When COVID-19 restrictions were imposed in mid-March and in-person teaching came to a halt at Northwestern University in Evanston, IL, Hanna Bingham thought her dreams of performing violin in the school’s planned production of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo were over.

“I was so bummed out,” the third-year graduate student said, “because this would have been my last opportunity to play in a Baroque opera, and I really love to play in opera. I was really looking forward to it, and I was devastated: The school is closing, and we don’t know what is going to happen.”

But in a matter of days, the two Bienen School of Music faculty members leading the production decided L’Orfeo would go on, if in a very different form. To follow coronavirus protocols, it was transformed into a pair of films — the opera was double cast — titled Orfeo Remote that will be presented via five weekly “episodes” on YouTube after the holidays.

“I just recall that it was a fairly instantaneous decision that, ‘Yup, that’s what we’re going to do,’” said Stephen Alltop, conductor of Northwestern’s Baroque Music Ensemble and music director for the project.

The performances by the 40 singers and 20 players who took part in Orfeo Remote were filmed and recorded in and around their homes as far away as South Korea, and Alltop and Joachim Schamberger, director of opera, committed to editing the music and imagery into a cohesive whole.

The two knew the undertaking would be an ambitious one. But it has turned out to be a far more gargantuan project than either envisioned — a melding of some 1,200 video and 1,400 audio files.

“If I chose, I could work on this for the rest of my life. It’s endless,” said Alltop, who finished the audio editing in mid-August. “It was like what the settlers out West must have felt from time to time: I keep traveling, and there is no end in sight. And that’s how this was.”

The Northwestern Opera Theater was to present L’Orfeo, one of the three extant operas of Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643), during live performances last May. The academic company has presented several Baroque operas in recent years with support from the Evelyn Dunbar Endowment for Early Music.

And, indeed, by mid-March, many of the preparations were done. The 10 professional players, including members of the Dark Horse Consort, who normally perform alongside the student musicians had been hired. Auditions had been completed, and some coaching had begun.

Alltop and Schamberger could easily have elected to drop the production and just have students study their roles or musical parts. But because so much groundwork had been laid, the two decided it only made sense to move ahead, shifting the production to video and drawing on Schamberger’s dual background as both a stage designer and a video designer.

The two quickly got buy-in from the students, who were enthusiastic, though they probably did not fully understand the challenge in front of them. “We had to turn everyone in their homes into filmmakers on their phones,” Schamberger said. Most of them “had no experience whatsoever in how to create any film.”

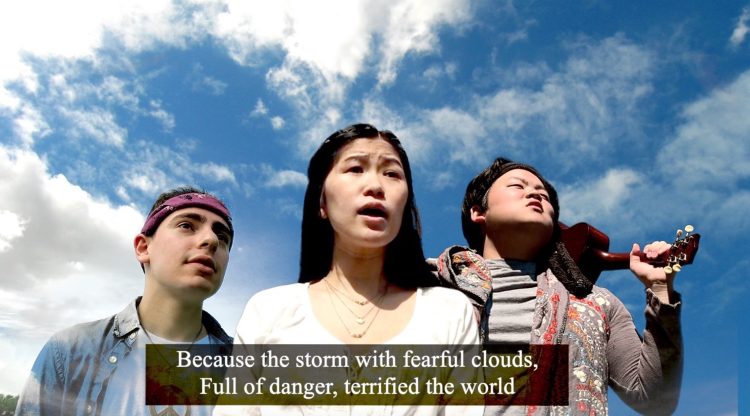

Unlike many online music performances during the pandemic that have featured multiple musicians spread across the screen in separate boxes, Orfeo Remote will be presented like a real movie, with only hints that each character was filmed in a separate location.

The singers performed their roles — lip-syncing to their own previously recorded audio tracks — outside either using a tripod to support a smartphone camera or involving family members as volunteer cinematographers.

In scenes where the performers needed to be shown together, Schamberger gave the singers specific notions of their body placement and the angle of the cameras, and he is merging the characters in the editing process.

Most shots are planned ahead of time in a normal movie, but the scattered nature of this production didn’t make that possible. “So there are moments,” Schamberger said, “where I gave people ideas and we discussed general things, and for the purpose of them having fun with it and the educational aspect, I let them play and be creative on their own.”

