“It is certainly no exaggeration to say that Joan Benson is one of the seminal figures in the revival of the historical clavichord. Her career spans the chasm between the lightly strung revival instruments common in the late 1950s and early 1960s, to the awakened interest in historic (and thus historical) instruments in the 1970s and 1980s.”

So wrote Gregory Crowell, University Organist and Affiliate Professor of Music at Grand Valley State University, in his review of Benson’s 2014 book Clavichord for Beginners (Indiana University Press).

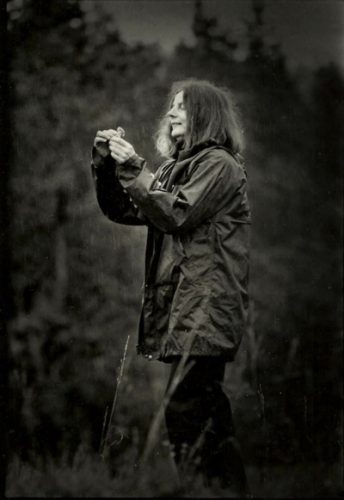

It was with great interest that I was able to meet Benson last year, on a particularly nasty November day in Eugene, OR, where she has lived for the past 25 years. Lashing rain and wind were bringing trees down, and she was concerned about the foliage in her sylvan neighborhood.

Nothing much will fell Benson, however. At 92, she is still tall and sinewy, with fine features that belie the fortitude that took her around the world as a pioneering clavichord artist at a time when women rarely traveled alone. Yet this swashbuckling figure was devoted to expressing the tender empfindsamer Stil on the clavichord, which is such a soft-toned instrument that her concerts were subtly amplified. She also added pianos of the 18th century to her artistry.

Benson lives surrounded by trees and the instruments that shaped her life: a 1795 Broadwood piano and a 1770 Viennese-action fortepiano. In her late 70s, she sold her beloved 1780 Swedish clavichord to John Barnes, former curator of the Reid Collection of Early Keyboard Instruments at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

Following an itinerant childhood and piano studies in college, Benson headed to Europe in 1953 to study with the Swiss pianist Edwin Fischer and take classes with Alfred Cortot and Olivier Messiaen. Her sensitivity to soft sounds led her, finally, to the rarely played clavichord. For four years, she studied with two of the few clavichord teachers of the era: Fritz Neumeyer in Germany and Santiago Kastner in Portugal.

The 1950s were a great time to be in Europe, Benson says. As the continent rebuilt itself following the Second World War, curators of instrument collections were eager to share clavichords with Benson, dusting off those that had been hidden away.

When it came time to return to the United States, Benson did so in inimitable style, taking a boat from Lisbon to San Francisco, as this appeared to be the only way she could stow two clavichords — on cabin bunks. Upon arrival, one instrument was slightly damaged, and Benson was directed to Stanford University to have it repaired.

Somehow, the repair turned into a faculty position and the beginning of her career as a keyboard artist.

Benson’s first recording, in 1962, was hailed as one of the best classical LPs of the year by Saturday Review. “I first heard Joan on that record in 1969 or 1970,” says Barry Phillips, a cellist and recording engineer who shared a Grammy Award in 2012 for Ravi Shankar’s album The Living Room Sessons Part 1. “From the first notes, I was hooked — not only the sound of the clavichord but her sensitive, sometimes fragile, sometimes bold-as-could-be performances.”

Through a friend of a friend, Phillips met Benson. “I was only 14, but I wanted to play the clavichord. I’m still amazed and thankful she took me on, pretty much as a beginner, and we worked through learning to read and learning clavichord technique at the same time. I remember Joan as a very flexible teacher — attuned to the student’s needs on that day. One day I was sort of hunched over the clavichord, and before I knew it we were doing some yoga.”

