by

Published April 22, 2019

(Photo courtesy of the Barcelona Museu de la Música)

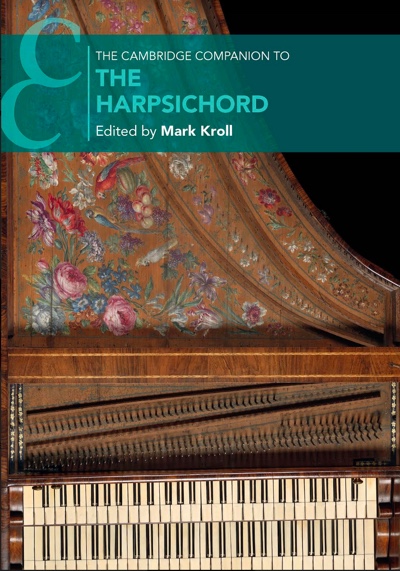

The Cambridge Companion to the Harpsichord. Edited by Mark Kroll. Cambridge University Press, 2019. 388 pages.

By Charlotte Mattax Moersch

To my delight, this Cambridge Companion inspired anew my love of the harpsichord. For this monumental book, Mark Kroll has put together a distinguished ensemble of experts who bring impeccable scholarship, imagination, and sensibility to their respective chapters. Approachable and comprehensive, this guide teaches us about the harpsichord’s history and construction, role in chamber ensembles, tuning and temperament, and repertoire from nearly every national school.

John Koster’s history of the harpsichord is informative and thought-provoking. He links its development to composers and their repertoire, showing how changes in aesthetic spurred alterations in design. In his overview of tuning and temperament, Paul Poletti challenges misconceptions held by players today, pointing to the overuse of Vallotti and Kirnberger III, which were “too late to have had much relevance to the harpsichord.”

John Koster’s history of the harpsichord is informative and thought-provoking. He links its development to composers and their repertoire, showing how changes in aesthetic spurred alterations in design. In his overview of tuning and temperament, Paul Poletti challenges misconceptions held by players today, pointing to the overuse of Vallotti and Kirnberger III, which were “too late to have had much relevance to the harpsichord.”

In his two chapters on the virginalist repertoire and Southern German composers, Pieter Dirksen infuses his brilliant surveys with invaluable insights; he clarifies sources (a Froberger autograph came to light as recently as 2006) and provides probing analyses of pieces by Byrd and Froberger.

Andrew Woolley writes with elegance about harpsichord music composed in England between ca.1630 and 1780. He calls our attention to a number of high-quality works “worthy of revival,” ranging from Blow’s French-influenced “Chacone in Faut” (ca. 1690) to a “Handel-inspired” sonata by Kirckman (1780).

Ton Koopman focuses on oft-neglected composers from the Netherlands and Northern Germany. His excitement about their music is infectious. If Lustig’s inventive sonatas impart “a sense of joy in playing,” Fiocco’s sonatas represent a “culmination of eighteenth-century harpsichord music from the Southern Netherlands.” Especially valuable are his opinions on sources, editions, instruments, fingerings, ornaments, and temperament.

Kroll, EMA’s book editor, leads us on a whirlwind tour of French repertoire from Chambonnières to Royer, questioning misinterpretations by modern harpsichordists of principles such as inégalité. He rightly underscores the French use of rhetoric — the connection between clavecin music and text. Later in the book, he affords a fresh look at the role of the harpsichord in ensembles, giving a novel perspective on accompanied keyboard music.

Rebecca Cypess takes an imaginative approach to her chapter on Italy, using a rhetorical model to present information about instruments, texts, and genres. A perorazione looks to the twilight of the harpsichord in Italy.

Through court records, João Pedro D’Alvarenga documents harpsichord music in Portugal, from Coehlo’s contrapuntal tentos to Seixas’s virtuosic sonatas. Águeda Pedrero-Encabo explores the rich history of the harpsichord in Spain, tracing its development from the diferencias (variations) of Cabezón to the sonatas of Soler and de Nebra. Particularly helpful are the musical examples, which hint at the flavor of folk rhythms and guitar-like chords that perfume this repertoire.

Pedrero-Encabo and D’Alvarenga together investigate why Scarlatti scholarship remains on the fringe some 60 years after Ralph Kirkpatrick’s seminal monograph. Though mystery shrouds Scarlatti’s life, the authors present convincing evidence to support the suspicion that he was a spy. Recent studies are uncovering new avenues of research, among them an intriguing connection between Scarlatti and Rameau regarding hand crossing.

Marina Ritzarev paints a vivid picture of the harpsichord in Russian court life. Grounding her narrative in the socio-political context of the day, she proposes theories for why so few pieces remain, despite the lavish collections of harpsichords in St. Petersburg. She introduces some little-known Russian composers, among them Dmitry Bortniansky, whose sonatas imbue Viennese sonata-allegro form with Russian gestures.

A paucity of sources plagues the Nordic and Baltic countries as well. Although German émigrés dominated musical life in Scandinavia, Anna Maria McElwain has unearthed a number of Swedish harpsichord composers of merit.

Pedro Persone highlights the role of the harpsichord in the Colonial Spanish and Portuguese America, peppering his discussion with colorful anecdotes. It is surprising how many harpsichords existed in South America. The oldest surviving Ruckers, a virginal built in 1651, was found in Peru.

In “Bach, Handel, and the Harpsichord,” Robert Marshall constructs a captivating narrative about their instruments, approaches to playing and teaching, continuo styles, and music. Marshall offers some tantalizing suggestions, for example, that the similarities between some fugues of Handel and Bach are not mere coincidences.

Larry Palmer immerses us in the world of contemporary harpsichord music. In many cases, he has first-hand knowledge about the pieces (having interacted with the composers themselves), some of which he personally commissioned and debuted, making his beautifully written essay all the more compelling.

Each chapter stands on its own, thus I could read the book out of sequence, moving easily from Coehlo’s Flores de mvsica to Fischer’s Musicalishes Blumen-Büschlein. The still blossoming world of the harpsichord is made richer by this book.

Charlotte Mattax Moersch, Professor of Harpsichord and Musicology at the University of Illinois, has recorded solo harpsichord pieces of Noblet, Février, D’Anglebert, A-L Couperin, J.S., and W.F. Bach. Her latest CD, The Bach Legacy, will be released by Centaur Records in May.