she currently teaches at Baylor University. She is the author of Tempo and Tactus in the German Baroque (Univ. of Rochester Press), which was reviewed by EMA in 2022.