The yoga was hardly surprising, as Benson had discovered Buddhism in Palo Alto in 1960 with the Japanese Zen priest Shunryū Suzuki. “I was present for his talks — there were just 10 of us — that formed the basis of his famous book Zen Mind Beginners Mind. Later, after giving concerts, I would reward myself with solo Buddhist retreats. For example, after an East Coast tour, I stayed at Gampo Abbey with Pema Chodron in Nova Scotia. After a European tour, I spent 10 days with Thich Nhat Hanh at Plum Village in southern France.”

Benson needed the breaks after touring as a concert artist in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s through North America, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, including solo trips to Hong Kong, Lebanon, and Bali, where she heard the finest of gamelan playing. “I had no fear,” she says, “because I felt a common connectedness with everyone and an open-hearted delight in their different cultures.”

Marita P. McClymonds, Professor Emerita of Music at the University of Virginia, enjoyed spending time with Benson at conferences around the world. “I feel Joan should be honored for her consummate artistry within the confines of a disciplined, historical performance practice,” she says, “and for her dedication to the pioneering work of restoring the clavichord to the international world of music, and the courageous example she set, in pursuing a worldwide career as a woman alone in the mid-20th century.

“Joan’s particular contribution had to do with her determined efforts to combine what history had to teach with a personal commitment to take the performance of early music beyond the novelty and into the realm of profoundly moving emotional experience for performer and listener alike. Her performances have brought her international critical acclaim and brought this delicate and very challenging instrument onto the world stage.”

Back in the U.S., one of Benson’s students was Sandra Soderlund, who teaches clavichord, harpsichord, and organ at Mills College in Oakland, CA.

“I first encountered Joan when I took a clavichord and fortepiano workshop with her in the summer of 1974,” says Soderlund. “I was just beginning my doctoral program in keyboard performance practices at Stanford. I subsequently studied fortepiano privately with Joan and also worked with her on a major paper on C.P.E. Bach that was published in The Diapason. I enjoyed Joan’s sense of humor greatly.

“The thing that I particularly remember is one recital wherein she played a set of variations by Mozart on an especially sappy opera tune. She read the text of the song first and then sat down and played, expressing the wit in the piece so well that we were all overcome with laughter. It was a revelation! I learned that music, particularly of that period, did not have to be so serious.”

Fearsomely intelligent, Benson has explored new landscapes in music. “Joan Benson contacted me in the early ’80s for a new piece which could blend clavichord and computer-generated sound,” says Chris Chafe, Professor of Music and Director of the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) at Stanford University.

“The idea was very Joan in all ways: encouraging something uncommon or even untried, extending the instrument, using it for its unique qualities, and, above all, highlighting expressive musical potentials. This was the height of big loudspeaker systems being married to digital sound composition, and she was thinking of something on an entirely different plane. The result changed our practices in some significant ways, different for each of us, and those fascinations have endured.”

Benson claims she was born with a mystical sense, and it’s not difficult to feel you’re in the presence of someone rather special. There probably aren’t many other nonagenarians who stop playing in their 70s, spend eight years away from performance, and then return in their late 80s to write that seminal guide, Clavichord for Beginners.

William Mahrt, Associate Professor of Music at Stanford University, has known Benson since 1963 and says that her temperament was mediated by Buddhism, its stabilizing force serving the spiritual depth of her playing. “It is her extraordinary temperament that created this affinity for the free fantasias of Mozart, W.F. Bach, and C.P.E. Bach. When Joan plays them, they are truly ‘fantastic,’ in the original sense of the word.”

Phillips, her recording engineer, has just completed a two-CD collection of Benson’s recordings, using original source tapes of studio and live performances that span her career. In addition, he has unearthed some of her original Titanic LPs, on which she plays clavichords from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. “Audiences were often stunned and elated by the emotional impact of her beautiful playing,” Phillips says.

Sometime soon, prepare to be stunned.

“The Joan Benson Collection” will be available this spring on iTunes and other major download sites, to be followed this summer with the CD release.

Karin Brookes is Executive Director of Early Music America.