by Tamara Bernstein

Published January 28, 2019

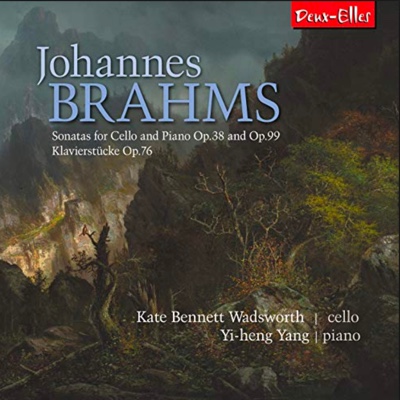

Brahms: Sonatas for Pianoforte and Cello, Op. 38 and Op. 99; Klavierstücke, Op. 76 (selections)

Yi-heng Yang, Streicher piano; Kate Bennett Wadsworth, cello

Deux-Elles DXL 1181

Yi-heng Yang and Kate Bennett Wadsworth are not the first modern musicians to record Brahms’ Cello Sonatas on period instruments — in this case an 1875 Streicher piano and a gut-strung cello played without endpin. But they are the first to do so while attempting to revive late 19th-century performance practice. This is territory on which angels might fear to tread: It means embracing practices that are utterly taboo today — notably, the rhythmic elasticity that in Brahms’ day was “as fundamental to good phrasing as the subtle inflection of dynamics and tone colours that we still use today,” as Wadsworth writes in the CD booklet.

For string players, it also means, among other things, developing instincts for 19th-century fingerings, which “incorporate a complex language of audible shifting, in which sliding and left-hand articulation take on a significance parallel to vowels and consonants in speaking or singing,” according to Wadsworth, and that also characterized opera singing and stage acting at the time. The pianist, meanwhile, must become fluent in the nuanced language of rolled chords without feeling like Liberace.

Wadsworth, however, has been researching 19th-century practices for years, alongside her career as a superb baroque cellist. And she and Yang have forged a deep musical bond over decades. Against all odds, the results are sublime: brave, astonishingly eloquent performances that glow with ardor and depth, and sound fresh off the composer’s desk.

The warm, transparent sound of the Streicher frees the cello from having to shout to be heard, and Wadsworth makes the most of it. With a handful of tiny “brushstrokes” — a tug of the musical line here; a touch of inégale or over-dotting there; a fleeting holding of musical breath; a gestural flurry that makes sense of a complex slur; a heart-piercing stab of vibrato, or a sudden urging forward — she brings to life every detail of the score and conjures protagonists about whom one immediately cares deeply.

It’s this vivid appeal to the imagination that ultimately seals the success of this adventure in HIP. That, and the artists’ thrilling command of musical time on every structural level and the touching emotional vulnerability they bring out in the music. In the opening of Op. 99, the cello comes across as brave but not cocksure, thanks to the quivering vulnerability imparted by Yang’s tremolos and the subtle instability Wadsworth creates by avoiding metrical certainty. Who, you suddenly wonder, has the strong downbeats here?

In the second movement, the cello’s opening pizzicati have none of their usual self-importance: Instead, they tiptoe hopefully alongside the piano, wobbling rather endearingly out of strict rhythm. The third movement is likewise more ardent than swashbuckling. The fugal finale of Op. 38, so often turned into an exercise in pompousness, here is a joyous tussle between discipline and wildness that ends in a headlong, electrifying rush to the finish line.

The care Wadsworth and Yang lavish on transitions is particularly rewarding, as they stretch time to navigate crucial harmonic and rhetorical turns or to let the music catch its breath after earlier excitements. Wadsworth’s vast palette of bow speeds enables her to bring time to the brink of standstill, her scarcely-moving bow whispering on the C string like an actor unsure whether he has the strength, or will, to draw another breath. At the same time, her sense of musical gesture and line has the strength and grace of a wild animal: Her melodies soar, not like a rocket, but like an eagle, responding to every turn of harmony and thought the way the bird responds to changing currents of air.

In five pieces from Brahms’ Klavierstücke, Op. 76, the singer-like qualities of piano and pianist take center stage, and the pieces come into their own as songs without words. Yang’s take on the Capriccio in B Minor, Op 76, No. 2, as a grotesque did not convince this listener and is unlikely to supplant Myra Hess’ witty, graceful account from 1928. But that’s the only disappointment on a magnificent, moving disc.

Tamara Bernstein has been a classical music critic for The Globe and Mail and The National Post (Canada) and has created numerous radio documentaries and features for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Since 2001, she has been artistic director of Summer Music in the Garden, the free, outdoor concerts held in the Toronto Music Garden.