In this version of L’Orfeo, La Musica (Music), a kind of Everywoman who serves as narrator, acknowledges the present-day world of the coronavirus in her opening prologue. “This is what is so dear to me about this project,” Schamberger said. “It’s very much in real time, and it tells what happened to all of us as artists and musicians at this very moment.”

The character realizes that her school and much of the rest of the world has been shut down, and she rallies her friends to produce an opera on YouTube. Longing for a more carefree time, she picks the hippie world of the 1960s as the setting for the piece. “So, it’s like the story in the story, the theater in the theater,” Schamberger said.

The first of order of business for Alltop was recording the entire opera on his harpsichord and concert organ at home. He sent those recordings to other musicians, who laid in their parts, and the combined track was then sent to other players, who further built on it.

When Bingham, the violinist, got her recording, it featured Alltop and violinist Julie Andrijeski, one of the Dark Horse players. Listening to those tracks and watching a YouTube video of Alltop conducting, Bingham recorded her parts in an office at her family home in DeKalb, IL, using a smartphone she posed on a shelf.

The only significant problem came in the moresca, a kind of dance, that ends the opera. The audio track Bingham received was missing the click track (an accompanying set of audio cues), so she didn’t know where to come in. “We were all laughing about it at the end,” said Bingham, who posted a resulting blooper reel on Facebook.

By the time Alltop got to theorbo player Brandon Acker, the Northwestern alumnus received some of the most “polished tracks,” which already had the sounds of the singers and other instrumentalists. “I would grab my headphones and my recording gear,” he said, “and I would add my layer until I thought I got something that works pretty well, and then move on to the next excerpt.”

The advantage of this online approach, Acker said, was that he was able to fine-tune his performance, re-recording as he wanted. The downside was that there was none of the simultaneous give-and-take that is possible in live performances. “So, when I played something a certain way,” he said, “I had no liberty to inspire any change, so it was more about fitting into the puzzle than steering anything.”

For the vocal soloists, Alltop sent a recording of his continuo accompaniment and then coached them via Zoom as they sang to it, offering guidance in terms of style, diction, and embellishment. When they were ready, the singers recorded their performances and returned their tracks to Alltop, who re-recorded his playing, responding to their interpretations.

As the audio files were coming and going, the first big challenge was just keeping everything organized, and the second was combining all these recordings made on disparate equipment in different acoustics and at varied volumes into a cohesive whole.

At first, Alltop used GarageBand as his editing software but later switched to the more sophisticated Logic Pro X, getting pointers from Northwestern’s information technology staff and from Acker, who posts tracks regularly on YouTube. “The whole time, I’m getting an enormous crash course in audio production,” Alltop said.

Acker was astounded by the high quality of the film’s final audio track. “I was skeptical at the beginning and just blown away by the end result,” he said. “I think everyone will be surprised to hear that this was done, in many cases, on a phone by various people who sent it in.”

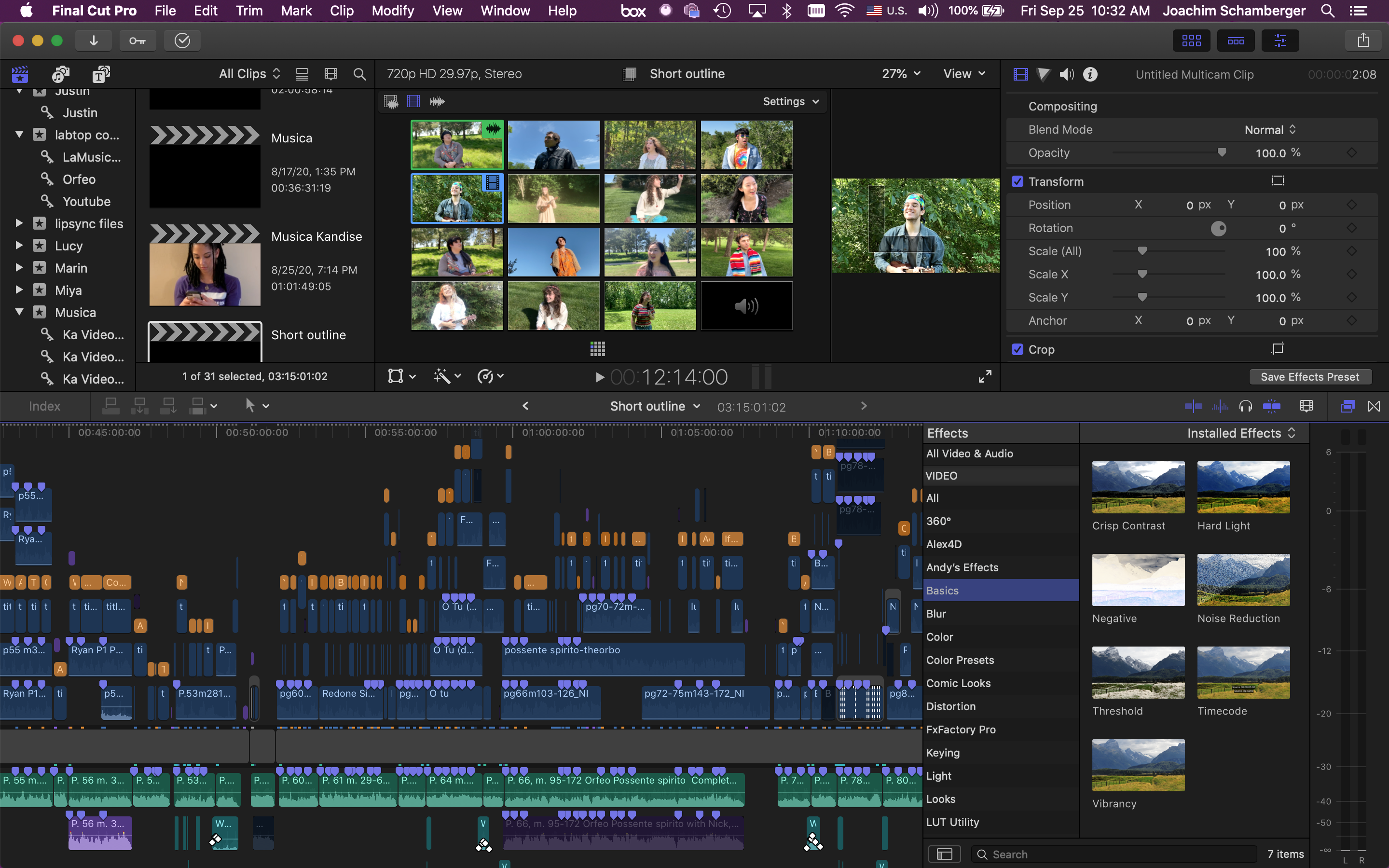

Schamberger originally thought he would get most of the film editing done by the close of the spring quarter at the beginning of June. “Then, as we started going through it,” he said, “and planning everything, I realized that timeline was absolutely ridiculous for what we had in mind and for how it turned out.” The last film clips trickled in at the end of July, and he since has been at work on the editing using Final Cut Pro X.

Whatever the participating students lost in having to work via the Internet and to forgo a live performance, the faculty members said, they gained in other kinds of knowledge, like audio and film production and understanding the precision that such an undertaking requires. Orfeo Remote also provides the participants a lasting record of their accomplishments and brings visibility to the Northwestern Opera Theater in a distinctive way.

At the same time, the film, with its regimen of meetings, coachings, and recordings, gave everyone what Alltop called a “backbone of certainty” during a time of uncertainty, something for which soprano Kandise LeBlanc was grateful.

“Having this opera production exist in any way, shape, or form,” said the recently graduated student, who portrayed La Musica, “was really beneficial to me as a student but also as a person. It was really great to have that sense of grounding and quasi-normalcy in a really unprecedented time.”

Kyle MacMillan served as the classical music critic for the Denver Post from 2000 through 2011. He is now a freelance journalist in Chicago, where he contributes regularly to the Chicago Sun-Times and Modern Luxury and writes for such national publications as the Wall Street Journal, Opera News, Chamber Music, and Early Music America.